Almost six months after our last visit – when we walked from Holywell Bay to St Ives – we found ourselves back on the train down to Cornwall.

It was late March: we had timed this trip to help us get ‘walking fit’ for our impending Channel Islands holiday.

This time our destination and base for the week was Penzance.

Starting from St Ives (of course), we planned to complete the northern Cornish coast, round Land’s End and, ideally, reach Penzance.

Once again we travelled on the 10:04 departure from London Paddington, though this time on a Friday morning.

The train didn’t seem too busy – we had a table to ourselves – and it ran to time, delivering us to the Penzance terminus shortly after 15:00. Unfortunately though, we couldn’t log in to GWR’s wifi, which made our five-hour journey seem even longer.

Our fellow passengers seemed comparatively nondescript, all rather reserved, apart from one rather shapely, glamorous lady, in bright blue leggings, with a big floppy hat and a continental accent, who struggled with the protocols, explaining to everyone that she had never before travelled on a train.

Next morning though, we’d both been pinged by the NHS Covid app, and it seems most likely that one of our fellow passengers on this service had been the source. Was it the glamour puss or one of the quieter passengers? We shall never know.

We decided on a flexible itinerary, so we could take advantage of fine weather, adjusting our walks to suit the difficulty of the terrain and the availability of bus stops nearby.

In the event, the weather was fine all week, though increasingly windy on the first two days. The ground was largely dry, but with frequent boggy patches.

The terrain was very mixed: we encountered several challenging sections, with some extended clambering over boulder-strewn paths, but these were interspersed with far smoother passages. After Mousehole, the run-in to Penzance is mostly pavement.

Unfortunately there were substantial gaps in the bus timetable, attributed to driver shortage, and this reduced our options considerably. On the other hand, every bus we wanted to catch arrived, and ran more or less to time.

We had to make unexpected allowances for our health: Tracy experienced cold symptoms on Saturday and Sunday especially, while I had similar symptoms on Monday, though less severe.

Our final itinerary fell out like this:

- Saturday: St Ives to Zennor (6.5m)

- Sunday: Zennor to Pendeen Watch (7.2m)

- Monday: Pendeen to Sennen Cove (9.1m)

- Tuesday: Sennen Cove to Penberth (7.5m)

- Wednesday: Penberth to Penzance (10.3m)

- Thursday: rest day, including a visit to St Michael’s Mount off Marazion (3.1m).

So a total of 43.7 miles, including some of the most beautiful parts of the entire coast path.

Penzance

We had booked our cottage, Rosevean, through Aspects Holidays, which had also supplied our base in St Ives.

This was located on Rosevean Road, just a few minutes’ walk from the railway and bus stations.

It might have been a tight squeeze for a larger party, but it suited the two of us very well. We paid £428 for the week, which seemed good value.

The house was equipped with everything we needed, though I was slightly disappointed that the bath, in the downstairs bathroom, was not quite full-sized. After each walk, only two of my aching limbs could be soaked simultaneously, and sharing was completely out of the question.

After unpacking we went for our customary ‘orientation walk’, checking out the fastest route to the bus station and taking a few photos of St Michael’s Mount over the sea wall.

Penzance itself was a pleasant surprise. It has a resident population of some 16,000, – rising to 21,000 with the inclusion of neighbouring Newlyn and Mousehole – but seems larger.

The first recorded reference to Penzance was in the Assize Roll of 1284 and, though small and distant, it prospered through the later medieval period and, subsequently, under the Tudors and Stuarts.

Indeed it continued to thrive in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, for there are numerous listed buildings from this period scattered through the Town. I particularly enjoyed the Egyptian House, an early Victorian tour de force in Egyptian Revival style.

The railway station opened in 1852, though a direct service from London Paddington was not introduced until fifteen years later, hearalding the rapid development of tourism.

Nowadays, though, there is substantial poverty here, not confined to the Treneere housing estate, one of the most socially deprived in England. It isn’t hard to spot the tell-tale signs of alcoholism and addiction.

But parts of Penzance are noticeably more affluent, especially the predominantly Victorian area surrounding Morrab Gardens, a delightful sub-tropical municipal park which opened in 1889.

We visited them on the morning of our final ‘rest day’, sitting awhile on a shady bench near the fountain before wending our way back through the town centre.

Earlier we had breakfasted at Zebra Crossings, a first-class café located opposite a crossing on the Morrab Road. It also hosts a large population of zebras inside. Our Cornish breakfasts were excellent, and we were bowled over by the care and attentive service provided by the ladies who worked there.

As is our custom, on our final evening, we treated ourselves to dinner at a local restaurant. On this occasion Tracy chose The Shore Restaurant, a cosy 14-cover seafood establishment owned by Chef Bruce Rennie.

Customers have to pay up-front for the meal – £90 per person in our case – and on the night for drinks. There is a taster menu comprising five mini-dishes, all fish-based, and a mini-dessert.

We declined the boozy option of a ‘flight’ of six wines, one to accompany each dish, opting instead to share a bottle alongside the main courses, with a final glass of Tokay for the dessert.

Mr Rennie chatted before each course about what it contained and where he’d sourced the ingredients. He seemed creative, driven and sincere, genuinely committed to using local produce, supporting local fishermen and suppliers.

Perhaps it’s my problem, but my finely-tuned ‘pretentiousness antenna’ was waggling just a little.

Earlier in the week, we’d tried out the Artist Residence on Chapel Street.

At the other end of the room, a man with a Yorkshire accent was endlessly extolling the virtues of Tresco, where he was travelling the next day. I felt quite sorry for the lone woman on the next table, who invariably bore the brunt.

And on our first night we bought some very nice fish and chips from Market Plaice.

Otherwise we cooked for ourselves, buying what we needed daily from the local Co-ops and Tesco Express.

Saturday: St Ives to Zennor

We were up and out in time to pick up the 08:45 17 bus to St Ives. As we climbed on, the driver was worried he might have a fault, but it was soon resolved and we had arrived at the Malakoff bus station by 09:30.

Last time we’d ‘officially’ finished down in the Harbour at low tide, but had later continued round to Porthmeor Beach.

We debated where we should restart, descending through the Town to the Harbour, then taking care to follow the official coast path route, via Porthgwidden Beach and St Ives Head.

Skirting Porthmeor Beach, we found the beginning of the path proper alongside Beach Road, advancing rapidly to Clodgy Point. ‘Clodgy’ is said to mean ‘sick house’ and there was, allegedly, a hospital or colony for lepers hereabouts.

Rounding the headland, the coast path signs mysteriously vanished, and we somehow found ourselves heading inland and back to St. Ives via Higher Burthallen.

Retracing our steps, we eventually found our way somewhere above Hellesveor Cliff.

We soon passed Hor Point, which housed a WW2 radar station, part of the so-called Chain Home Low system, destroyed in 1945. Before electric motors were installed, the mobile antennae were apparently powered by WAAFs pedalling wheel-less bicycles!

The ground became increasingly boggy beyond this point: at various stages we had to hop from one judiciously placed stone to another to avoid ankle-deep mud.

We encountered something called ‘The Merry Harvesters Stone Circle’ which is merely a modern replica, though in a striking position above Trevalgan Cliff, between Pen Enys and Carn Naun Points.

There is, apparently, a unique type of granite hereabouts, called Trevalganite.

We stopped for lunch above the River Cove, looking out on to The Carracks, a cluster of small rocky islands renowned for their colonies of grey seals, though we saw none at all.

By this stage the warm morning sun had all but disappeared, the brisk March wind grown increasingly chilly.

Rounding Mussel Point, we could see Zennor Head jutting into the sea ahead, beyond it the finger of Gurnards Head and the vague shape of Pendeen Head beyond that.

We saw Wicca Pool, where DH and Frieda Lawrence swam while staying at the Count House in High Tregwerthen. Here they were joined, albeit briefly, by Katherine Mansfield and John Middleton Murry, and Lawrence wrote most of Women in Love, before they were forced to leave, under suspicion of being German spies.

In February 2016, Lawrence wrote of Zennor, to Lady Ottoline Morrell, in fairly typical Lawrentian fashion:

‘When we came over the shoulder of the wild hill, above the sea, to Zennor, I felt we were coming into the Promised Land. I know there will be a new heaven and a new earth take place now: we have triumphed. I feel like a Columbus who can see a shadowy America before him: only this isn’t merely territory, it is a new continent of the soul.’

And, that same month, to Mansfield and Murry:

‘At Zennor one sees infinite Atlantic, all peacock-mingled colours, and the gorse is sunshine itself, already. But this cold wind is deadly.’

Feeling much the same, we continued alongside stony Tregerthen Beach, on to Tremedda Cliff and round Zennor Head, arriving eventually at the plaque on the cliff, high above Pendour Cove, which marks the donation of Zennor Head to the National Trust in 1953.

Here we encountered several people who had walked out from the village of Zennor, to which we now repaired.

Arriving there around 14:30, we took shelter from the stiffening wind in the porch of St Senara’s, Zennor’s parish church, after whom the village is named. Much of this dates from the Thirteenth to the Fifteenth Centuries, though it was partly rebuilt in the Nineteenth Century.

We didn’t look inside, so missed out on the Mermaid Chair. According to the Church’s website:

‘…the only remaining Mediaeval bench end carved over 500 years ago and linked to the legend of the chorister, Matthew Trewhella. It is said he was lured into the sea at Pendour Cove by the mermaid who came into the church to hear his beautiful singing.’

Instead, we made our way to a small but popular café, where I utterly failed to spot the cakes!

Afterwards we hurried to the bus stop, shivering there for some minutes before the 16A service came along. That took us to Carbis Bay, where we climbed aboard another 17 to reach Penzance.

A group of girls, apparently pissed, more than made themselves heard downstairs. One eventually persuaded the driver to pull over so she could urinate behind some bushes, we upstairs passengers averting our gazes to spare her modesty.

Sunday: Zennor to Pendeen Watch

Because of driver shortages the only way to reach Zennor was to catch the Atlantic Coaster. It took 90 minutes, including a 25 minute stop at the Malakoff in St Ives.

Arriving on schedule at 10:30, we returned swiftly to the Coast Path, just behind two couples, each dad carrying a small child on their backs. Flashback to the time I slipped on some wet slate carrying our (then) two year-old in the same fashion!

The path descended towards Pendour Cove, over a footbridge suspended above a waterfall. This is where Morveren, the mermaid, is reputed to live.

She has inspired many artists. There is a Barbara Hepworth sculpture called ‘Pendour’, a 1900 watercolour by John Reinhard Weguelin (1849-1927), poems by Vernon Watkins, Charles Causley and John Heath-Stubbs – and several folk songs besides.

The coastal scenery was beautiful in the mid-morning sun as we progressed along Carnelloe Cliff, out towards Carnelloe Long Rock and round Porthglaze Cove.

There was once a tin mine here and we passed a sign asserting that the landowner ‘accepts no responsibility whatsoever for any damage, injury or loss of life’.

There is further evidence of mining at Treen Cove and the remains of a pilchard fishery which back in 1870 employed 24 men and 10 boats.

There is also the site of Chapel Jane – which may date back to the Twelfth Century, or even earlier, and was probably used until the Sixteenth Century. The parishioners of Zennor made an annual pilgrimage here and held a feast until the early Nineteenth Century.

Beyond Treen Cove lies Gurnard’s Head, named after the ugly fish it supposedly resembles. The path crosses the neck of the headland, which contains the remains of Trereen Dinas, an Iron Age promontory fort.

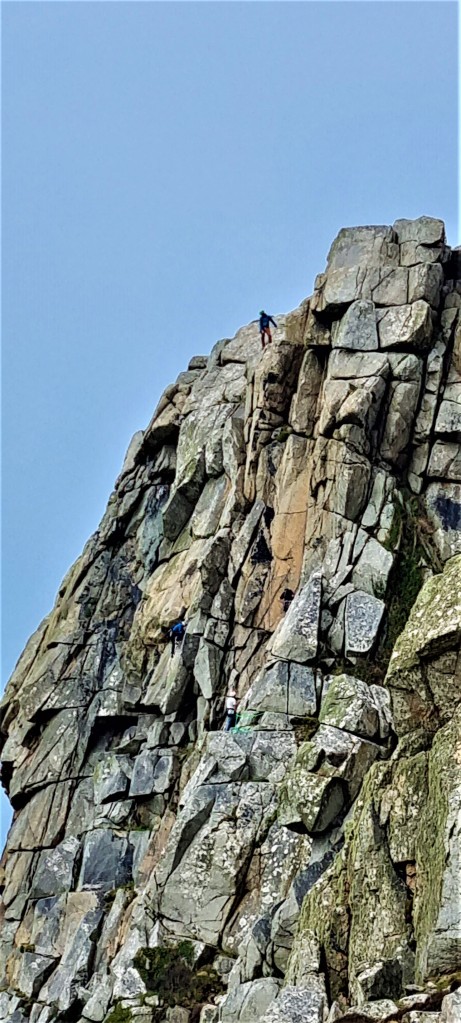

It continues upon Porthmeor Cliff and round Porthmeor Cove, then on to a series of cliffs, culminating in Bosigran, which hosts another Iron Age fort. Bosigran is also an important rock climbing centre.

We descended to ruins, most probably part of nearby Carn Galver mine, directly behind Porthmoina Cove. This was once productive, especially during the 1830s when a 60-foot water wheel was constructed, though ultimately declined owing to poor drainage.

Here we stopped for our lunchtime picnic, staring at the climbers crawling up the sheer rock faces hundreds of feet above, to our right. Behind us, a small group of awkward teenagers, presumably outward bounding, was also taking in the grandeur of the scenery.

On the other side we could see Bosigran Ridge, also known as Commando Ridge, used by WW2 commandos to train for cliff assaults. In 1943, the Commando Mountain Warfare Training Centre relocated to these parts, basing itself in St Ives. After the War, it was renamed the Commando Cliff Assault Centre.

Following lunch we headed in that direction, passing close to Morvah through a section pockmarked by mineshafts. Somewhere near here a small hoard of six Bronze Age gold bracelets was uncovered during quarrying in 1884. They are now in the British Museum.

Soon we could see the squat shape of Pendeen Lighthouse in the distance, although the weather was now deteriorating, just as it had the day before.

We skirted beautiful Portheras Cove where, owing to the wreckage of the coaster Alacrity, which foundered here in 1963, one is still advised not to walk with bare feet on the sand. In 1981, the Royal Engineers tried to dispose of the wreck by blowing it up. Most of the shards have since been removed but fresh pieces are still occasionally exposed.

Pendeen Lighthouse was built in 1900 and fully automated in 1995. We completed the surprisingly long walk round to the road heading inland before deciding to call it a day, given the deteriorating weather and our fatigue.

We had a stiff walk up to Pendeen itself, into the teeth of what had now become a gale, finally making it to the bus-stop opposite Costcutter a little after 16:00. Here we had a 20-minute wait for the 18 service, which soon deposited us back in Penzance.

Monday: Pendeen Watch to Sennen Cove

By Monday, Tracy was feeling rather better, but I was feeling rather worse!

We caught an early 18 bus back to Pendeen, then trekked back down to the coast in far better weather than the previous evening.

We passed a toad, crossing the road at a much more leisurely pace. We hoped he survived the car that sped over him shortly afterwards.

Picking up the coast path on Pendeen Old Cliff, we were soon in sight of the ruins of the Levant and Botallack Mines, the chimneys stark against the deepening blue of the morning sky.

There have been small mines here for centuries. The name ‘Levant Mine’ was current by the mid-Eighteenth Century and, in 1820, the Levant Mining Company was formed when 20 shareholders together invested £400. By 1840 it had already made a profit of £170,000.

At this point, Levant was employing some 550 men, women and children. They mined tin and copper ore and, as a by-product, manufactured arsenic (used as a dye, a pesticide and medicinally).

Women and girls were predominantly employed as ‘bal-maidens’ breaking down and sorting the ore once it had reached the surface.

The mine ran to a depth of about 600 metres and extended up to 2.5 kilometres under the sea. In 1857 a ‘man engine’ – a steam-driven system of moving ladders and platforms – was installed to carry miners down from the surface to the deepest shafts and back up again.

By 1883, the mine was worked in three 8-hour shifts, six days a week, some sixty men extracting the ore in 90-degree temperatures.

But on 20 October 1919, the man engine collapsed, killing 31 miners. It took five days to recover all the men marooned below and, after this, the deeper levels of the mine were abandoned.

The mine closed in 1930, when the price of tin collapsed. Since 1967 it has been owned by the National Trust.

The coast path passes directly through the ruins. We wandered along, reading the information panels and taking many photographs.

After a short interlude we were soon close to Botallack Mine, where the workings again extend out under the sea. It is famed for the Crowns engine houses, built in 1815 on the very edge of the cliffs – and the fact that parts of Poldark were filmed here.

The Prince and Princess of Wales visited in 1865 to open the new Boscawen diagonal shaft, 900m long and at its end, 550m under the sea. However, this mine soon became uneconomical and had closed by 1895.

Soon we had reached Kenidjack Castle, another Iron Age promontory fort, and could look across the bay to the mound of Cape Cornwall, crowned by its own chimney stack, built in 1894.

Capes are the points where two separate bodies of water meet and this is one of only two in the UK (the other being Cape Wrath).

Strangely, the mine site was purchased by H J Heinz (of baked beans fame) in 1987, as part of its centenary celebrations, but subsequently donated to the nation. Most of the Cape is now National Trust land.

We climbed up to the chimney stack, past St Helen’s Oratory, to enjoy the view. Then, the coast path seeming to require it, we went around the headland. In doing so we disturbed a small adder basking in the sun. Luckily I was at the front and cleared the way for Tracy, who hurdled the spot with the greatest alacrity!

The section immediately after Cape Cornwall is fairly lacklustre by comparison with what has gone before. We failed to notice Ballowall Barrow, a Bronze Age funeral mound, 22 metres in diameter, discovered underneath mine waste in 1878.

The quality picked up as we navigated inland to cross the lush Cot Valley, bisected by a stream and featuring a couple of donkeys grazing in idyllic surroundings.

On the other side we stopped for lunch, perched just above the beach, the twin peaks of the Brisons rising out of the sea in front of us.

For some reason, they are said to resemble ‘General de Gaulle in his bath’ and have been the cause of several shipwrecks.

To the west we could now see distinctly the distant Longships Lighthouse, which drew slowly closer during the remainder of our walk.

The weather remained glorious after lunch as we continued on past Gribba Point, Nanjulian Cliff and into the dunes to the rear of Whitesand Bay.

At some point on this stretch, Tracy slipped and fell heavily. She took a breather before rising to her feet and I was briefly worried that she’d hit her head. Thankfully she hadn’t.

A little later we realised that we might just make the connection with the 15:30 Atlantic Coaster – we had expected to finish later, and so have to kill time at the pub in Sennen Cove while waiting for the next bus, over three hours later!

Although the beach looked beautiful in the mid-afternoon sun, we put on a spurt and made it into Sennen Cove with minutes to spare.

I asked a rather vague man if he could tell us where we could find the bus stop. He had no idea but we soon realised it was just a little way along the front – he must have walked past it a minute before!

The bus was turning as we arrived and we jumped aboard with some relief. Despite Tracy’s bruises and my snuffles, it had been a truly amazing day, perhaps the most spectacular to this point.

Tuesday: Sennen Cove to Penberth Cove

It was another early start, as we caught the 08:30 Atlantic Coaster to Sennen Cove. This involved a longish wait at Land’s End, where we would return later that morning.

Another couple on the bus were looking for an open café in Sennen Cove but, as we set out, it seemed they might have rather a long wait.

After passing through the last houses we were soon climbing up to the Old Coastguard Lookout on Mayon Cliff.

There has been a coastguard station here since 1812, but this granite construction dates from either 1891 (what the National Trust says online) or 1912 (what the plaque on the building itself says).

It closed in 1953, but the Trust restored it, in either 1997 or 1998, depending which source you prefer.

We could already see the cluster of rather unprepossessing buildings at Land’s End, just ahead of us, as we passed the remains of Maen Castle, an Iron Age cliff castle overlooking Gamper Bay.

Another plaque informed us that the RMS Mulheim, a German cargo ship, was wrecked here in March 2003, after the chief officer fell unconscious while on watch. What’s left of the wreck still lies here and is considered dangerous.

As we crossed the heath we indulged in a little idle bird-watching, looking out for newly-arrived migrants who had only just made land.

We passed the First and Last House, opposite Dr Syntax’s Head, built in the Nineteenth Century and long operated as a café and souvenir shop.

The headland is thought to resemble the hero of The Three Tours of Dr Syntax – a comic poem published by William Combe between 1809 and 1821 – as illustrated by contemporary caricaturist Thomas Rowlandson.

Over at the Land’s End complex, the guy snapping punters posing below the signpost was doing a roaring trade. We decided not to bother, but did manage our own celebratory selfie, with the Longships Lighthouse in the background.

We admired the impressive Enys Dodnan arch. But, only when passing Greeb Farm, did we begin to realise the significance of ‘making the turn’: henceforth, we would be travelling in an easterly direction, towards home.

We passed a sequence of narrow inlets or ‘zawns’, interspersed between headlands, before arriving adjacent to Nanjizal Beach and its waterfall.

On the way down we chatted with a couple who told us there was a seal on the beach. We didn’t want to frighten him by approaching too closely and, for a long time, we couldn’t see him. Then we spotted him lying beneath the foot of the cliff: he didn’t look too well.

Climbing again, up to Higher Bosistow Cliff, we noticed the site of another small promontory fort on the headland called Carn Les Boel. Then it was on past several small headlands to reach the Lookout Station at Gwennap Head.

Shortly afterwards, we remarked the red and black cones standing on the cliff. They were first established here in 1821 and align with a buoy, out to sea, which marks the position of the Runnel Stone, cause of many shipwrecks.

Between 1880 and 1923 at least 30 steamships were wrecked, stranded or sunk there, the last being the SS City of Westminster, a 6,000 ton cargo vessel which decapitated the reef making it slightly less dangerous.

We passed the very photogenic Porthgwarra Beach Café, but decided they would be unlikely to let us eat our picnic lunch in their walled garden – and there were no other comfortable stopping places nearby.

So we went on to St Levan’s Well, where we lunched perching precariously on a rocky ledge a few metres above the beach.

The area around the well was roped off for excavation. There are also the remains of a chapel and a small hermit’s cell cut into the cliff face below. These may date as far back as the Seventh or Eighth Century but, as the informative notice board reminded us:

‘…there are no scientifically dated Cornish chapels pre-dating the Norman period’.

On leaving the area, we also noticed a small memorial:

‘Near to this place on 7th February 2016, RSPCA Inspector Mike Reid tragically lost his life whilst trying to assist a number of seabirds in distress during Storm Imogen.’

Ahead of us now we could see the sweep of Porthcurno Beach.

The path took us directly behind the Minack Theatre, which seems to be much more of a tourist trap than when I last passed through, roughly 25 years ago.

Continuing along Treen Cliff, we passed Treryn Dinas, location of another promontory fort, but were unable satisfactorily to identify Logan Rock, a so-called rocking stone, once infamously dislodged by a bunch of sailors from HMS Nimble, led by Oliver Goldsmith’s nephew, Hugh Goldsmith.

The local residents demanded that the Admiralty replace their tourist attraction, and they eventually complied, though it took over 60 men and cost £130.

We were surprised to find – immediately in our path and somewhere above Pedn Vounder Beach – a couple of Dartmoor ponies busy chomping through the undergrowth.

Rounding Cribba Head, we descended to Penberth Cove, once another pilchard fishing centre. A few fishermen still catch lobster and crab from here. The Nineteenth Century capstan has been restored and stands just above the beach.

As on the day before, we had arrived rather earlier than anticipated, but this time we had three-quarters of an hour to kill before we walked up through Penberth Village to pick up the Atlantic Coaster near Treen.

It was getting chilly and the breeze had stiffened again. We briefly considered walking on, but decided against since the next bus connection wasn’t until Lamorna, several miles distant.

Wednesday: Penberth Cove to Penzance

The Atlantic Coaster deposited us at Treen bus shelter bright and early next morning. It was shirtsleeve weather again.

The first section above Penberth was pleasant though largely featureless, apart from a small waterfall at Porthguarnon. We passed the handful of buildings at St Loy’s Cove and went on above Boscawen Cliff.

Somewhere hereabouts Tracy was just gearing up for a call of nature when a young man appeared carrying a shopping bag.

He told us he was walking some of the path and sleeping rough. He’d had a disturbed night, having discovered that ‘rodents’ were mauling his food supply.

Before long we could see the top of Tater-du Lighthouse peeping above the cliff. This is Cornwall’s newest lighthouse, built in 1965 following the loss of a Spanish coaster, the Juan Ferrer, on Boscawen Point.

We had a much clearer view from the other side, as we continued along Rosemodress Cliff before heading down towards the quay at Lamorna Cove.

There’s a solitary celtic cross up here that commemorates the death of David Wordsworth Watson, a 23 year-old Cambridge undergraduate who fell over the cliff in 1873 while walking with his sister and a friend.

At Lamorna we found a very pleasant bench for lunch, just a few metres away from a pair of watercolour artists who had set up their easels together.

There was once an artists’ colony here, led by S. J. ‘Lamorna’ Birch, who first arrived in 1908.

In June 1937, Dylan Thomas stayed here at Oriental Cottage with Caitlin Manamara, his wife to be. He wrote to his parents of:

‘A beautiful little place full of good fishermen and indifferent visitors…the haunt unfortunately of aged RAs and presidents of West Country Poets’ Rambling Clubs.’

Above Lamorna the path is strewn with hundreds of huge boulders that have to be clambered over, one after the other.

Imagine our surprise, then, to encounter a man hauling an electric bike in the opposite direction. He claimed to be engaged on a 50km ride, but I’m not sure he’d expected cyclo-cross!

We passed a board marking Kemyel Crease Nature Reserve, which is bifurcated by the coast path.

Soon we were level with Point Spaniard, reputedly the place where a 400-strong Spanish raiding party came ashore in August 1595 (though records also refer to them landing in Mount’s Bay).

Most of the militia defending the coastline ran away, leaving the Spanish to attack Mousehole, Newlyn and finally Penzance, where they burned down more than 400 houses and sank three ships in the harbour.

Arriving into Mousehole, the tide out in its tiny harbour, I recognised the Ship Inn where I’d stayed with my late wife Kate back in the 1990s – and which Dylan Thomas had also frequented during his honeymoon in Summer 1937.

We were looking for a suitable stop and eventually lighted upon the Rockpool Café where we enjoyed superb cream teas.

As we scoffed, a visiting songwriter offered one of his songs to other customers behind us, while a would-be David Bailey repeatedly snapped his long-suffering girlfriend on the rocky foreshore in front.

Soon afterwards we came upon the old Penlee Lifeboat Station, and the memorial garden commemorating the eight crew members who lost their lives on 19 December 1981 while trying to rescue those aboard the Union Star.

From here, the coast path follows the road into Newlyn, adjacent to and indistinguishable from Penzance, which boasts the largest fishing port in England.

Newlyn also had its own artists’ colony, the Newlyn School, first established in the 1880s.

The route passes round the Harbour, where in 1620 the Mayflower docked for supplies, before heading out across the Atlantic.

It crosses an area called Wherry Town and then on towards Penzance Harbour, skirting an art deco lido built in 1935. Before too long we were back at the Bus Station, where each of our daily trips had begun.

Thursday: Penzance to Marazion

After spending our final morning in Penzance we set off in the afternoon to trudge the three miles or so to Marazion, where we had booked tickets to visit St Michael’s Mount. It was a warm and beautiful afternoon.

Setting out across the exposed causeway, we climbed up to the castle, now managed by the National Trust in conjunction with the St Aubyn family, which has been here since 1659.

There might have been a monastery here as early as the Eighth Century…

During Richard I’s reign the Mount was captured by knights loyal to the future King John. Later, during the Wars of the Roses, it was seized by the Earl of Oxford and subsequently besieged by Edward IV, until Oxford surrendered.

Milton used it as the setting for the finale of his poem ‘Lycidas’, written in 1637 and, during the Civil War, it was held by the Royalists before Parliamentarian Colonel John St Aubyn was appointed its Captain in 1647. He bought it from its previous owners twelve years later.

In 1727 the harbour was significantly improved and the Mount became a port in its own right. By the 1820s the village below the Castle had over 200 inhabitants and there were three pubs for thirsty sailors. But, within half a century, the harbours on the mainland re-established their ascendancy and the village went into decline.

We wandered around for a while, taking photographs, before heading back towards Penzance across the sand, only veering inland for cooling ice creams.

These we consumed on a bench, watching a flypast by Hawk jets, circling the Cornish coast to commemorate their retirement from RAF Culdrose.

Next morning we completed our packing and tidied the cottage before walking down to climb aboard our train for the return journey.

It was largely uneventful, apart from more wifi problems.

But, a couple of days later, Tracy tested Covid-positive. Fortunately she endured only mild symptoms. Almost miraculously I stayed negative. Then the washing machine refused to empty itself.

It wasn’t so great to be home.

TD

June 2022

Beautiful captures! Great sharing! Thanks!

LikeLike