.

I have amended this post to reflect a more recent and much more likely hypothesis about Arthur Herbert’s parentage.

This is the colourful story of Arthur Herbert Dracup, also known as Herbert Dracup, who acquired an intimate and extended knowledge of prisons and penal servitude during the late Victorian and early Edwardian eras.

His birth is veiled in some mystery.

We know that an Arthur Herbert Dracup was born in Bradford in the final quarter of 1862. Family trees customarily but incorrectly attribute him to John Dracup (1834-76) and his wife Betty Dracup, nee Andrew (1832-1909).

There is firmer evidence that a Herbert Dracup was born to John and Betty in the second quarter of 1866, the record confirming the mother’s maiden name as Andrew.

Most family trees combine these two identities into a single individual, though the evidence shows they were two separate individuals.

As we shall see, Arthur Herbert’s subsequent court and criminal records utilise both names and a variety of birth dates. But there would have been advantage to a career criminal in having two identities: Arthur Herbert might deliberately have used his contemporary’s name as an alias.

.

.

Herbert Dracup’s family

John Dracup was directly descended from Nathaniel Dracup, the prominent early Methodist, via his eldest son John (1752-1824), grandson John (1778-1841) and great-grandson Joseph (1808-1866).

The 1841 census describes John’s father Joseph as a joiner living on Great Horton High Street. In 1851 he had become a machine-maker occupying 87 Great Horton High Street and in 1861 a carpenter living at 44 Hollingwood Lane.

The machines he constructed were almost certainly wooden looms and associated mill equipment, so these three roles were overlapping. (Joiners typically constructed pieces in the workshop and carpenters fitted them on site.)

John was Joseph’s third child and eldest son, born on 26 October 1834 and baptised on 24 July 1835. Joseph had three more sons by his first wife, Priscilla Holroyd (1805-44) before marrying his second, Sarah Barker (b.1801), in 1851.

By 1851, John, then aged 16, was apprenticed to a machine maker, most probably his father. He married Betty Andrew, on 2 February 1856 at the age of 21. Both parties signed their names, showing they were literate.

Betty was a blacksmith’s daughter, two years older than John. She was employed as a drawer, organising threads by taking them from different bobbins to form the requisite pattern.

The job often suited the infirm, disabled or pregnant, as it could be done sitting down. Betty was six months pregnant at the time of her marriage.

John is described simply as ‘mechanic’.

.

The 1861 Census finds the family living at 20 Norcroft Brow in Little Horton – now part of the Bradford University complex. John was employed as a joiner in a machine shop.

The 1871 Census gave his address as 9 Morpeth Street, Little Horton, and he was now described as a ‘mechanic machiner’.

My family tree includes the following children, in order of birth:

- George Dracup (b.1856); living at home until he married Hannah White in 1886.

- Joseph Dracup (b.1859); living at home until he married Emmeline Robinson in 1880.

- Sarah Ann Dracup (b.1861); living at home until she married John Holmes Thornton in 1882.

- Priscilla Dracup (b.1863); living at home until she married Henry Samuel Setterington in 1890.

- Herbert Dracup (b.1866); living at home until his death, unmarried, in 1896 .

- Daniel (Dan) Dracup (b.1869); living at home until he emigrated to the United States in 1885, marrying Grace Waddington in 1890.

- John Dracup (b.1871); living at home until his marriage to Emily Metcalfe in 1895.

- Clara Dracup (b.1874); living at home until her marriage to John Farnell in 1894 and subsequent emigration to the United States.

So this Herbert Dracup was born in the spring of 1866 and died on April 2, 1896, at the age of 29. He worked as a worsted spinner and then as a woolcomber. He is buried in Scholemoor Cemetery, Bradford.

His father had John died in 1876, at the age of just 41, leaving charge of the household to his widow Betty. By 1901 all her remaining children had left home and she was boarding with the Thorntons – her daughter Sarah Anne and son-in-law John. She died, aged 77, in 1909.

Arthur Herbert Dracup’s family

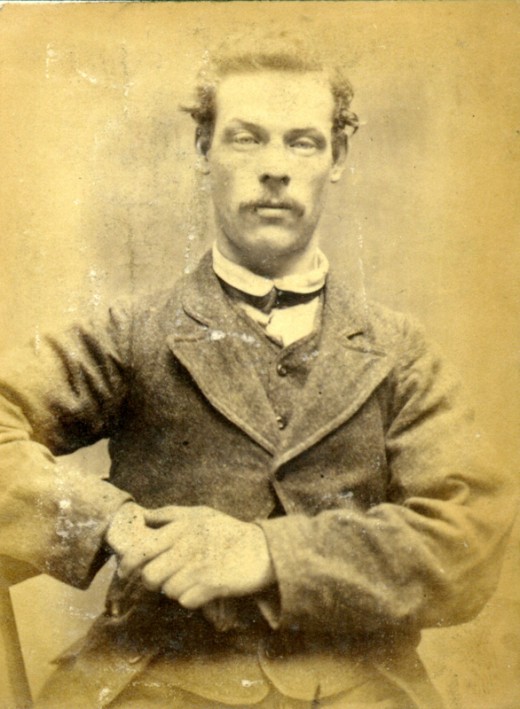

Arthur Herbert was born three years before Herbert, in the final quarter of 1862. We know from his marriage record, which cites no father, that he was illegitimate.

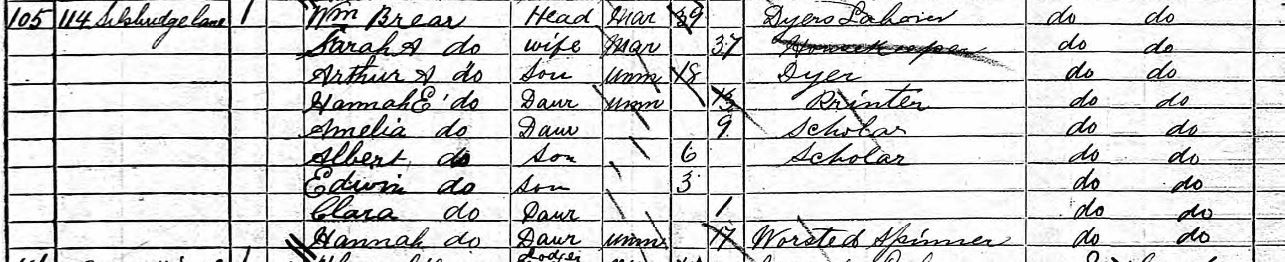

We also know, from later newspaper reports of his criminal activity, that he had a half-brother called Edwin Ernest Brear.

Edwin was born on 20 April 1877 to William Brear, a blacksmith living at 96 Silsbridge Lane, Manningham and his wife Sarah Ann, nee Dracup.

Sarah Ann had been born in the summer of 1843 to Abraham Dracup (1805-1872) and Hannah, nee Robertshaw (1812-1892). Abraham was a clogger, part of a Dracup clogging dynasty in Bradford.

But Sarah Ann didn’t marry William Brear until February 1863, some three months after Arthur Herbert’s birth, so he was strictly illegitimate.

We don’t know whether William was actually the father. He seemed at first willing to call his son by the surname Brear but it is clear that, by the time of Arthur Herbert’s marriage in 1896, he was unwilling to acknowledge paternity.

Sarah Ann was also descended from Nathaniel Dracup, but via a different son – Thomas (1760-1817) – so she was a relatively distant cousin of Herbert’s father.

The 1871 Census shows that William and Sarah Ann Brear had living with them a son called Arthur H Brear, aged 8. This is Arthur Herbert Dracup.

.

.

He was still part of the family at the time of the 1881 Census, taken in early April that year, though his name was mistakenly transcribed as ‘Arthur A Brear’.

Now 18, he was employed as a dyer. William Brear is no longer a blacksmith, having been reduced to the job of dyers’ labourer. The family live at 114 Silsbridge Lane, having moved a little further along the same road.

.

.

Criminal and court records from just six months later – 29 October 1881 – describe Arthur Herbert as an 18 year-old dyer from Silsbridge Lane.

Confusingly, the 1891 Census called him Herbert Dracup, but says he was born in 1864, has been employed as a cloth dyer, but is presently an inmate of Her Majesty’s Convict Prison, Portsmouth.

.

.

So Arthur Herbert and Herbert were entirely separate people, only distantly related. Arthur Herbert was born to Sarah Ann Dracup shortly before her marriage to William Brear, and he lived in Brear’s household throughout his childhood, until his first incarceration.

.

.

Arthur’s Early Criminal Career (1881-1895)

By using newspaper, court and prison records I have reconstructed Arthur Herbert’s complete criminal career. He was extremely active throughout the 1880s, almost up until his marriage.

.

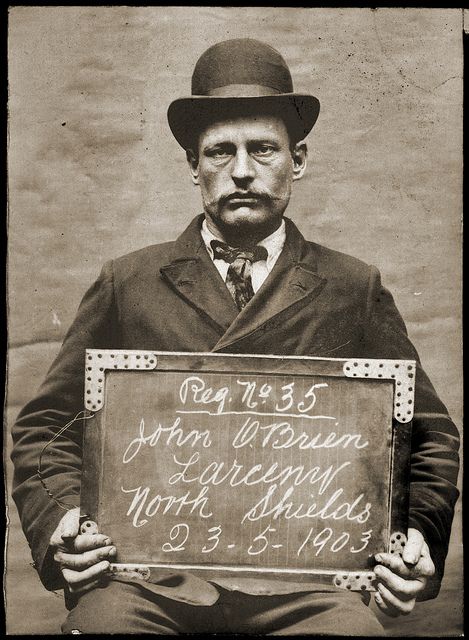

29 October 1881

Arthur’s first known court appearance was before the Bradford Borough Police Court, which was hearing ‘petty offences by lads’. He was just 18.

He was described as a dyer living in Silsbridge Lane and charged with stealing two wooden pipes, valued at 1s 6d, from a tobacconist in Ivegate, Mrs Emma Keighley.

The 1881 census shows that Emma Keighley was a 37 year-old widow, living above her shop at 20 Ivegate with her sister, her two young children and a servant.

She alleged that Arthur visited her shop at around 3.30pm the previous afternoon, asking to be shown some tobacco pouches. While her assistant went to find the pouches, Arthur picked up the two pipes and placed them in his pocket.

When confronted he denied the theft, but was arrested by PC Sheriff. At the Court next morning he pleaded guilty and was sentenced to one month’s imprisonment with hard labour.

.

2 June 1882

Arthur’s offence looks to be ‘gaming’. Most forms of gambling were prohibited at this time, under the terms of the 1845 Gaming Act and the 1853 Betting Act, which banned betting houses.

He was sentenced to seven days’ imprisonment in Wakefield Prison and, despite the theft of pipes a year earlier, was said to have no previous offences.

Wakefield prison was originally established as the West Riding House of Correction and had been rebuilt in 1847, with 732 new cells, before joining the national prison service in 1874. By this period, some 8,000 to 9,000 prisoners were admitted each year. Each cell contained a hammock, a stool, a small round table and gas lighting.

.

.

There is a first description: Arthur can read, was born in Bradford and professes to belong to the Church of England. He is said to be 17 years old (suggesting he was born in late 1864 or early 1865) though he is actually 19.

He is short – just 5 feet and three-quarters of an inch, with dark brown hair. He has two distinguishing features – a cut under his right eyebrow and a ‘blue dot’ between the thumb and first finger of his right hand.

Interestingly, a blue dot tattoo of this kind later became known as a ‘Borstal dot’, indicative that the wearer had been incarcerated in their youth.

.

9 December 1882

Arthur Dracup (20), a dyer of Silsbridge Lane and Reuben Trueman (22) of no fixed abode were charged with ‘sleeping on enclosed premises’. They had been found asleep in a stable on Silsbridge Lane at 01:00 that morning by PC Brazier. This was contrary to the Vagrancy Act of 1824.

Trueman clearly had nowhere else to go, but how and why Arthur placed himself in the same position is unclear. Presumably he was by now shut out of the family home.

They could not ‘give any satisfactory account of themselves’ so PC Brazier took them into custody. Trueman was sentenced to one month in gaol but, because Arthur was a previous offender, he received two months in gaol.

.

24 February 1883

This must have happened very shortly after his release from Arthur’s previous sentence. On this occasion he is said to be aged 21, a dyer of no fixed abode.

He was charged with stealing two sheets belonging to William Stewart on 14 February, with a value of 3s 6d. He had just taken lodgings for a single night in the lodging house owned by Mr Stewart in Sackville Street, and the sheets were found missing on his departure next morning. He had subsequently pawned them in Westgate.

The report adds that ‘he was apprehended at his father’s house in Silsbridge Lane’ (but clearly he is no longer living there). Responding to the charge, he said he stole the sheets so he could get something to eat. Given his previous convictions he was sentenced to three months with hard labour.

Under the 1865 Prison Act, hard labour was divided between Class 1 – often the dreaded treadwheel, or the crank, capstan, shot drill or stone breaking – and Class 2 – often entailing the prisoner undertaking his own job.

After 1877, no more than the first month of a sentence could be taken up with Class 1 hard labour. Prisoners were also separated and had to sleep on a plank bed without a mattress. Class 1 hard labour was abolished in 1898, though separation and plank beds were retained.

It is probable that Arthur was set to work as a dyer, though a Parliamentary speech from 1872 complains that some two-thirds of the population of Wakefield Prison were employed in mat-making!

.

.

10 October 1884

Some 18 months later, Arthur was convicted of stealing one pair of trousers and one pair of boots, valued at 15 shillings, from Mary Wilkinson in Bradford on 26 August.

He was described as a 22 year-old dyer with two identities – ‘Herbert Dracup alias Arthur Herbert Dracup’.

He was taken into custody on 9 September and tried at Bradford on 10 October before judge Gainsford Bruce QC. He pled guilty to a charge of ‘larceny after a previous conviction for felony’ and was sentenced to nine months in Leeds Prison and two years’ police supervision.

The proceedings were briefly reported in several local papers.

.

8 January 1886

Arthur was in trouble once again little over a year later. On Christmas Eve 1885 he was convicted of stealing a shirt, so most likely spent the festive period in police custody.

The brief newspaper coverage reveals that the shirt was actually stolen on 23 December from one Thomas Duxbury.

The case was heard at the Bradford Borough court sessions on 8 January 1886. The sentence was one year in gaol with hard labour. Four previous convictions were noted.

The physical description suggests he has grown slightly, to five feet one and a half inches. The cut under his right eyebrow is mentioned, but not the blue dot on his hand. His age is given as 22.

.

6 November 1888

Arthur was taken into custody once more, this time for stealing a pair of boots belonging to Edward Fitzsimmons in Bradford on 22 October 1888 and also stealing ’2 wood-turners’ chisels, 12 screwdrivers, and one pair of plyers, property of George Overend at Bradford’ within the previous two months.

Fitzsimmons was a 29 year-old tailor living with his wife and two step-children in the North Wing area of Bradford. Overend was a 23 year-old wood-turner living with his wife and two children at 11 Wigan Street

Arthur was taken into custody on 6 November and tried at the West Riding Assizes in Leeds before Sir Charles Edward Pollock. He was described as a dyer, aged 26.

Once again he pled guilty, this time ‘on two indictments after previous convictions of felony’. He was sentenced, comparatively leniently, to prison and hard labour for 8 months, this time at HM Prison Leeds.

This was Armley prison, built in 1847 at a cost of £43,000, inspired by the architecture of Windsor Castle, and comprising four radial wings, each with three landings. There were 480 cells, with 30 more added in 1857.

In 1882 it was purchased from Leeds Corporation for £9,000 and became part of the National Prison Service. The entrance has Grade 2 listed status.

In 1888 4,575 prisoners were admitted, a daily average of 419 prisoners. They were subjected to the silent system, not being allowed to communicate with each other. Labour was mostly picking oakum or making matting, though tradesmen could continue their trades and even carry out work for those outside.

.

.

There is a parallel entry in an 1889 directory of persistent offenders, recording Arthur’s release from Leeds on 7 August 1889.

This correctly recorded his year of birth as 1862, describing him as having a fresh complexion with dark brown hair and brown eyes, five feet one inch tall, of proportionate build and with an oval face. The blue dot is now his only distinguishing mark.

.

3 January 1890

As the decade turned, the authorities finally lost patience with Arthur. The record summarises his previous offences, showing that he has now been convicted three times of vagrancy and had also been discharged once for stealing turnips.

On this occasion he was convicted of stealing a black cloth jacket, valued at 5s and belonging to Edward Caygill, in Bradford on 8 October 1889. Caygill was a 20 year-old engine cleaner living with his uncle, a railway inspector, and family at 178 Undercliffe Street.

Arthur was taken into custody on 21 October but not tried until 3 January, once more before Gainsford Bruce QC.

As usual he pled guilty, on this occasion to larceny after a previous conviction for felony. But this time he was convicted to be kept in penal servitude for five years, and then to be subject to police supervision for five more years.

As we know from the 1891 Census, he was sent on this occasion to the convict prison at Portsmouth. A convict would previously have been transported but, by this time, would serve his sentence in a Government prison.

Portsmouth had been opened in 1852 as a public works prison, to replace the hulks which were formerly located in the harbour.

It had capacity for over 1,000 prisoners in two parallel four-storey wings. Further accommodation was added by 1870. The convicts worked on dockyard construction and as dockyard labourers, but the prison was closed on completion of the dockyard and the last prisoners left in July 1894.

Arthur spent four years at Portsmouth, until discharged on 26 February 1894 as an habitual criminal, his declared destination being 37 St Michael Road, Bradford – the address given on his marriage record two years later. His five years of police supervision began on 3 January 1895, so was due to end at the turn of the century.

We know from the 1894 Parliamentary Register that 37 St Michael’s Road was owned at this time by Robert Albert Knights.

.

.

9 September 1895

Arthur was once again convicted on 14 October 1895, just ten months into his supervision period. This time he was in Huddersfield, accused of stealing 13 shillings as a bailee.

The indictment, which is preserved, says that, at the time of the offence, Arthur was bailee of 13 shillings belonging to David Garside and, on 5 September, he stole that sum. The names of the witnesses are Ellen Garside, Henry Kaye, Thomas Hughes and George Collins.

An article in the Huddersfield Chronicle reveals a little more of the circumstances. Arthur had been lodging at Garside’s house at Cliffe End Fold, Longwood, Huddersfield since 26 August. Perhaps he was in Huddersfield because his wife-to-be, Sarah Ann Smith, was located there.

On 5 September, Garside gave him twelve shillings to pay as rent to Henry Kaye of the Huddersfield Equitable Building Society and a further shilling for his expenses.

He said he would return within an hour or two but did not do so. Kaye testified that he was agent for the owner of the property, one Henry Siswick, who was in America.

Arthur was arrested on 8 September by PC Hughes:

‘Prisoner said he should plead guilty to the charge, that he had had a lot of trouble, and when he got the money he thought “Now’s my time. I’m off.”

The case was heard at the Wakefield sessions on 14 October 1895. Arthur again pleaded guilty and was sentenced to six months’ imprisonment with hard labour.

His year of birth is given as 1861, his eyes are now described as hazel and, in addition to his blue dot, there are freckles on his neck and arms.

.

Arthur Herbert Marries, Sires and Loses a Family

Shortly after Herbert the woolcomber died, between April and June 1896, Arthur Herbert the criminal married, the ceremony taking place on 3 August that year.

The marriage record reveals how he has begun to adjust his name and age.

.

.

His age was given as 27, consistent with birth in 1868 or 1869, yet his true birth year was 1862. He was living at 35 St Michael’s Road Bradford, and his employment was correctly recorded as dyer.

His wife was Sarah Ann Smith, aged 21, a silk gasser living at 48 Crown Street Bradford, ostensibly daughter of George Smith, a retired joiner. A silk gasser exposed the thread to a hot gas flame to remove fuzz and excess lint.

By this point Arthur had a fifteen-year criminal record, so Sarah Ann must have been very much in love with him, or else she had a very limited choice of partner. She does not seem to have been pregnant at the time of marriage.

Indeed it is not straightforward to trace her history before she arrived in Arthur’s life. She might well be the same Sarah Ann Smith, born around 1872, who was in 1881 a boarder at the Fitzwilliam Street Ragged School in Huddersfield.

The School’s purpose was:

‘To reclaim the neglected and destitute children of Huddersfield by affording them the benefit of a Christian education and by training them in habits of industry so as to enable them to earn an honest livelihood and fit them for the duties of life.’

By 1891, she may be the same Sarah Ann Smith who was boarding with David and Effie Garrick at Mold Green, a Huddersfield suburb.

There is no sign on either of these census entries of her alleged father, George Smith. But perhaps he had been unable to care for her, possibly following the death or departure of her mother. He is not shown as deceased on the marriage record, though he is described as a ‘joiner (retired)’.

I have been unable to track him down.

Arthur must have made a determined effort to go straight for a while, but it could not last. The 1901 Census found him back in gaol, in the district prison at Wortley, near Leeds.

Meanwhile wife Sarah Ann is shown as still married, but working as a live-in housekeeper for one Jonathan Richard Haley, a 29 year-old woolcomber at 3 Mulgrave Court, Bradford. There were two children, both said to be Haley’s.

The 1911 Census recorded Sarah Anne, now aged 38, boarding with Joseph Dodgson a 59 year-old miner and his wife, Emma. Sarah Anne again has two children with her.

Strikingly, Sarah Anne claimed to be single by this point, which would suggest she had gained a divorce. For, if Herbert was dead, she would be listed as widowed. But I can find no record of such a divorce and I believe Herbert was already dead.

During his time out of gaol, Herbert managed to father at least two sons, though there is some doubt over the parentage of other children born to Sarah Anne:

- John William Dracup has two baptism records, the first dating from 4 August 1897, the second saying he was born on 18 June 1898 and baptised on 18 January 1899. In the first case, the family is living at 73 Longland Street; in the second, at 5 Bank Street. Herbert was given as the father, even though the 1901 Census says Haley was. John William was living with his mother in 1911 and was already employed as a worsted spinner.

- Arthur Dracup, born on 12 November 1898 and baptised on 18 January 1899, alongside John William. The service took place at Bankfoot St Matthew, between Little Horton and Odsal. Herbert was again given as the father. Arthur seems to have died in infancy, during the second quarter of 1900.

- George Dracup, born early in 1901, three months ahead of the Census. His baptism record claims he was born on 27 November 1901, but this must be an error for 1900 (He was baptised as George, the son of Jonathan and Sarah Ann Haley of 3 Mulgrave Court. The official birth record named him ‘George Haley Dracup’. However, the 1901 Census called him ‘J H Dracup’. George died in 1907.

- Albert Edward Dracup, born in 1907. The official record of his birth confirmed this name, but his baptism, which took place in July 1907, was in the name Albert Edward Haley Dracup, the child of married couple Jonathan Haley Dracup and Sarah Anne Dracup! He must have been conceived while Arthur was in gaol. Albert Edward was living with his mother in 1911, alongside John William – her two surviving children.

I can find no evidence that Sarah Ann married Haley, so theirs must have been an illicit relationship rather than a bigamous one.

Haley himself already had a short criminal record, gaoled for a month in January 1893 for stealing two valves and sixteen feet of iron piping. Perhaps he encountered Arthur Herbert in gaol, meeting his wife on release.

Haley died in January 1910 at the tender age of 37. Sometime later, in February 1917, Sarah Anne remarried, uniting herself with a 45 year-old widower called Thomas Whiteley, employed as a furnace cleaner. By this time she was 42 and living at Rashcliffe, a Huddersfield suburb.

.

.

Arthur’s Later Criminal Career (1895-1909)

But let us wind back the clock to Arthur’s own marriage.

.

1899

He would have been released in April 1896 and, as we know, his wedding day was 3 August that year. Thereafter he seems to have gone straight for three, almost four, years.

On 18 January 1899 the Bradford Daily Telegraph reported that ‘Herbert Dracup, labourer of Wibsey’ was found guilty of failing to report himself while being under police supervision.

He was sentenced to two months’ imprisonment under the Prevention of Crimes Act but, following an appeal by his wife, was discharged.

‘The stipendiary said the Bench were now satisfied that the prisoner had been working, but reminded him that he must regularly report himself or he would get into serious difficulty. The prisoner promised to do so.’

This shows that Arthur was back in Bradford and had managed to secure gainful employment at last, perhaps pleading the needs of his wife and young family.

The simultaneous baptism records of John William (his second) and Arthur are coterminous with this incident and might have had something to do with his failure to report.

Both describe him as a ‘dyer’s labourer’ so he has come down in the world somewhat, given that he was a full-fledged dyer on John William’s first baptism record in 1897.

.

1900

Then on 7 June 1900, the same paper reported that ‘Herbert Dracup (35) labourer, lodging houses, was charged with stealing a piece of cloth, value £2 6s 8d, the property of Mr Jonas Wilkinson, 43, of Hall Ings.’

This confirms that Arthur is employed as a labourer rather than a dyer, and is living in a succession of lodging houses rather than in a single rented property. As a former criminal, or simply for want of rent, the family must have been moved on more than once. It must have been a grinding, hand-to-mouth existence.

The family has one young child, a second infant having just died, and Sarah Anne was also now pregnant with her third child.

The Leeds Times also carried the story, though mistakenly called the defendant ‘Robert Dracup’ and the owner ‘James Robinson’.

In fact Jonas Wilkinson was in partnership with Joseph Whaley, though the company was called Jonas Wilkinson and Co. and had its warehouse at 43 Hall Ings.

The incident occurred on the night of 30 May. Arthur went to the warehouse and, describing himself as an employee of the Midland Railway Company, asked if there were any goods to be transported. Astonishingly, his ruse was successful.

He duly took a piece of cloth, 42 yards in length, signed the consignment book and left the premises. He subsequently cut it into different lengths and took the pieces to various pawnbrokers. He was committed for trial at the next Quarter Sessions.

On 29 June, the papers reported that he had been sentenced to 12 months’ imprisonment with hard labour. The Metropolitan Police Register of Habitual Criminals confirms that he returned to prison in Leeds.

His physical condition had deteriorated: he had scars on his left cheek and left side of his nose, as well as on the left side of his chest. He had also lost all but four of his upper teeth.

As noted above, he was still incarcerated by the time of the 1901 Census, but was released shortly afterwards, being discharged once more on 16 May. His wife and children were meanwhile living with Haley.

It seems that Sarah Ann had finally lost patience with him. Perhaps she had once believed she could reform him. Without a wife to keep him out of trouble, Arthur’s days of freedom were strictly numbered.

.

1901

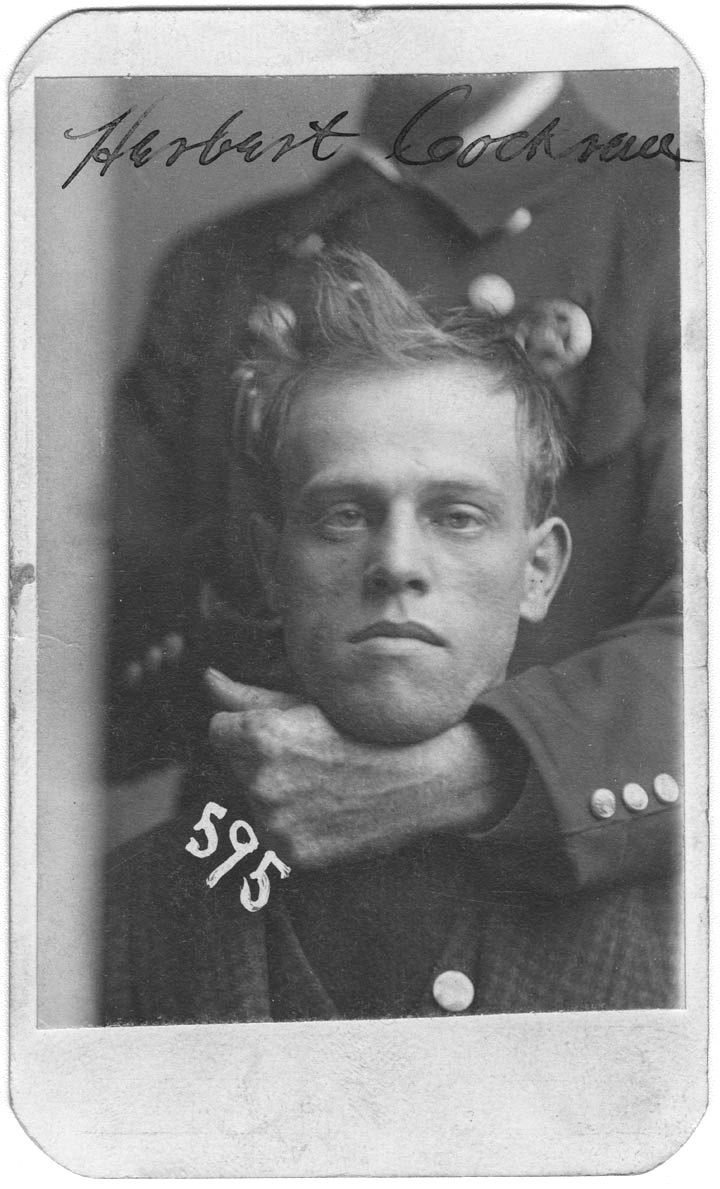

Just a few months later he was charged with stealing a watch, chain, jacket, vest and two shirts, valued at £3 10s and belonging to Dan Rowland, a miner, at Royd Cottages, Cawthorne on 3 August 1901.

According to one newspaper report, Arthur’s brother lodged with Rowland and he had gone to visit him. He was permitted to stay overnight but, when the others went to work in the morning, he stole Rowland’s property.

But another tells a slightly different story: the man lodging with Rowland was Edwin Ernest Brear, Arthur’s half-brother. Arthur met him at Cawthorne Basin on 2 August and, because he had nowhere to go that night, he arranged for him to stay ‘at Rowland’s premises, but not in the house’.

In the morning though, he let him into the house and left him there while he and Rowland went to work. Once Arthur had left the articles were missed and it was discovered he had pledged them at two Huddersfield pawn brokers for a total of 11 shillings giving the name ‘John Smith’.

He was arrested in Bradford on 16 August and tried on 14 October at Barnsley before Sir Thomas Brooke. He pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 15 months with hard labour at Wakefield Prison.

The record shows Arthur was now employed as a cook. He was discharged on 7 November 1902.

Coincidentally, Edwin Brear served time himself in 1913, convicted of three counts of attempted incest with his daughter Mabel, then aged 15.

.

.

1904

On 24 June 1904, the Bradford Daily Telegraph reported that Arthur had pleaded guilty to stealing a suit of clothes and a pair of boots valued at £2, the property of one Fred Hudson, on 2 May.

He was once more described as a dyer. Given his nine previous convictions, he was sentenced to a second helping of five years’ penal servitude. The judge described him as ‘a hopeless character’. He was sent to Dartmoor.

Dartmoor prison was originally built to house Napoleonic POWs, but was reopened as a civilian prison in 1851. It has Grade 2 listed status. When Pentonville Prison closed in 1885, Dartmoor was used for the probationary stage of male convicts’ incarceration.

Here is an extract from ‘Five Years’ Penal Servitude’ by One Who Has Endured It (1878) which describes the author’s arrival at Dartmoor.

.

.

.

This is the author’s description of a Dartmoor cell:

.

.

Arthur transferred to Wakefield on 20 August 1907 after three years in Dartmoor and then, on 11 April 1908, released on license to Shipley, care of Bradford Aid, for the remaining year and 73 days of his sentence, that license to expire on 23 June 1909.

His record refers to his occupation as dyer once again and carries the abbreviation DPAS – Discharged Prisoners Aid Society.

By 1872 there were 34 such societies across Britain. The Bradford Discharged Prisoner Aid Society was formed in 1883 under the Presidency of the mayor of Bradford and had its office at 41 Horton Lane.

From 1877 societies could apply to become certified and, in consequence, receive up to £2 per prisoner they assisted. They were responsible for providing ex-jailbirds with food, clothing, accommodation and work.

At this point we lose sight of Arthur.

.

.

Why was Arthur an Unashamed Recidivist?

Arthur spent half of his adult life in gaol, two slugs of it in convict prisons undertaking spells of penal servitude:

1881: one month

1882: one week

1882: two months

1883: three months

1884: nine months

1886: one year

1888: eight months

1890: five years (serving four)

1895: six months

1900: 12 months

1901: 15 months

1904: five years (serving four)

On each of his two convict sentences, he would have spent the first nine months in solitary confinement in his cell. Even exercise would normally be undertaken alone and the only occasion for meeting fellow convicts would during the weekly chapel service.

Subsequently he would work during the day, spending the rest of the time in his cell or in a dormitory, and could associate with fellow prisoners.

On completion of his sentence he was released on licence. This was usually for a quarter of the sentence remaining once the solitary element had been completed.

The local prisons, where Arthur was for the remainder of his prison time, followed a variety of different regimes, most often the ‘silent system’ were prisoners could associate during their work but were not permitted to talk, and the ‘separate system’ involving solitary confinement and masks to prevent communication during exercise and chapel. Sentences were typically a maximum of two years.

‘Five Years’ Penal Servitude’ provides an interesting perspective on Arthur’s recidivism.

.

.

It is easy to imagine that Arthur’s cards were marked as soon as he sought fresh employment, even if his reputation hadn’t already preceded him. His alternatives were few, more often than not to return to prison or go into the workhouse. There is no evidence that Arthur ever chose the workhouse.

Bradford Workhouse was built on Little Horton Lane. It initially prioritised the able-bodied, but soon switched its attention to the aged and infirm. A porter directed new inmates to the receiving wards or the vagrants’ ward where they were stripped and clothed in a workhouse uniform.

Workhouse guardians typically preferred to employ a strong master who would rule with a rod of iron, so maintaining order and control, but several Bradford incumbents were unsuccessful, a few condemned for drunkenness, incompetence or other shortcomings.

Because the able-bodied were deemed a lower priority they encountered poorer conditions and fewer ‘treats’. Although more open than a prison, pauperism was thought just a step away from criminality. By 1901 there were just 74 able-bodied paupers accommodated in the Bradford workhouse.

Vagrants were lowest in the pecking order. They would not receive supper if they arrived after 20:00 and the following morning might be allocated thankless work tasks such as stone-breaking. Vagrants continually rebelled, often seeking to escape the workhouse rather than undertaking such work.

The stigma attached to able-bodied pauperism may have made the criminal life more attractive to Arthur and his ilk.

.

.

Arthur the Dyer

The dying industry had developed rapidly in the mid-19th Century.

In the 1840s, dyers relied almost exclusively on natural dyes – such as madder root, cochineal, the indigo and woad plants – and a few chemical dyes. Whereas, by the time Arthur became a dyer, synthetic dyes were increasingly common.

Some sense of the recipes involved can be gained from A Complete Treatise on the Art of Dying Cotton and Wool (Ulrich 1863).

.

.

The Bradford and District Amalgamated Society of Dyers, Crabbers, Singers and Finishers was founded in 1878, though an Amalgamated Society of Dyers had already attempted a strike in 1874, when about 1,200 men downed tools at Horton Dyeworks and at Oates, Inghams and Sons Dyeworks (though those at Bowling Dyeworks remained at work).

Local newspaper reports estimate there were at this time between 2,000 and 3,000 dyers in Bradford, most of them earning between 14 and 24 shillings a week. The lower paid were earning similar wages to unskilled labourers.

There were only 77 members by the end of the 1870s. But in 1880 there was another dyer’s strike in Bradford, calling for a reduction in working hours to 54 hours a week, with wages unchanged.

On 20 February, some 2,000 dyers employed by Pottersgill, stormed the works of Oats, Ingham and Sons in an effort to persuade them to come out in sympathy. The police were called out to defend Inghams.

Some dyers returned to work but a hard core were resolute. An arbitrator was called in who eventually recommended that the dyers’ case should be accepted. This success enabled the Society to recruit rapidly, reaching 700 members in 1884 and over 1,800 by 1891.

From 1891 to 1892 it led another strike of 6 months’ duration at Manningham Mills which was unsuccessful but which led almost all local dyers to join. In 1892 it was renamed the Amalgamated Society of Dyers and, from the turn of the century, it began recruiting nationally, numbers reaching 4,000 by 1894.

Although Arthur may well have been blacklisted by local employers for at least some of his dyeing career, it is nevertheless interesting to match the calendar of his criminal acts against the timetable of industrial unrest, when poverty might have been expected to have been more widespread.

One imagines that most of Arthur’s contemporaries saw him as a feckless and irresponsible criminal but, with the benefit of hindsight, it is much easier to empathise with him as the victim of a punitive system.

Once he had taken his first wrong turning, it must have been almost impossible for him to recover. Had he read ‘Five Years’ Penal Servitude’, he might have arrived at perhaps the only way out.

At the end of the book, the author writes:

.

.

One wishes that Arthur could have contemplated either temporary or permanent emigration abroad. He wouldn’t have been the first serial offender to cast off his criminal record that way. There would have been a certain irony in accepting ‘voluntary transportation’ of this nature, but it was an escape of sorts.

But although the end of his story is unknown, it is unlikely to have been a happy ending. Though we do not know Arthur’s date of death, he is almost certain to have fizzled out of existence some time before 1911. Did he successfully evade the workhouse during those final months of sickness and penury?

He was certainly deceased by the time his son John William married in 1917.

His widow, Sarah Ann Smith, went on to marry a third time – to Alfred Fenwick, a widowed worsted twister, in January 1940. She died in Huddersfield in January 1951.

.

TD

October 2019

amended

October 2023

.