This Dracup family history post, the 29th in the series, surveys three generations of Dracups.

It deals with the lives and experiences of George Dracup (1824-1896) and his wife Jane, nee Bullock (1824-1886), their siblings, children and grandchildren.

This will be the first of two linked posts.

In this part, I look first at George and Jane’s generation. Then I review the lives of the four of their children who chose to stay in Bradford, as well as the lives of their children, those of George and Jane’s grandchildren who were resident in England.

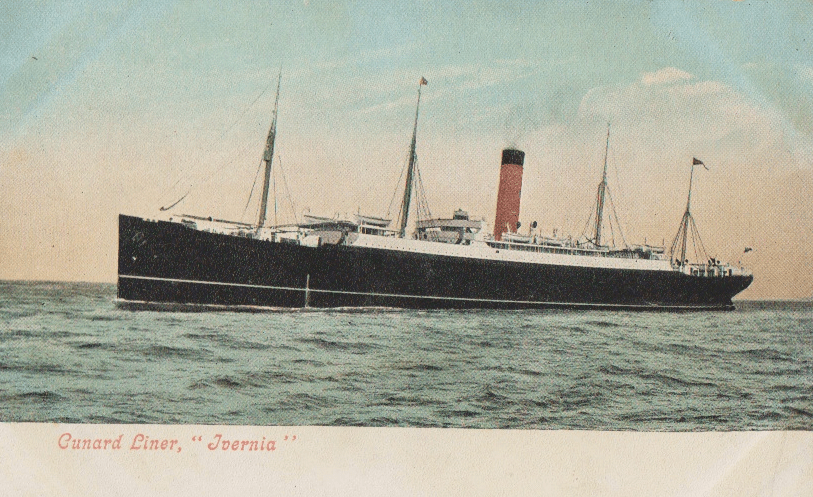

The second part will deal with the lives of four more of George and Jane’s children who emigrated to the United States, as well as their American grandchildren.

I intend to conclude with a comparison of these two parallel communities, separated by the Atlantic Ocean.

I am particularly interested in comparative living standards and quality of life.

To what extent did that depend on their country of residence, or on what we can infer of their characters? Were those who emigrated typically the bravest and best, who deservedly earned good fortune? Or did good fortune depend much more upon luck and fate?

George and Jane were relatively unusual because they left Bradford shortly after their marriage, raising a young family in Continental Europe before returning home to England in the 1860s.

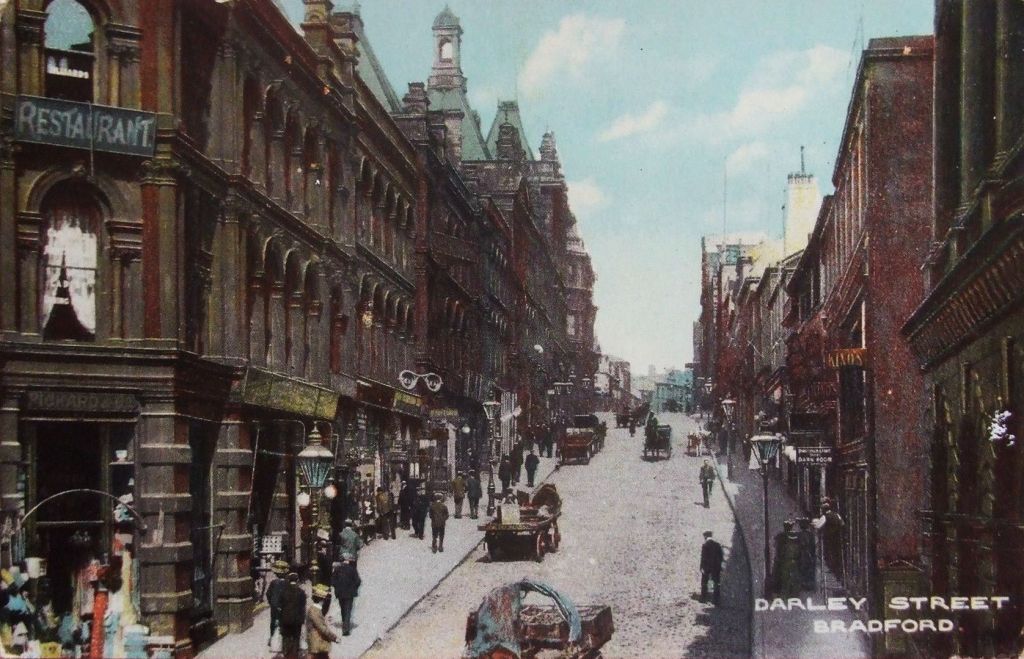

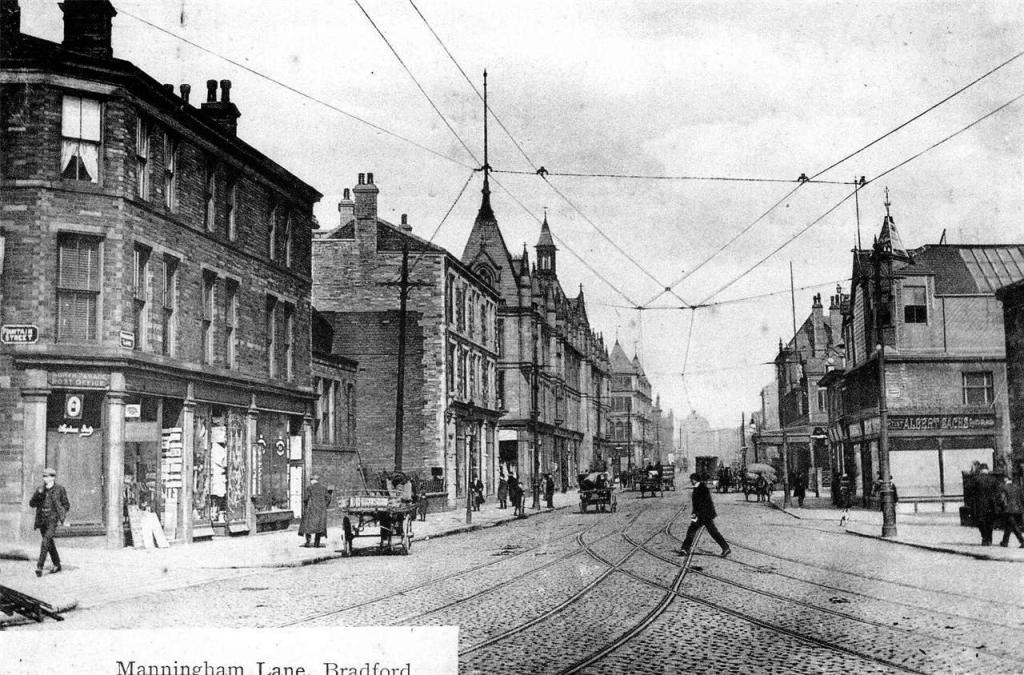

But most of the other principal characters in this post lived almost exclusively in Bradford, West Yorkshire, usually within a small area immediately to the south of the Town Centre, bifurcated by the Manchester Road and Little Horton Lane.

I have mapped out their residences for your convenience.

They were typically alive between the mid-Nineteenth and mid-Twentieth Centuries. For at least part of their working lives, many made a living from the sale of fruit and vegetables.

Not such riveting stuff, you may think, but you would be quite mistaken.

Aside from the Belgian episode, this post features a terpsichorean interlude, several bankruptcies, much low-level criminality, a smattering of adultery and illegitimacy, a false marriage and a false identity.

I believe I have also made some progress in resolving a few knotty problems in this section of the Dracup family tree.

George and Jane had up to twelve children all told.

But two sons definitely died before reaching adulthood; and two potential daughters mysteriously appeared in a single census apiece.

Of the eight remaining, four sons: William (1851-1923), Samuel (1856-1921), George (1860-1926) and Benjamin (1862-1928) all chose to remain in England. All of them married and all except William had children.

Another four children, two sons and two daughters, migrated to the United States: Albert Bullock (1845-1913), Henry (1853-1940), Mary (1857-1916) and Martha Jane (1859-1937). All of them married and had children.

This PDF chart shows the relationship between the individuals who feature in the first part of this post. (Warning – this is not a complete family tree.)

The sections below deal first with George’s and Jane’s parents and George’s siblings, then with each of the four sons who lived in England, their partners and children. It starts with the eldest son, William, and concludes with the youngest, Benjamin.

I have drawn on all the genealogical records I can find, as well as material in contemporary newspapers. I have laid out the facts that are in the public domain, making an occasional inference, based on probabilities, where I believe it justified.

I have tried not to be too judgmental.

Wherever possible, I have also tried to set these lives within their historical, social and economic context.

I’m happy to discuss anything you read here. If you have any further information or illustration that you are willing to share – and to have me share – please don’t hesitate to leave a comment or use the contact form provided.

George’s parents and siblings

George was born in 1824, the eldest son of Henry Dracup (1803-1862) and Mary, nee Haley (1803-1875).

When Henry married Mary, in St Peter’s Church, Bradford on 4 May 1823, he was described as a joiner.

George’s grandfather was his namesake, George Dracup (1775-1851), a shuttlemaker. He in turn was the youngest son of Nathaniel Dracup (1728-1798), George’s great-grandfather, a prominent Methodist preacher and the common ancestor of most living Dracups, if not all.

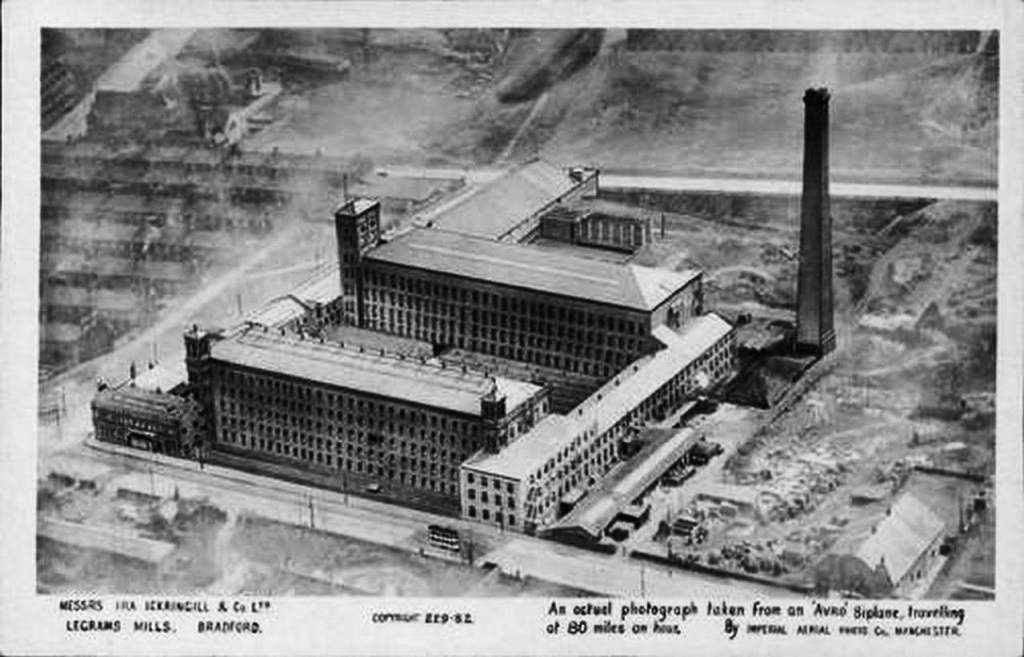

By the time of the 1851 Census, Henry’s job had become ‘mechanic’. He was most likely working with and for his brother Samuel Dracup (1793-1866), the Jacquard machine maker and the founder of Samuel Dracup and Sons.

George had three younger brothers – Luke, Lot and Adam – and three sisters who survived into adulthood – Mary, Ruth and Martha.

One, maybe two more Ruths died as babies, while two additional sons – William and Isaac – are mentioned in the 1841 Census, but I can find no further record of their existence.

George the youthful overlooker

The 1841 Census shows George already employed as an overlooker, at the tender age of 17.

Overlookers supervised the work undertaken by other employees, often spinners or weavers, but also those from other branches of the textile industry, such as combers and dyers.

They might be responsible for 30-50 workers or more, handling discipline, which might involve administering corporal punishment. They often recruited new staff, sacking those unable or unwilling to meet the standards they imposed.

They also undertook basic machine maintenance, calling in mechanics for more complex repairs.

Employers often expected their overlookers to be literate, as well as numerate, but this was far from universal.

Younger overlookers were cheaper to employ and likely more biddable.

As the textile industry expanded, looms became powered, and worsted replaced cotton, adult wages had generally fallen. By 1841, overlookers were typically earning some 24s to 30s a week. But average wages had recently fallen by up to 5s a week.

There were at this time 38 worsted mills in Bradford itself, plus another 28 in the wider borough, so 66 in all. That includes nine in Great Horton and 13 in Little Horton.

Roughly 10,400 people were employed, but only a minority was adult. And adult males numbered only some 460, many of them overlookers. Other contemporary sources suggest that some 200 overlookers were living in Bradford at this time.

This situation led to an exodus of adult males seeking gainful employment elsewhere, not least my own direct ancestors, one of them an overlooker, who left Bradford for the south of England around 1860.

Three brothers, two bankruptcies

Like George, his brother Luke (1829-1864) was an overlooker. He married Rhoda Dalby (1833-1868), and they had four children before both died young. Also like George, he didn’t trouble the newspapers.

But the other two brothers, Lot and Adam, neither of them overlookers, both feature by virtue of their bankruptcies.

During the early Victorian period, many bankrupts languished for years in debtors’ prisons, because it was widely expected that creditors should be paid in full before a bankrupt was released.

But under the provisions of the Debtors’ Act 1869, a bankrupt could avoid imprisonment provided that he disclosed to the appointed administrator all his property and assets, surrendering them when required, as well as making available all relevant documents and papers. He might still be imprisoned if he attempted to conceal significant property or debt.

All filings for bankruptcy were published in the London Gazette, and often carried in local newspapers too, so public humiliation was virtually guaranteed.

The appointed administrator would convene a first meeting, at which creditors could learn the state of the bankrupt’s affairs and question him under oath. This was followed by a public examination in court, after which all creditors were requested to submit evidence of their claims.

Once the bankrupt’s remaining estate had been sold, the administrator would calculate the amount available to repay creditors, typically expressed as the sum they would receive for every pound sterling owed to them. Sometimes there were two or more repayments of this kind before the bankrupt was released from his obligations.

Often, the meetings convened during this process would also be reported in the local press, as well as in the Gazette.

Lot Dracup (1831-1903) married Martha Airton (1832-1900) in 1852. They had six children, but their youngest daughter died in infancy shortly after Lot’s bankruptcy.

He was initially apprenticed to a blacksmith but, by 1856, had established himself as a bolt and screw maker working out of premises in Westholme Mill, on the Thornton Road. He and his family were resident at Back Lane, Little Horton.

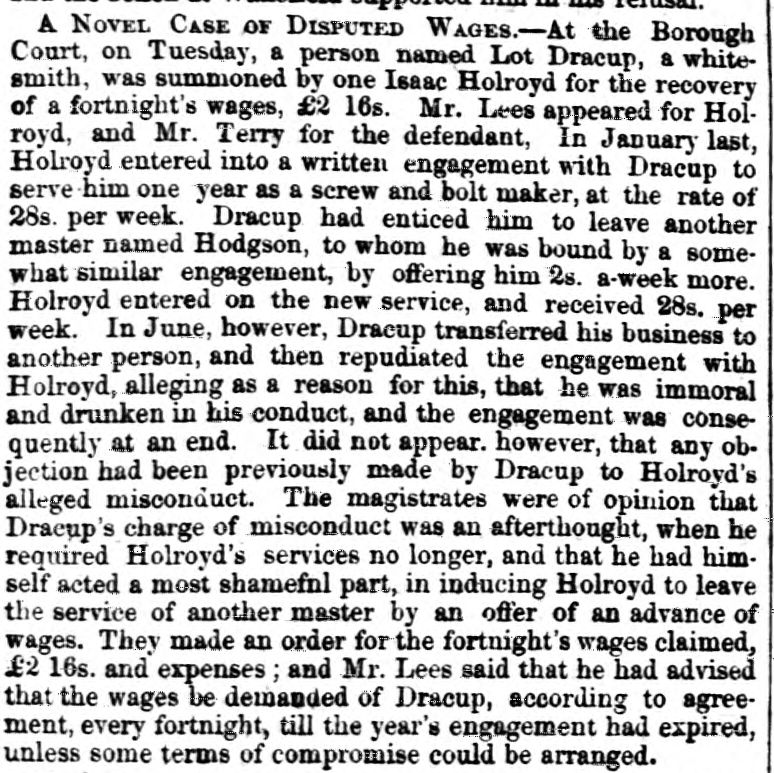

In July 1857 he was summoned to the Borough Court by his former employee, Isaac Holroyd, seeking recovery of a fortnight’s wages.

The Court heard that, in January 1857, Holroyd had entered into a contract with Lot to work for him as a screw and bolt maker for one year, at a rate of 28 shillings per week.

However, in June, Lot had transferred the work to a different employee, terminating his contract with Holroyd, alleging immorality and drunken conduct. He had not previously had cause to admonish Isaac for such conduct.

The magistrates ruled that the allegation was merely an excuse to terminate Holroyd’s employment, ordering Lot to pay the wages outstanding, and to continue paying them until the end of the year, or else reach a suitable compromise with Holroyd.

By the time of the 1861 Census, Lot was working as an ironmonger, having significantly expanded the range of products he manufactured. His work premises were now at 125 Chapel Lane, while the family lived at 13 Southfield Lane.

In January 1868 he was summoned for failing to obtain a dog license, paying a fine of £2 10s. But much worse was to come.

On 30 January 1869 he filed a petition for bankruptcy at the Leeds District Bankruptcy Court.

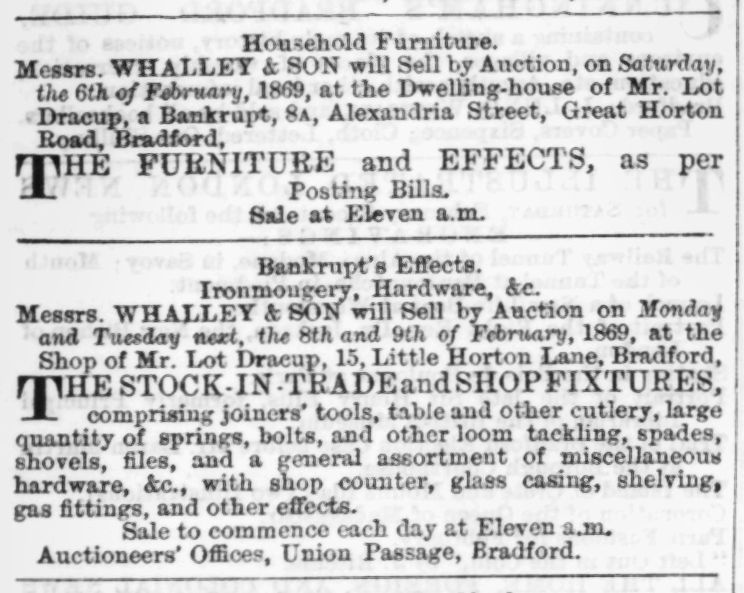

The Bradford Observer of 4 February 1869 carried twin advertisements: one announcing an auction of the furniture and effects from Lot’s family home, now 8A Alexandria Street, off the Great Horton Road, taking place on 6 February; and another announcing an auction of the stock and fixtures from his shop, now at 15 Little Horton Lane, scheduled for 8 and 9 February.

A notice subsequently appeared in the Leeds Mercury of 27 February, advertising his last examination and a hearing on Friday 10 March. At this, no opposition was offered and his bankruptcy was duly discharged. This was a much speedier resolution than was typically the case.

On Monday 2 August 1869, the Bradford Daily Telegraph carried a new advertisement declaring a marked change of career:

‘Lot Dracup, 3 Rand Street, Great Horton, Bradford, Auctioneer and Valuer, 20 years’ experience in Machinery. Goods sent for sale will receive his best care and attention.’

Lot was described as an auctioneer and valuer in both the 1871 and 1881 Censuses. By 1879, he had moved to 5 Greaves Street and by 1883, to 96 Ryan Street.

But, from 1887 he was no longer listed in the Bradford Directories and, in the 1891 Census, he was merely a ‘hardware salesman’, probably employed by someone else.

And, in 1901, now aged 67 and widowed, he had become a ‘general labourer’, residing on the infirm wards of the Bradford Union workhouse. He died just two years later.

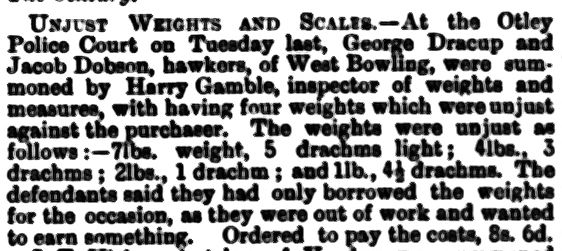

Adam (1833-1906) was in a rather different situation. We also know that he was a ‘lively’ young man.

His first appearance in the newspapers was a curious one, published in the Halifax Guardian of 12 June 1852.

At one o’clock one Sunday morning, a woman resident in Cropper Lane, Halifax, heard a young man crying out near her door that

‘he had been whalloped [sic] by a policeman’.

When another policeman approached, the woman

‘commenced a tirade of abuse’

later alleging that the policeman had struck her with his stick. The walloped young man – who turned out to be Adam – was called by the policeman as a witness to disprove her allegation.

In April 1856, the Leeds Mercury reported that Adam had been enlisted ‘by Serjeant Watson of the 16th Lancers at the rendezvous, the Beehive Inn, Westgate, Bradford’.

Having received his 3d enlistment money, he used it to buy gin, which he promptly drank, after which he refused to give his proper name and address. He was fined 10s, with 12s expenses, ‘or 14 days imprisonment with hard labour in Wakefield House of Correction.’

Then, in August 1859, he and another man, called Mark Schofield, were charged with a violent assault on Mr John Haley, woolstapler. The assault took place on a Wednesday night, near Summerseat Place, Horton Road, as Haley was on his way home from a concert in St George’s Hall.

Adam and Schofield reportedly attacked Haley’s companion, Zaccheus Wilkinson, innkeeper and, when Haley tried to intervene, set about him too. The pair were each fined 10s, with 18s costs, or 14 days’ imprisonment.

In August 1864, he was also charged along with two other men with stealing 4lb of mutton at Heaton, but all three were acquitted.

In 1868, he married Hannah Jackson (b.1832), a milliner, the daughter of Abraham Jackson, a farmer. At that time, he was employed as a mechanic.

I have already explored in a previous post, about Samuel Dracup and Sons, how Adam briefly set up as a Jacquard machine maker, presumably in direct competition with his late uncle’s Company.

At some point between 1871 and 1873, he formed a partnership with his brother-in-law, Abram Ambler (1844-1897), then a wool, cloth and waste dealer, who had married his sister Mary in 1868 (see below).

But they quickly ran into difficulties.

They initially sought tenders for the purchase of all or part of their business as a going concern. An advertisement says:

‘The premises have recently been fitted up with first-class plant and machinery, and the stock consists of about 300 new and secondhand jacquard engines, and a large assortment of valuable materials ready for use.’

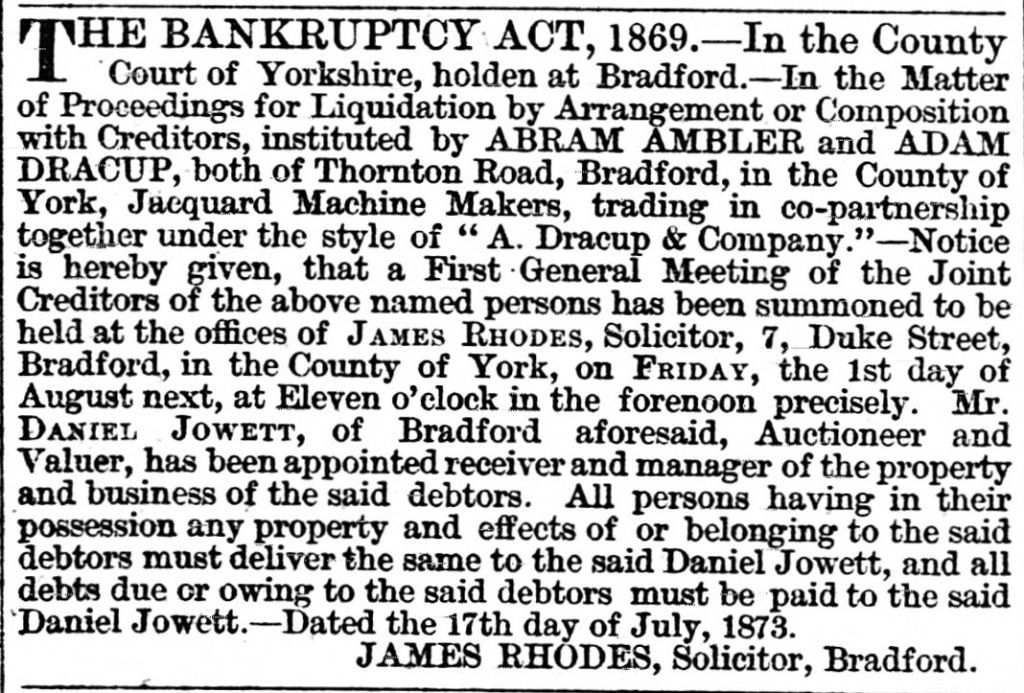

But there were seemingly no takers. In July 1873, the Bradford Observer carried a notice that the business – trading under the name ‘A. Dracup and Company’ – was entering liquidation by arrangement under the terms of the 1869 Bankruptcy Act.

A first general meeting of the creditors was to be held on 1 August. Daniel Jowett, auctioneer and valuer, had been appointed receiver. A slightly later notice announced that Mr Henry Ibbotson, public accountant, had been appointed ‘Trustee of the property of the Debtors’.

This meeting was reported in the Bradford Daily Telegraph of Monday 4 August. The pair:

‘stated that their suspension was owing entirely to the want of capital and the slackness of trade, and that if they could have carried on their business they were quite solvent.’

The liabilities were estimated at about £1,600, and the assets at £800. Two dividends were paid, one of 2s 6d in the pound from 15 January 1874 and one of just 5d in the pound from 10 June 1874.

Adam returned to his former employment as mechanic. After Hannah’s death in 1900, he married a woman more than 30 years his junior, fathering a daughter at the age of 70.

Three sisters and their husbands

As for George’s sisters:

- Mary (1836-1900) married the aforementioned Abram Ambler (1844-1897) in 1868. Previously a dyer, by 1871 he was a cloth dealer and wool and waste merchant, prior to his brief partnership with Adam. By 1881 he had returned to being a dyer’s foreman, but, by 1891, he was publican at the Adelphi Inn, 404 Leeds Road, Bradford. (The Adelphi seems to have been knocked down soon afterwards, as part of road improvements.) I think this is the same Abram, of no fixed abode, reported to have been discovered in a nearby greengrocer’s at 410 Leeds Road, helpless and of unsound mind, just before his death. According to a brief newspaper story, he was conveyed to the workhouse after being seen by a doctor. Although the probate record confirms that he died in the workhouse, it also gives him an address at ‘Akers Street, Leeds Road’. (I think this may be a misprint for ‘Acre Street’.) Abram left a little over £100. Mary went to live with her sister Ruth, dying at her address in 1900.

- Ruth (1845-1911) married Paul Woodhead (1835-1906), in June 1880. He was also a publican and a widower – his previous wife Sarah, nee Boothroyd, had died in January 1880. He managed several pubs in succession, including the Foresters’ Arms at Wibsey, the Brown Cow Inn at Cleckheaton and the Bottomleys Arms at Shelf. While at the latter pub, he was charged with being drunk at his own premises – and was fined £1 11s 6d. By 1898, he and Ruth were resident in Bradford, at 40 Watmough Street, he using the soubriquet ‘gentleman’. The 1901 Census described him as ‘living on own means’, now at 264 Great Horton High Street, where they lived with their only child, Arthur, a butcher. Paul left some £900 to his family; Ruth left over £300 at her death five years later.

- Martha Dracup (1846-1926) married Francis Holdsworth (1845-1917), an overlooker and later a mill manager. By 1911, he had retired and also referred to himself as a ‘gentleman’. They had six children, though only three sons and a daughter survived into adulthood. Martha and Francis afterwards lived with their (as yet) unmarried daughter at 780 Great Horton Road. Francis left some £1,200 to his family.

George marries and moves to Belgium

On 12 February 1850, now aged 26, George married Jane Bullock, also 26.

She was the daughter of Benjamin Bullock, a dyer, and his wife Jemima. She had been born in Barnoldswick, now part of Lancashire, but formerly within the West Riding. She was baptised ‘Jenny Bullock’.

Both husband and wife signed the record with a crude cross – their ‘mark’, so neither could write. There is every chance that they were unable to read either.

In 1841 Jane had been living with her family somewhere in the vicinity of Brick Lane, Manningham, employed as a worsted weaver. George had been living further to the south-east on Horton Road. It is quite likely that they both worked in the same mill and George might even have been Jane’s overlooker.

A first child, Albert, had been born five years before the marriage, on 18 April 1845, at Brick Lane, Manningham. The birth was recorded under the name ‘Albert Bullock’ (he later married under that name, but subsequently switched to Albert Dracup).

No father is named on the birth certificate. That might mean that George was the father, but was reluctant to lend his name to a child born out of wedlock, or it could be that another unidentified man was the father.

The family cannot be found in the 1851 Census, taken on Sunday 30 March, so the three of them – George, Jane and Albert – had most probably departed not long after the marriage. The birth of the next child definitely places them in Tournai, Belgium no later than August 1851.

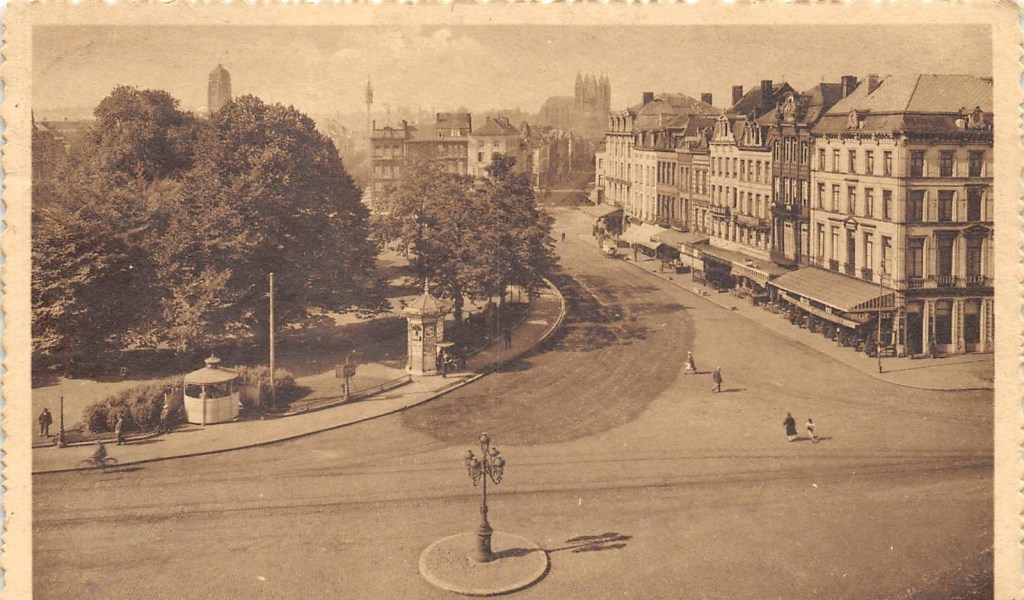

This contemporary map of Holland and Belgium shows the location of Tournai (within the province of Hainaut – no.18) and Liege (within the Province of Liege – no. 16) where the family moved after leaving Tournai.

Belgium was the first European country after the UK to experience an Industrial Revolution. Three sectors dominated: mining, metals and textiles. The first steam-powered mills were introduced in the 1820s and, by 1850, some 300 steam engines were employed within the textile industry.

It was not uncommon for British engineers and workers to migrate to other European countries at this time: thousands of British emigrants were employed in continental Europe, predominantly in the textile industries, machine making, railway construction and shipbuilding.

Sometimes they went because their employers were establishing businesses abroad, but many also went independently, responding to local skills shortages, or perhaps seeking improved pay and conditions. Belgium was a relatively popular destination because of its rapid industrialisation.

William Cockerill (1759-1832) had pioneered this relationship in the textile industry. Born in Haslingden, he was initially employed as a mechanic building machinery for spinning and weaving. He arrived in Belgium in 1799, via spells in Russia and Sweden.

From 1817 he began to establish a factory in Liege that specialised in steam-powered machinery. This proved highly successful, especially before the British lifted restrictions on the export of home-built machinery in 1843.

But it is important to underscore the comparative rarity of British workers in Belgium in the 1850s. Contemporary statistics, relating to 31 December 1856 and published by the Belgian Government in 1864, show that, while there were 43,000 foreigners living in the province of Hainaut, just 449 were from Great Britain.

The total population of the town of Tournai was more than 30,000, but only 31 of its residents were British. Fewer than 6,000 lived in the smaller town of Leuze, nearby, and just six of those were British. The comparable figure for the town of Liege – with almost 41,000 inhabitants – was 118 British inhabitants.

So this was a very brave step for a young man who couldn’t write (and probably couldn’t read) in his native language, let alone understand written or spoken French. He must have had to rely heavily on compatriots who had been in Belgium longer, for neither interpretation nor formal instruction would have been available to him.

Unless or until he learned some French, any form of integration with the local populace would have been problematic. He and Jane would have had recourse only to the small migrant community.

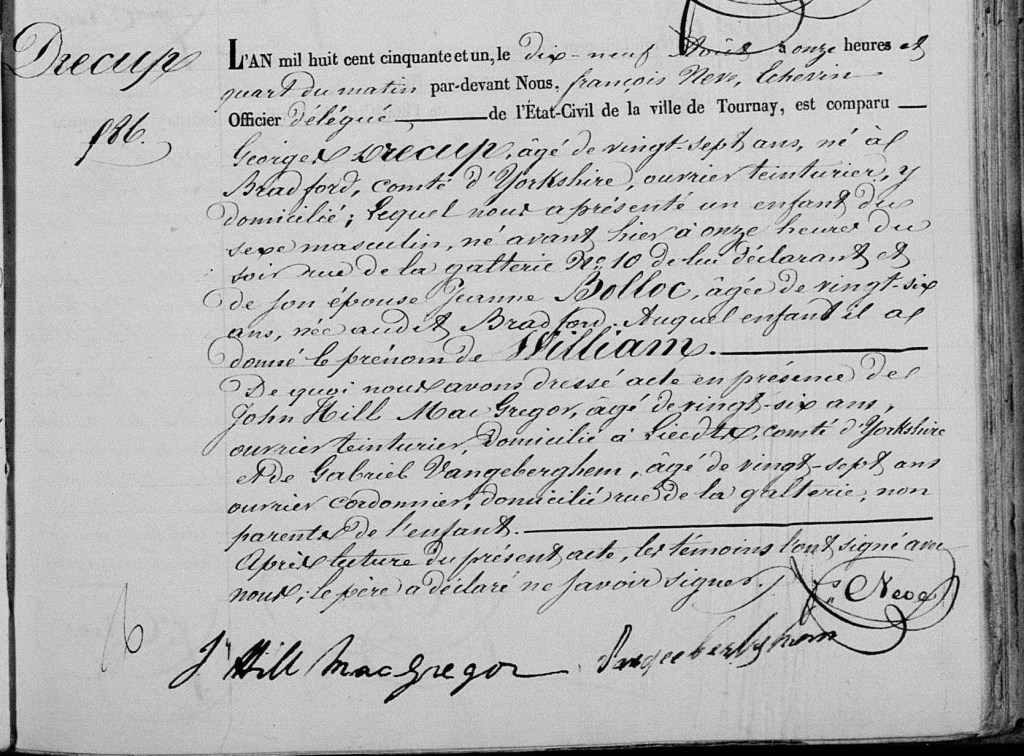

The French-language birth certificates for the two children born to George and Jane in Tournai tell us a little more about their lives.

Their first son born in wedlock, William Dracup, arrived at a quarter past eleven in the morning on 19 August 1851. He was born to ‘George Drecup’, 27 years of age from Bradford in Yorkshire, a dyer (‘teinturier’) and his wife ‘Jeanne Bolloc’ [sic], aged 26, also of Bradford.

Did the official spell these names as they were spoken to him, or had someone else written them out for George?

George was now working in a specialist area that must have been relatively new to him, and no longer had a supervisory role.

The family lived at an address that looks like ‘Number 10, Rue de la Galterie’. There is still a Rue de la Galterie some 20 kilometres east of Tournai, running between two villages, Chapelle-à-Gie and Chapelle-à-Wattines. The postal address was Leuze-en-Hainaut.

There were several mills located in Leuze. The present day Number 10 Rue de La Galterie is located near Chapelle-à-Gie. It looks relatively modern, but the cottage next door may have existed when George was here.

Two witnesses are named in the record. One was John Hill MacGregor, aged 26, from Leeds, another dyer; the other Gabriel Vangeberghem, aged 27, a shoemaker, also resident in the Rue de la Galterie. Both witnesses have signed the record.

John Hill MacGregor (1826-1897) and his wife Ellen, nee Appleyard, were definitely located in Tournai during this period, since several records exist relating to the birth of their own children. We also know that, by 1861, they had moved on to Wasquehal, between Lille and Roubaix in France. They did not return to England until some point between 1874 and 1881, reappearing in the 1881 Census.

Judging by his name, Gabriel Vangeberghem was a native Belgian, so probably a French speaker, and clearly George’s neighbour. He also appeared as a witness for two marriages and a death in Tournai between 1848 and 1852, but I can find nothing more about him.

The fact that George and Jane could ask him to be their witness might suggest that they were already able to communicate a little in French.

After William, the next five children – John, Henry, Samuel, Mary and Martha Jane were all born in Liege between 1852 and 1859, and, if there are records of their births, I can find no transcriptions.

There is relatively little about Liege in contemporary English newspapers, though it is occasionally described as ‘the Birmingham of Belgium’.

In June 1857, the Dundee Advertiser reported that a decision to cut the hair of some local convent school girls caught dancing on a Sunday led to riots, during which most of the convent windows in Belgium were smashed. This caused the King of Belgium to prorogue Parliament.

The Prince of Wales visited a cannon foundry at Liege in July 1857, on his way to Germany and there is much reference to arms manufacture in the Town.

In 1860, there was allegedly a shower of ants!

The population had recently climbed above 100.000, which suggests rapid expansion over the previous decade.

The important Liege-Guillemins railway station had opened in 1842, significantly improving transport links. The original wooden structure was replaced by an impressive stone building in 1863.

The final child to be born in Belgium was George, in January 1860, by which point the family had returned to Tournai. His birth record reveals that he was born at ten in the morning on 31 January, also to ‘George Drecup’, now aged 35, still working as a dyer, and ‘Jeanne Bolloc’, aged 34.

The fact that the two names are spelled identically on both records might indicate that George had asked someone to write them down for him, so that he could present them on occasions such as this. Or perhaps the official simply copied the previous record.

On this occasion their home address was given as Bradford, which may indicate that they had made a temporary stop at Tournai on their way home.

The witnesses this time were Francois Boutry, a weaver (‘tisserand’) aged 25, of Tournai and Justin (or possibly Gaston) Carbonelle, aged 30, also a weaver, of what could be Messy Ville or Merny Ville. Both are likely to have been French speakers.

I can find references to Boutry as a witness for other events in Tournai but, although the surname Carbonelle is popular, I can find no other reference in Belgian records to a Justin Carbonelle.

However, a man named Justin Carbonelle was born on 24 December 1836 in Paris, France, dying there on 25 December 1888. There are also many French candidates for the man named Francois Boutry.

George the Dyer

George was employed in Belgium – at least in Tournai – as a dyer, having previously been an overlooker in England. It is possible that he had spent some time as a dyers’ overlooker, or had been training himself in the skills required of a dyer, since he would otherwise have faced a very steep learning curve indeed.

If unable to read, as well as unable to write, he would have had to memorise the recipes for different dyes. Even if he could read, recipes written in French would have been difficult to decipher.

George is not the first dyer to feature here. Arthur Herbert Dracup, Career Criminal was also a dyer when not in prison, though he was working in the industry from about 1880 onwards, some thirty years after George.

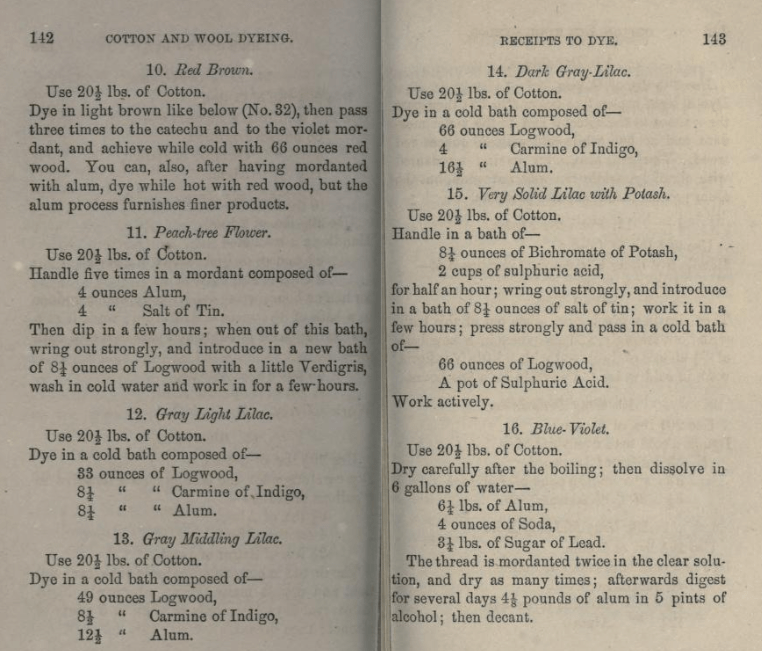

‘A Manual of the Art of Dyeing’ by James Napier (1853) is almost contemporaneous with George’s employment in France. It sets out in considerable detail the complex chemistry of dyeing.

The preface argues:

‘The trade is what is termed open, so that any man may enter it; and, in consequence, there are few instances where young men are taught the business systematically. A great many enter the trade who are grown up, – their chief ambition being to learn the mechanical operations of the dye-house, and when sufficient dexterity in these is attained, to secure the highest rate of wages. When this is accomplished, zeal for improvement in a great measure subsides. However, there are many who, not content with acquiring a knowledge of the mere mechanical routine, desire to look deeper into the principles of the art, and aim at higher honours than those of a mere labourer in it, but who believe that the means of success consist simply in long and steady service, and a good memory for the rules of manipulation. Both of these are valuable qualifications, but neither of them would be depreciated in the slightest degree by being conjoined with a more extended knowledge of the fundamental principles of the art than usually falls to the share of a practical dyer.’

Unless he was literate, George would have found these principles beyond him.

He may have been more attuned to a book I referenced in the post about Arthur Herbert: ‘A Complete Treatise on the Art of Dying Cotton and Wool’, translated from the French of M Louis Ulrich in 1863.

This was designed as a pocket manual for the workman or foreman, setting out the recipes for the mostly commonly used dyes.

At this period natural dyes were predominant, but synthetic dyes were just beginning to appear. Some of the first included: Mauveine in 1856, Magenta in 1858, Methylviolet in 1862 and Bismarck Brown in 1862.

George would have found himself at the heart of an industry that was developing rapidly.

But he left dyeing behind when he returned to England.

The family return to Bradford

The family – now comprising two parents and eight children – returned to Yorkshire at some point between 1 February 1860 and 7 April 1861, when the 1861 Census was taken.

They had been resident in Belgium for roughly 10 years, about eight of them spent in Liege.

The 1861 Census found them living in a newish house at 45 Ebor Street, just off Little Horton Lane. Ebor Street no longer exists, but was roughly where Bradford Ice Arena is today, just to the north of William Street.

It was apparently redeveloped in the early 1960s. The latest reference I can find to Ebor Street in a newspaper dates from 1956, while the ice rink was opened in January 1966.

It was located just to the south of Horton Lane Worsted Mill, the Church of St John the Evangelist lying in between. This had been constructed in the 1830s. It was later moved further down Little Horton Lane, but is now long since demolished.

George had returned to his former role, employed as a ‘weaving overlooker, stuffs’. He was now aged 37. Jane’s age was incorrectly given as 39.

Further children were born in the 1860s though there is some uncertainty about exactly how many.

- Benjamin was definitely born in Great Horton in the summer of 1862.

- Eliza, a daughter, born around 1865, makes a solitary appearance in the 1871 Census. (An Elizabeth Dracup was born in Dewsbury, Yorkshire in January 1865, but to William Dracup, a miner, and Martha, nee Law. I can find no other birth record under this name at this time.)

- A second Martha Jane, also apparently born in 1865, but in Great Horton, appears only in the 1881 Census. Was she perhaps the same person as Eliza? (A Martha Ellen Dracup was born in 1863, but belonged to a different family.)

- Fred was definitely born in the summer of 1867, in Bradford.

Within two years of returning to England, an older son, John, died, aged 12, on 10 June 1864.

According to the death certificate, an inquest was held at which the cause of death was determined as ‘injuries from the accidental falling of a hoist’. This was almost certainly an accident at work, quite possibly in the same mill that employed George.

I can find no reports about either the accident or the inquest in contemporary local newspapers.

By 1871, the family had divided into two households, as the three elder sons – Albert (26), William (20) and Henry (18) – found employment in Scotland. Albert was by this point married with a young child, while both William and Henry were bachelors.

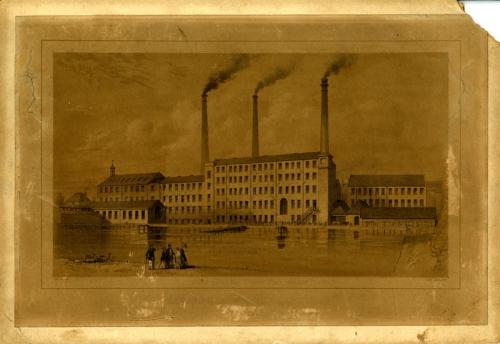

Their address was 79 College Street, in the Parish of Old Machar, Aberdeen, directly adjacent to the railway station. All three men were employed as worsted overseers, most probably at Broadford Works.

These originated in 1808 when Grey Mill opened. Under the ownership of John Maberly, an MP and businessman, and later his partner, John Baker Richards, the site expanded rapidly, becoming only the second linen weaving factory with power looms in Scotland. By the 1860s it employed some 2000 workers, the vast majority female.

Meanwhile, George and Jane had also moved a little further south-east, to 1, Newby Street in Bowling, just off Bowling Old Lane. This road also no longer exists, but, comparing new and contemporary maps, it seems to have followed what is now Stone Arches, running between Ripley Street and Bowling Old Lane, parallel with the Manchester Road.

George was still working as a worsted weaving overlooker, while Jane had returned to work as a worsted weaver. They had with them Samuel (15), working as a warp twister, the elder Martha Jane (13), George (11) and Benjamin (9), all worsted spinners. Fred (3) was still at school.

On 24 May 1880, Fred died from tuberculosis, following three days of convulsions, aged 13. The death was registered by Jane, who again left her mark, showing that she still had not learned to write.

The 1881 Census found George (now 58) and Jane (57) at 9 Mill Lane, in the parish of Eccleshill, a few miles to the north-east of Bradford. George was still an overlooker, Jane a weaver. Mill Lane is now called Victoria Road – it was renamed to celebrate Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee. The original house does not survive.

The other residents were their children, Benjamin, Samuel and the second Martha Jane. The original Martha Jane, newly married, was also registered as a visitor to the house.

It seems likely that George worked at Old Mill, Eccleshill, or possibly Tunwell Mills. Benjamin was now also employed as an overlooker and Samuel still worked as a twister, quite possibly at the same establishment.

Jane died on 4 February 1886, aged 62, of ‘acute bronchitis’. Her address was given as 51 Tichborne Road, the residence of her eldest son Albert Bullock and his family. The death was witnessed by Albert Bullock (using that surname), rather than her husband. She was buried in the Great Horton Wesleyan Chapel on 6 February.

By the time of the 1891 Census, widower George was living with his married daughter Martha Jane and son-in-law Thorburn Kennedy, at 14 Boynton Street in Bowling. No longer an overlooker, he was now working as a simple worsted stuff weaver.

When he died on 2 May 1896, aged 72, his address was given as 35 St Stephen’s Road, Bradford. His death was reported by Martha Jane Kennedy, living at the same address with her family.

George’s employment at the time of death was ‘wool comb minder’ and the cause of death was ‘chronic rheumatism; senile decay’. He was buried at Great Horton Wesleyan Chapel on 5 May.

Eight children definitely outlived George: William, Henry, Samuel, Mary, Martha Jane, George junior and Benjamin.

The remainder of this post deals with the lives of William, Samuel, George junior and Benjamin, the four sons who remained in England, and the lives of their spouses and children. I have introduced them in order of seniority.

William Dracup (1851-1923) and Mary, nee Collingwood

I cannot say definitively when William returned to Bradford from Scotland. His brother Henry married in Bradford in 1873, which might have been the signal for all three brothers to depart Aberdeen.

His own marriage took place in Bradford on 2 October 1877. By then 25, he married 20 year-old Mary Collingwood at the Parish Church (which was not made a cathedral until 1919).

The marriage record described him as an ‘overlooker of worsted spinners’ and, unlike his father, he was able to write his name. So could Mary, though no employment was recorded for her.

Her father was Joseph Collingwood, described here as a ‘beerseller and grocer’ and her address was ‘Gardener’s Arms, Horton’.

The Gardeners Arms was in Milton Street, a turning off the Listerhills Road, just after Preston Road. It was probably a two-room establishment, one serving as the grocery, the other as the beer room.

The 1830 Beer Act introduced the concept of a house licensed to sell beer, but not wine or spirits. Such licences were initially awarded automatically, subject to compliance with a few basic conditions and the payment of two guineas. But licences to sell wine and spirits alongside beer were much more strictly controlled, by local magistrates who had the power to revoke as well as award them.

By 1868 there were 400 beer houses in Bradford, but only 141 fully licensed premises. Then, in 1869, a law was passed which also brought beer house licences under the control of magistrates. In Bradford alone, 60 beer house licences were refused that year.

In July 1875, Collingwood applied for a license to sell intoxicating liquors and wine from his premises. He planned to give up the grocery side of his business. One report says he wanted to open an inn called the Melville Hotel.

He was apparently unsuccessful. His wife, Mary’s mother, died in 1879 and by 1881, he had retired, his census entry reading ‘formerly beerhouse keeper’.

By that point William and Mary were living at 109 Gaythorne Road. William continued as a worsted spinning overlooker while Mary had established herself as a corset and staymaker.

Corsets were typically made of cotton or wool. Whalebone was sewn in to provide flexible support, later replaced by steel. Corsets were typically strapless, often with front and rear fastenings, or else laced at the back. They were frequently colourful, often with a white lace trim.

They remained fashionable despite extensive discussion of their health risks. This is taken from the Bradford Telegraph of 27 March 1885:

‘Most women, from long custom of wearing the corsets, are really unaware how much they are hampered and restricted. A girl of 20 intended by nature to be one of her finest specimens gravely assures one that her corsets are not tight, being exactly the same size as those she was first put into, not perceiving her condemnation in the fact that she has since grown five inches in height and two in shoulder breadth. Her corsets are not too tight because the constant pressure has prevented the natural development of heart and lung space. The dainty waist of the poets is precisely that flexible slimness that is destroyed by corsets. The form resulting from them is not slim, but a piece of pipe, and quite as inflexible.’

By 1891, the couple had removed to 552 Manchester Road. William was now a ‘drawing overlooker’. Drawing is a process prior to spinning in which fibres are doubled, redoubled and compacted. Mary continued to develop her business. Two teenage nephews were living with them, both apprentices, and two lodgers besides.

We know they had only arrived here in 1890 because of this advert, which also suggests that Mary had been making corsets since well before her marriage.

The following year, some of her advertisements claimed her business had been established in 1868, when she would have been only eleven years old.

In 1901 they remained at the same address, both working from home. But while Mary was still making corsets, William had become a teacher of dancing.

William the dancing master

In February 1890 William had applied for a music and dancing license, for premises at 29 Addison Street.

However, the Chief Constable objected:

‘on the ground of there being a staircase, and the room being in an out-of-the-way place’.

The application was refused.

This makes more sense when one understands that the magistrates making such decisions were seized with a moral panic, fearing that dancing would encourage sexual expression, impropriety, or worse. They were determined to keep strict control over the number and quality of establishments operating in the Town.

This appeared in the ‘Daily Gossip’ section of The Bradford Daily Telegraph in October 1892:

‘The wave of morality sweeping over Bradford extends even to the harmless dancing room…The custodians of public morals appear to view the dancing hall with grave suspicion, and cold water was thrown on all applicants by the stern admonition of the magisterial spokesman. “We will never allow any Argyle Rooms to be set up in Bradford.” Possibly worse things than dancing rooms flourish in the Town!’

(The Argyle Rooms in London had acquired an unsavoury reputation as a place to meet prostitutes.)

By June 1891, however, advertisements had begun to appear for ‘Mr Dracup’s Dancing Class’, located at 46 Jacob Street, almost directly behind their home in Manchester Road.

Initially classes were offered on Monday, on Saturday and on Thursday evenings. Private lessons were also available. By the end of September the establishment was also open on Tuesdays. By November children’s classes were added.

It seems that, by providing tuition on the premises, William could avoid the need for a licence. The logical inference is that he became a dancing master primarily because he was initially unable to run a dance hall.

William was active as a dancing teacher during a seminal period in the development of modern English ballroom dancing. The waltz had been predominant for more than fifty years but, as the new Century began, a variation called the Boston was enthusiastically embraced, only for twin shock waves to displace it in the years leading up to the First World War.

Tango became a huge craze in Paris and soon crossed the Channel, while ragtime dances arrived on these shores alongside Irving Berlin’s ‘Alexander’s Ragtime Band’. Principal amongst these were the ‘animal dances’, namely the Bunny Hug, the Turkey Trot and the Grizzly Bear.

As dance schools proliferated, dance teachers began to organise themselves. The Imperial Society of Teachers of Dancing was formed in 1904; the National Association of Teachers of Dancing in 1907. The Dancing Times, first published 1894 and relaunched in 1910, enabled provincial teachers like William to keep in touch with all the latest developments.

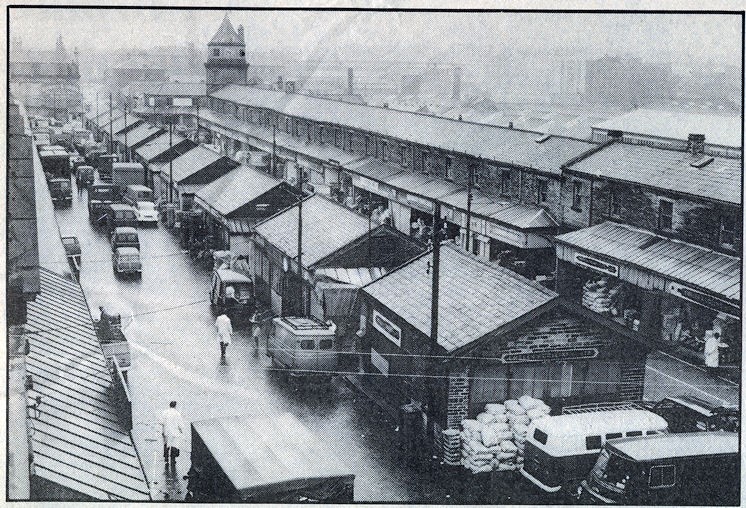

During this period, organised dancing for working class people was largely confined to public houses, municipal halls and small ‘assembly rooms’. Large public dance halls were rare, except in major seaside towns. Blackpool was most prominent amongst these, accommodating both the Tower and the Empress Ballrooms.

Unfortunately though, William’s second career was drawing to a close just as the public dance craze was really kicking off, immediately after the end of the First World War. As we shall see, William was already superannuated before the War started.

In January 1892 he applied for a music and dancing license for these new Jacob Street premises, but was again refused. Nevertheless, the dancing classes continued, William now claiming to teach the ‘Waltz and Schottische in four lessons’.

He also hosted private events.

In 1892 the West Bowling Primrose League had a tea and ball at Dracup’s Rooms, as did the weavers from Sugden and Briggs. In 1894 it was the turn of the Airedale Harriers and the All Saints’ Mission Cricket Club. In 1895, the Bradford Dolphin Swimming Club held a smoking concert.

In January 1896, the employees of Messrs B. and W. Brown held their annual social and dance in the Rooms, which ‘had been nicely decorated for the occasion by Mr Dracup’. Also that year, St Stephen’s Harriers held their annual ball there.

In December 1896 a newspaper advertisement referred to:

‘DRACUP’S CITY DANCING ROOMS, 369 MANCHESTER ROAD (next door to Manchester Road Station). Mr DRACUP will open the above LARGE BALL ROOM TONIGHT (TUESDAY) December 8. The best appointed Ball Room in Bradford.’

Next day, the Bradford Daily Telegraph carried a report:

‘OPENING OF A NEW BALL ROOM – Mr Dracup, the well-known dancing master, opened last night a new and well-appointed ball room at 369 Manchester Road. The rooms were crowded. The ball room itself is of an area of about 240 yards, fitted with a first class dancing floor, and tastefully decorated. There is also every other necessary accommodation in the shape of cloakroom, ladies’ and gentlemen’s dressing rooms, lavatories, etc. The rooms throughout are beautifully decorated and well-lighted, while the ventilation leaves nothing to be desired. Mr Dracup informs us that the rooms are engaged up to the end of March.’

In January 1897 his application for a music and dancing license for these premises was finally approved. The solicitor who made the application on his behalf said diplomatically that he ‘quite concurred with the remarks made by the Chairman about the late hours to which dancing was kept up’.

Prior to the Chairman’s remarks, the Chief Constable presented an annual report, stating that there were 284 places licensed for public music, dancing and entertainment in the Borough. These included 11 assembly rooms with music and dancing. There had been no convictions for impropriety. Places licensed for music and dancing had been visited frequently ‘and found to be carried on properly’.

The Chairman was a Mr W Oddy. These were his remarks:

‘…the bench did not think that the keeping open of these places (dancing halls) until two o’ clock in the morning was conducive to the morals or the health of those who attended them. A great many of these licensed music and dancing places were frequented by the working classes, and there were often cases where the fathers and mothers had to stop up to wait until after two o’clock in the morning before their children came home, and then they were knocked up again at five o’clock to go to work at six. If arrangements could be made for the places to be closed at say twelve o’clock, it would be much better. If it was necessary that they should have so many hours they might commence dancing earlier, say at half past seven or eight o’ clock, instead of nine or ten o’clock.’

This advertisement from December 1898 reveals that William had also developed a nice sideline in ballroom floor polish!

Dracup’s Assembly Rooms

William soon settled on the name ‘Dracup’s City Assembly Rooms’ (although ‘City’ was often dropped). In 1898, the West Bowling Cycling Club held their annual ball there, as did the Bradford Harriers. In 1900, it was the turn of E and F Troops of the Yorkshire Hussars. In 1904, the weavers of Isaac Sowden and Sons booked the venue.

Few adverts appeared between 1903 and 1909, if any. Perhaps they weren’t necessary.

In 1908 an article declared:

‘The twenty-first annual dancing season at Dracup’s City Assembly Rooms, Manchester Road, opened last evening and, judging by the events which have been already booked, the season promises to be a very busy one. There was a large attendance last evening and the rooms were beautifully decorated for the occasion. Many alterations for the comfort and convenience of the patrons have been made. A thorough system of ventilation has been installed, and plants, mirrors and statuary make the suite of rooms one of the most attractive in the city, and they may be used not only for dances, but all kinds of parties. The instrumentalists will in future be accommodated in an alcove, which has been constructed from the ball-room. In addition to the ladies’ and gentlemen’s retiring rooms, supper, smoke and card rooms are also provided. The ball-room floor is considered to be one of the finest in the country, being kept in beautiful condition by Dracup’s special preparation. It may be interesting to mention that attached to the rooms is a very nice bowling green, which should be an additional attraction during the summer season.’

When advertisements resumed in 1909, William was offering assemblies every evening except Friday, plus classes from three to five on Tuesday and Saturday afternoons.

In 1910:

‘The winter season was opened at Dracup’s Assembly Rooms on Tuesday night, and throughout the winter the spacious and well-appointed rooms in Manchester Road will be the resort of lovers of dancing on almost every evening…Judging by the attendance on Tuesday roller skating has not affected the popularity of the older winter diversion.’

The 1911 Census recorded William, now aged 55, and Mary, 52, still employed as ‘dancing master’ and ‘corset maker’ respectively, but their home address was now 389 Manchester Road.

It confirmed that there had been no children, alive or dead.

Subsequent advertisements reveal that, by November 1911, the Assembly Rooms had also moved down the street, next door to their home, at 387 Manchester Road. This must have been somewhere in the vicinity of the Station Hotel, but on the opposite side of the road, at the junction with Bowling Old Lane.

In 1913 the local paper mentioned that, for the 25th year in succession, Devine’s Band was supplying the music for Dracup’s Assembly Rooms. The leader of Devine’s was Frederick Parker Devine (1855-1931), a former worsted overlooker who had turned to music, as William had turned to dance.

On December 23 1913, an additional entry was published underneath the standard advertisement for the Assembly Rooms:

‘IMPORTANT NOTICE

Mr WM DRACUP (Dracup’s Assembly Rooms) wishes to inform the public that he neither Encourages nor teaches THE TANGO or any other Fancy Dances; and when he was MC at Blackpool Empress Ballroom he never allowed any fancy dancing.’

The Empress Ballroom was part of Blackpool’s Winter Gardens. Built in 1896, it was one of the largest in the world, boasting a floor area of 12,500 square feet. I have been unable to establish the veracity of William’s claim.

As for the tango, from as early as January 1911 newspapers began to report the latest dance craze sweeping through Paris. This is from the Liverpool Evening Express of January 11 1911:

‘The new dance which is holding Paris in thrall this season is the Argentine Tango, which hails from the great South American Republic. It was created in the popular halls, then refined and adopted by the upper classes, and recently imported by proud hidalgos into Parisian drawing rooms. It is a combination of the undulating body movements of the Spanish dances and the rhythmic arm movements of the American dances. The position is that of the Boston, and is retained throughout the dance. The cavalier never leaves his partner. The Tango is composed of numerous figures, the first being in walking step. The cavalier throws his body slightly backward, and his partner throws hers slightly forward. The second is a gliding step, the body being inclined first to the right and then to the left, the American arm movements marking the cadence. Another figure is something like the closing and opening of a fan. The Tango is danced to slow music.’

It took until 1913 for the tango to hit Bradford. In May that year, the Bradford Daily Telegraph referenced a letter published in The Times:

‘The modern additions to the ballroom programme have greatly exercised the minds of staid and old-fashioned folk. Some of these dances are now arraigned as partly immoral and wholly vulgar. What degree of turpitude attaches to the Turkey Trot, the Bunny Hug, the Argentine Tango is made pretty clear in the course of the discussion. One correspondent alleges that the Turkey Trot is “a dance of purely negro origin frankly symbolic of those primitive instincts of human nature which it is the aim of civilisation to suppress, or at least keep under control”. If this be true, we are afraid that many of the new dances outrage the Terpsichorean code which bars “every gesture that is offensive to modesty and corruptive to innocence.” Judged by this standard and recalling the origin and symbolism of some of the new dances we think they stand condemned. Why have they been allowed to creep into so many London ballrooms? To begin with, the dances are a kind of revolt against the stagnation that had come over English dancing. It was perhaps too stiff and formal. Now dancing has run to the other extreme and threatens to become vicious.’

Meanwhile, several of William’s competitors were freely advertising tango lessons. By refusing to embrace it and these other ‘fancy dances’, he was aligning himself with the values (and dances) of a previous generation, and probably signing the death warrant of his business.

Advertisements for Dracup’s Assembly Rooms continued to appear until February 1915, but then vanished. The last reference I can find in the local press is to an annual social and dance held by the coating menders of Briggs Pollitt and Co, held in February 1917.

By the time of the 1921 Census, William was 67 and Mary 60. They declared themselves still employed, as dancing master and corset maker respectively, still living at 389 Manchester Road.

Mary’s business was also becoming outmoded, for this was the swansong of the corset. Either side of the First World War, brassieres and girdles began to replace corsets and stays. But no doubt some elderly customers stuck to the old ways.

Sadly, Mary was already suffering from the vulval cancer that was to kill her on 11 August 1922, aged 65, her address given as 3 Newton Street, just off the Manchester Road.

William died shortly afterwards, on 20 May 1923, aged 72, also at 3, Newton Street. Cause of death was given as arteriosclerosis and a brain haemorrhage.

The same person witnessed both deaths, one Kezia Davis. Perhaps she was a servant in the house, or employed as a nurse. I have been unable to establish her identity.

Probate for William was awarded to his nephew Harry Dracup, a grocer (see below) and Charles Broadbent, a hairdresser. He left £347.

I have been unable to discover William’s relationship with Charles Broadbent. He was born in 1859 in Mytholmroyd and, by 1921, aged 69, lodged at an address on the Bolton Road. He had a hairdressing business located at 928 Leeds Road.

Samuel Dracup (1856-1921) and Jane, nee Hardwick

Samuel had not accompanied his brothers to Aberdeen, most likely because he was only 15 in 1871. He remained in the family home, in Newby Street and was employed as a warp twister.

A warp twister was responsible for operating the machine that wound and twisted threads, often into a cord, or else linked the end of one thread to the beginning of the next.

Samuel was still a twister in 1881 and was still living at home. But he married Jane Hardwick on 5 November that year. He was 22, she 21. He had moved from 9 Mill Lane but remained in Eccleshill, at 9 Holdsworth Square. Jane was also resident in Eccleshill, on Chapel Street.

The marriage record states that she was the daughter of Henry Hardwick, giving no occupation, but it seems more likely that she was born at Apperley Bridge, to Richard Hardwick (1824-1860) a waterman, and Hannah, nee Illingworth (1818-1891). Given the location, her father most probably worked the Leeds and Liverpool Canal, constructed between 1770 and 1816.

The birthplace of Samuel and Jane’s first three children was Idle, not far from Apperley Bridge, indicating that the family was resident there from 1882 to 1888.

But, by 1891, they had moved to 154 Spring Mill Street in Bowling. Samuel was a ‘silk warp twister’ and there were now four children.

They may not have remained too long at this house: it was shown as ‘to let’ in newspaper adverts from July 1891. There were two bedrooms and a side scullery and the rent was 4s 6d per month.

The birth of later children shows that they were subsequently resident in Liversedge, some miles to the south of Bradford, from at least 1892 to 1894.

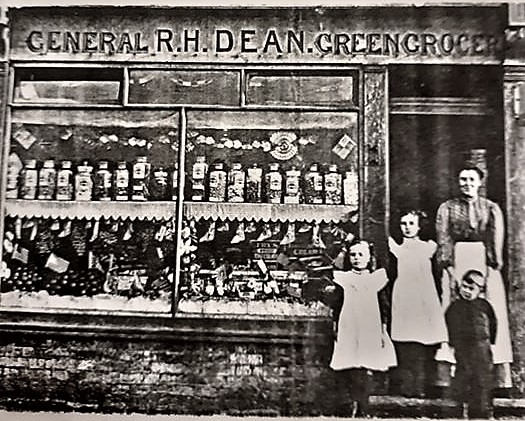

At some point between 1891 and 1901, Samuel also made a change of career. By the time of the 1901 Census, the family had moved to 228 St Stephen’s Road, a turning off the Manchester Road, not far from Ripley Street. Samuel had become a greengrocer and there were now seven children.

He was no doubt influenced by the career choice of many of his relatives (see below). But greengrocery was a temporary departure because, by 1911, he had returned to warp twisting. Their address was now 15A Bowling Old Lane, just round the corner from St Stephen’s road.

Samuel died on 14 March 1921, aged 65. Probate was awarded to his wife and he left £131. Their address at the time was 32 Jonas Gate, Bower Street, off the Manchester Road. This was close to Ebor Street and also no longer exists.

Jane and the remainder of her family were still residing at this address by the time of the 1921 Census. She described herself as a housekeeper and stated that she was married rather than widowed, even though Samuel had died three months earlier.

Jane died in April 1926, aged 65, her address remaining 32 Jonas Gate.

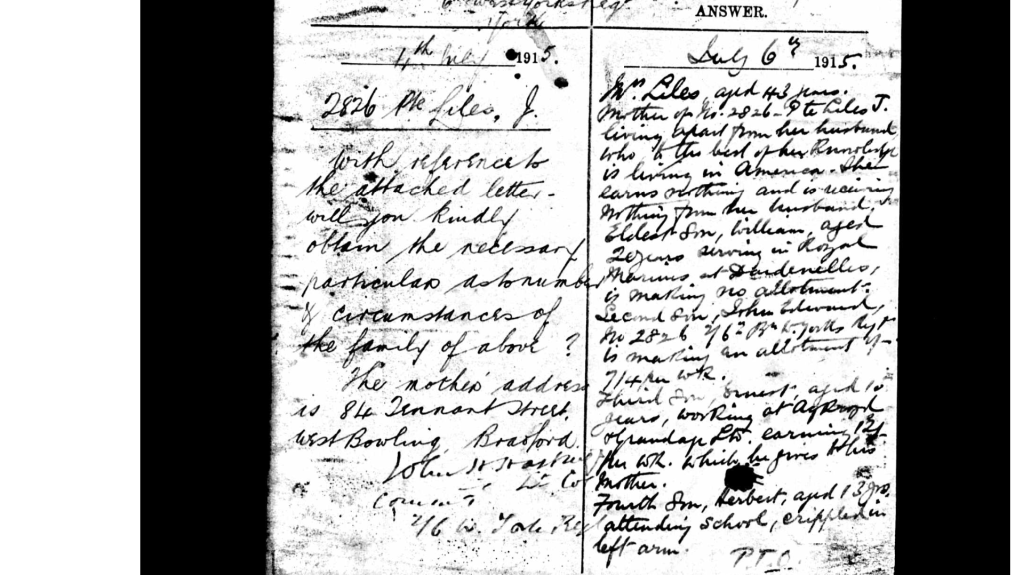

Altogether, Samuel and Jane had eight children, six girls and two boys.

Samuel’s and Jane’s daughters and their spouses

Like their parents, the daughters seem to have led fairly ordinary lives:

- Alice Maud (1882-1959) was born in Idle on 19 February 1882. At the time of the 1901 Census, she was a worsted spinner. By March 1910, when she married, she was a worsted twister, like her father. Her husband was Charles Elsworth (1884-1960), an ‘export maker up’ – essentially a packer – in a wool and worsted warehouse. In 1921 he was employed by James Edward Patefield, at 13 Union Street Bradford. (This was later the address of the British Cotton and Wool Dyers’ Association.) He was still employed in the same capacity in 1939. They had two children.

- Bertha (1884-1952) was born on 24 September 1884 in Idle. By 1911, she was also a worsted twister. In May 1913 she married James Chattaway (1882-1937), employed as a cycle/motorcycle packer and resident in Coventry. In 1921, he worked for the Triumph Company, Priory Street, Coventry. They lived in Coventry throughout James’s life, but Bertha returned to live in Spen Valley after WW2. She and James also had two children.

- Eva (1887-1889) died in infancy, aged two, on 21 September 1889, at 12 Spring Street, Idle, from a combination of measles, bronchitis and pulmonary oedema.

- Minnie (1888-1951) was born on 20 August 1888 in Idle. By 1911, she too was working as a worsted twister. In October of that year, she married Fred Fawcett aka Fred Fawcett Morley (1884-1944), then a self-employed hairdresser. They had one son. By 1921, they too were resident in Coventry, and Fred was employed as a painter by the Humber Car Company. However, by 1939, he had returned to hairdressing. After his death, according to the annotation on the 1939 Register, Minnie changed her name by deed poll to ‘Minnie Morley Fawcett’.

- Blanche Catherine (1892-1970) was born on 10 May 1892 in Liversedge. By 1911 she was employed as a burler and mender, working with ‘dress woollen goods’. (A burler removed imperfections in the cloth.) In October 1924 she married Herbert Wilfred Avison (1886-1952), a mechanic and engineer specialising in textile machinery. By 1921, he was self-employed, working out of Northgate, Cleckheaton. And, by 1939, with war approaching, he was working as an aircraft tool fitter. A child living with Blanche and Herbert at the time of the 1939 Register was actually their niece, Joyce, Gladys May’s daughter (see below). A reader who remembers Blanche recalls her mentioning that Harry Ramsden (1888-1963) of chip shop fame had courted her in her youth, but she had turned him down. This picture is taken from her niece Joyce’s wedding photograph, provided by the same reader. It was taken in 1942.

- Gladys May (1896-1973) was born on 19 September 1896, in Bradford. By 1911 she was a worsted spinner and, by 1921, also a burler and mender, but unemployed at the time of the Census. She gave birth to a daughter, Joyce, in June 1922 in Bradford. No father was named on the birth certificate. Then in April 1929 she married Herbert Risdon (1890-1962), a dyers’ labourer, following the death of his first wife, Maude Kathleen Shaw (1890-1927). Herbert had served in the Gordon Highlanders in the First World War. He was reported missing in May 1918, but by June was confirmed a prisoner of war. Gladys inherited four stepchildren, though one sadly died in the year of their marriage, and she had three more children with Herbert, all born in Bradford.

Samuel’s two sons were far more interesting subjects. Though both had relatively brief lives, those lives were packed with incident.

Edgar (1890-1930)

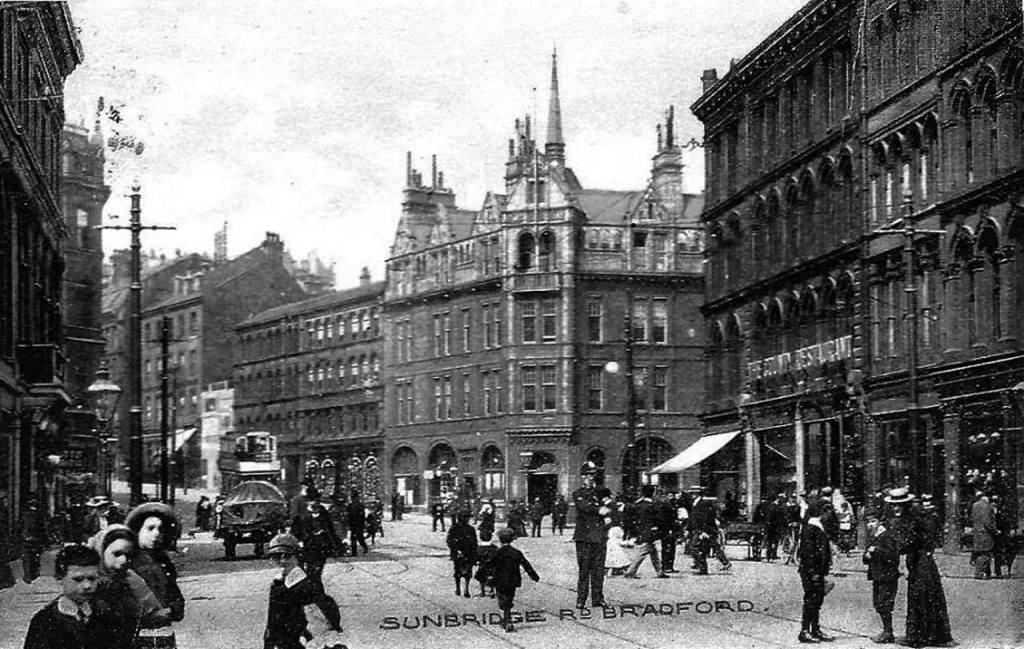

Edgar was born on 22 November 1890, at 154 Spring Mill Street Bradford, the address given by the family in the 1891 Census. Spring Mill Street runs south from the Manchester Road, crossing Ripley Street in the process.

During the 1911 Census he was one of 494 prisoners incarcerated in His Majesty’s Prison, Armley, Leeds. His age was recorded as 20, his employment ‘Iron Broker’, essentially a posh term for a scrap metal dealer.

The Bradford Daily Telegraph reveals that Edgar, now of 15 Bowling Old Lane, had been imprisoned for cruelty to a horse:

‘On March 2nd, the defendant and another man were in charge of an old bay pony and cart in Manchester Road. The defendant beat the horse continually for at least half a mile down the road until it fell exhausted in the road. The defendant was in a drunken condition.

Inspector Robinson of the RSPCA, who appeared to prosecute, said he examined the pony the day following, and found it to be in a very poor condition and very much worn out. It was totally unfit to work and had to be destroyed.

Defendant was sent to gaol for a month with hard labour.’

In January 1914 a gardener called Herbert Holt was imprisoned for ten months after stealing Edgar’s mare, valued at £12.

Edgar served in the Great War as a Private, initially with the Durham Light Infantry and then with the Labour Corps. I have not found his service record. His Medal Roll Index Card declares, in relation to his candidacy for a Victory Medal:

‘Service Not Approved. Medal forfeited.

Declared a deserter 15/12/18. Still in state of desertion 11/6/21.

Died 3-12-1930.’

On another record, it states that Edgar died ‘without making a confession of desertion.’

There is a Court Martial record dating from 28 August 1918, at Richmond. Edgar was sentenced to 42 days’ detention. It seems probable that, having served that sentence, he absconded a second time.

It is often thought that desertion was quietly forgotten about when the war ended, but that is not entirely true.

This Parliamentary Question was asked on 5 June 1924:

‘Mr. MACLEAN asked the Secretary of State for War whether any amnesty has been granted to those who deserted during the War; and, if not, whether it is his intention to offer an amnesty?

Mr. WALSH

The answer to the first part of the question is in the negative. As regards the latter part, I am not prepared to dispense altogether, by a general amnesty, with the right to try and punish men, in serious and special cases, for the grave military offence of desertion. The normal practice, however, has for long been to discharge the deserter without resorting to trial and without withdrawing him from his civil employment. I see no reason to vary this general policy, but I can undertake to consider sympathetically any particular case which does not appear to be covered by it.’

In October 1916 Edgar married Bridget Ann (Annie) Campbell (1893-1959), youngest daughter of a brickie’s labourer. Prior to her marriage she had been a worsted spinner.

By the time of the 1921 Census, Edgar was 30, still a self-employed metal broker working out of ‘no fixed place’. Annie was 29. One child, Eileen (1916-1918) had already died. Another, aged two, was still alive.

The family was living at 4, Crowther Court, Bradford, off the Manchester Road.

In January 1923, a report appeared in the Leeds Mercury of a court case in which Edgar was accused.

A metal dealer from Liversedge found him and two other men in his yard attempting to steal lead and copper cable he had stored there. The men ran away, but Edgar was apprehended and they found his horse and cart nearby. The report concludes:

‘It transpired there were twenty-eight previous convictions against the defendant, and he was fined 40s.’

In December 1923, he was fined 20s for ill-treating another horse:

‘It was stated that this was Dracup’s 26th appearance before the Court, and that he had been bound over for cruelty to a horse in 1909 and imprisoned for a month in 1911 on the same charge. There were several minor convictions for offences connected with horses.’

In April 1926, the Leeds Mercury reported:

‘When ordered to pay 4s costs at Bradford yesterday for allowing his horse to stray, Edgar Dracup of Broadbent Street Bradford, said the horse was an old circus horse which could jump the wall of the field, and which since the issue of the summons, had jumped the wall again and vanished.’

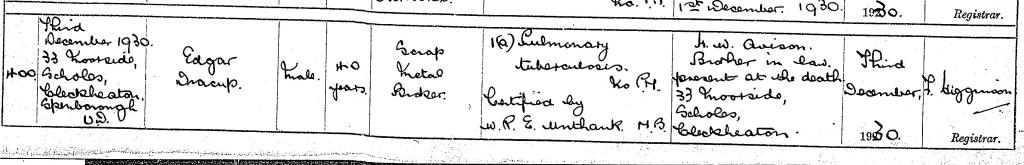

Edgar died on 3 December 1930, aged 40, of pulmonary tuberculosis. The record states that he was employed as a scrap metal broker and his address at the time of death was 33 Moorside, Scholes, Cleckheaton.

This was the address of his sister Blanche and brother-in-law Herbert Wilfrid Avison. Herbert was present at Edgar’s death.

Edgar and Annie had four daughters and one son, but only two daughters survived him, including their youngest child, born just before his death. Her birth was registered under two surnames: Dracup and Varley.

For Annie had remarried, in 1931, to William Varley (1886-1959) a widowed painter and decorator. There were several children from his former marriage, including a son aged five. Annie bore him three further children.

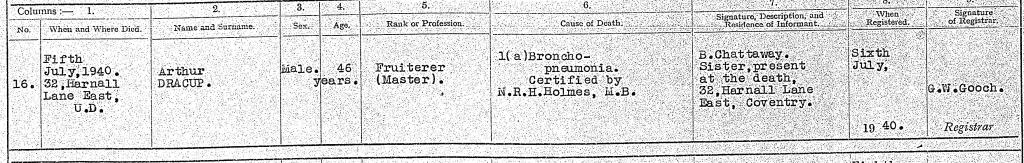

Arthur (1894-1940) and Mary Ellen, nee Wood

Samuel’s younger son, Arthur, was an equally colourful character.

He was born on 10 January 1894, in Hare Park Lane, Liversedge. In 1911, aged 17 and still living at home, he was employed as a ‘Dyehouse Boy’.

In 1914, now aged 20 and described as a ‘broker’ living at 15 Ripley Street, he was fined 5s with 5s costs for resisting a constable in the execution of his duty. The policeman was trying to arrest a hawker, called Albert Pickup for being drunk in charge of a pony and cart and animal cruelty. Pickup was fined 25 shillings and 10 shillings costs.

Four years earlier, Pickup had been admitted to hospital with ammonia poisoning. He had mistakenly swallowed some liquid ammonia thinking it was ‘ginger pop’!

In July 1916 Arthur was charged with obtaining by fraud a pair of boots worth £1 4s from a bootmaker called Edwin Lee, who had a shop at 484, Huddersfield Road, Wyke.

‘The prosecutor said the man came into get some boots, and displayed what he thought were a couple of half-sovereigns. Eventually, he bought the boots, giving the two coins referred to and two florins for them. Later the prosecutor found they were only tokens and not half sovereigns.’

He was sentenced to one month with hard labour.

By 1921, now aged 27, he was still living at home with his widowed mother and his sisters Blanche and Gladys. However, the census states that he was now married and employed as a hawker. His wife was not living at the same address.

Who had he married?

There were two marriages featuring an ‘Arthur Dracup’ in Bradford between 1911 and 1921. The earlier took place in the third quarter of 1913, involving a woman called ‘Kate Corley’. The later was in the second quarter of 1915, the woman named ‘Mary E Wood’.

I am finally clear that a different Arthur Dracup (1887-1975), a printer compositor, married Kate Corley on 19 July 1913. He had two children by a woman called Kathleen Florence, nee Corley, in 1923 and 1925 respectively.

I believe this is the woman, initially using the name ‘Kitty Corley’ and later ‘Kitty Dracup’, who enjoyed an extensive criminal career in the 1920s and 30s. She specialised in pickpocketing older males, usually working with a female accomplice.

At first I had assumed that Kitty Corley was the more likely match for this Arthur Dracup, but I was evidently mistaken! I shall have to postpone the fascinating tale of Kitty Corley until some other time.

That leaves Mary Ellen Wood, though she later went by ‘Mary Dracup’.

She had been born in April 1897 to Richard Wood (1872-1937), a wool comb minder, and Mary, nee Larvin (1877-1939).

Arthur and Mary Ellen married on 10 April 1915 at St Joseph’s Roman Catholic Church. He gave his address as 15 Ripley Street; she was living at 10 Jesse Street, off the Manchester Road. He gave his employment as ‘carter’, while she was a worsted spinner.

By the time of the 1921 Census Mary Dracup, aged 24 and married, an unemployed worsted spinner, was living with Charles Barker, a 44 year-old bag dealer, at 17 Salt Pie Street, Bradford. She was almost certainly Arthur’s wife, and probably already estranged from him.

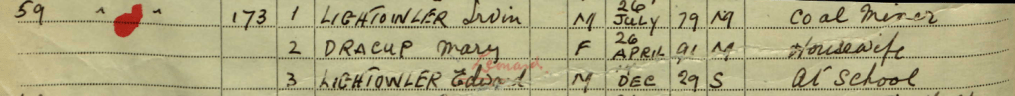

Other family trees link her to a spouse called Irvin Lightowler (born 1891), and a son, Leonard Lightowler (born 1929).

A boy called Leonard Lightowler was born to a mother with the maiden name Wood in Bradford, in the final quarter of 1929. There is also a parallel record for a Leonard Dracup, so the birth was registered under both surnames.

Moreover, the 1939 Register contained an entry for Irvin Lightowler, actually born on 26 July 1879, a married coal miner. Resident with him at 173 Crowther Street, Bradford were Mary Dracup, born 26 April 1891, a married housewife, as well as Leonard Lightowler, born 17 December 1929, now at school.

(There is also a second entry for Leonard Lightowler, born 14 December 1929, at Woodlands Convalescent home in Aireborough, Yorkshire. I assume both records refer to the same boy.)

Mary’s stated date of birth was some six years earlier than her correct birthday – 1891 rather than 1897. Perhaps she wanted to narrow the 18-year age gap between herself and Irvin Lightowler. Her death record says she was born about 1898.

Lightowler was still married to Clara, nee Ellis (1880-1962), that marriage dating from May 1902. They had four children. The family was still living together in 1921 but, by 1939, Clara was residing elsewhere in Bradford with one of their sons.

So it seems that Mary and Arthur were already living apart by 1921 and that, by 1929, at the latest, she was cohabiting with Irvin Lightowler. I can find no marriage record for Mary and Irvin. Nor can I find any record of children born to Arthur and Mary.

Until recently I had been unable to trace Arthur in the 1939 Register. But I have since discovered the reason: he had changed his identity.

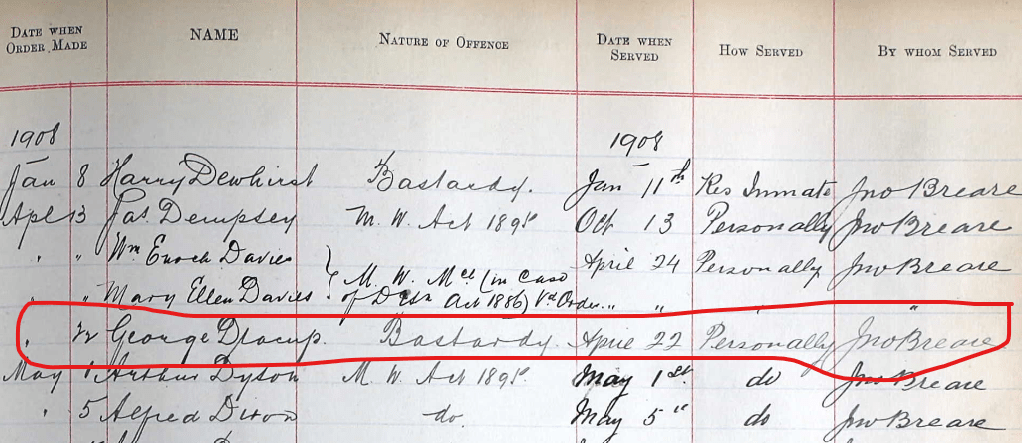

Arthur Dracup becomes Arthur Smith

Two facts substantiate this claim:

First, the 1939 Register includes a man called Arthur Smith, resident in Coventry, with a date of birth exactly a year before Arthur Dracup’s – 10 January 1893 instead of 10 January 1894.

He was lodging with a couple called John and Emma Lycett at ‘4 in court 2’, which was in Henry Street, Coventry. Both men were described as ‘Salesman Fruit’, while Emma was described as ‘Saleswoman Florist’.

The layout of the roads has changed since 1939, but the rump of Henry Street remains, close to Coventry Canal Basin. This contemporary map shows how it looked in 1939. One suspects that they were living in or next to their warehouse.

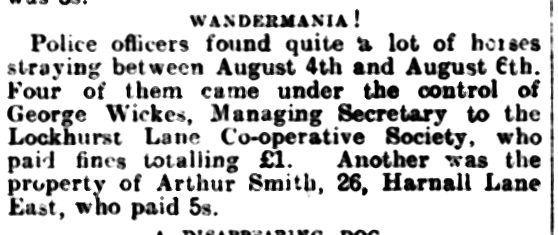

Second, there are multiple references in Coventry newspapers to this ‘Arthur Smith’, a hawker with a horse and cart, describing his frequent brushes with the law.

Prior to 1930, the address given for him is invariably 26 Harnall Lane East, Coventry. Thereafter it becomes 32 Harnall Lane East. These were the addresses of his sister Bertha Chattaway, her husband and family. They were a few hundred yards away from, Henry Street.

Perhaps Arthur normally lived with his sister, the 1939 Register entry being only a temporary arrangement. Or perhaps he gave his sister’s address when charged, because he moved his home address too often to be sure of receiving important mail.

According to the local papers, an Arthur Smith of 26 Harnall Lane East was fined for allowing his horse to stray as early as October 1923, then again in December 1923, May 1924 and August 1925.

In 1928 he had a similar case dismissed because he was in Birmingham on the day he was alleged to have been over 20 yards from a horse and float for which he was assumed responsible.

Using the 32 Harnall Lane East address, he paid another fine for allowing his horse to stray in June 1930, and yet another in April 1932.

In May that year he was charged with being drunk and disorderly, and in October:

‘A hawker, Arthur Smith, 32 Harnall Lane, who was charged with using obscene language to the annoyance of passers-by in Bishop Street yesterday, was fined 20s.

PC Mason said the prisoner was engaged in a quarrel with a number of other men, and when spoken to by witness became very abusive.’

In January 1933, he was fined 10s for not having lights on his horse and dray and going too far away from it while hawking in another street.

Then there was a hiatus until the final year of his life.

The Royal Leamington Spa Courier and Warwickshire Standard of 4 August 1939 reported:

‘Hawker Summoned for Shouting

“These people come out from Coventry and shout in the streets, and, when we have complaints from residents, we have to take proceedings” said Inspector Perrott, when Arthur Smith, of 32, Harnall Lane East, Coventry, was summoned for shouting for the purpose of hawking to the annoyance of residents on July 1st. PC Spencer said that when in the police station he heard the defendant shouting, so he went out and cautioned him. He later received a complaint as to a man shouting in School Lane, and when he went there found it was the defendant. When told he would be summoned, defendant said “We always shout where I come from.” A fine of £1 was imposed, there having been a previous conviction for a like offence’.

In September 1939, he and two other men were alleged to have stolen two sacks of potatoes. They claimed it was a mistake and the case was dismissed.

Finally, in March 1940, he was again fined £1 for being drunk and disorderly. The offence took place in Castle Street. Inspector Ward said of Arthur:

‘He has been in trouble for this kind of offence for eight years.’

So, in 1922 or 1923, Arthur had decided to follow two of his sisters to Coventry, and to live there under an assumed name.

He must have wanted to escape from his life in Bradford. Perhaps he felt that his cards were marked there, or that there was nothing left to keep him in Yorkshire, or perhaps he simply thought that he could make a better living in the Midlands.

But the fact that he dropped his surname for ‘Smith’ suggests that he didn’t want to be traced, whether by the police, the authorities or his estranged wife.

Two fatalities

Back in March 1924, Arthur Dracup/Smith was involved in a collision that caused the death of a motorcyclist, James Leonard Gibbins:

‘Arthur Smith, Harnall Lane East, stated that at about 7.45 on Tuesday night he left Kenilworth, driving a pony and trap. When about a hundred yards from the two miles post from Coventry he saw a motor cycle proceeding from Coventry on the wrong side of the road. Witness had a good candle lamp burning, and there was also a light on the motor cycle. He (witness) said to a friend in the cart “Hello, where is he coming to?” The cyclist came on and ran straight into the horse’s chest. The animal fell down on to its knees, witness was thrown out on to the horse and then to the ground, while deceased lay partly on the grass and partly on the road. The near wheel of the trap was practically touching the grass on the left hand or proper side of the road.

Sidney Lloyd, Munition Cottages, who was in the cart, said he just looked in time to see deceased run straight between the horse’s legs. The animal fell on to its knees, and was twisted right round in the shafts; it was badly cut in the chest.

Sergt. Manlove, who was called to the scene of the accident said deceased had been taken to the Hospital on his arrival. The motor cycle had been placed in the ditch, but the place of contact was shown by a quantity of petrol in the road. This was two feet from the right hand side of the road proceeding into Coventry. There was a skid mark 12 feet long, which ended where the petrol was, and witness thought that probably deceased saw the cart too late to avoid the collision, although jamming on his brakes. The number plate of the cycle was bent over and there were horse hairs on the plate. There was no doubt the front wheel went between the horse’s legs and the animal was cut by the number plate. There was no reason why deceased should not have seen the cart, as the accident happened on what was known as the “straight mile”.

Dr McClure said Gibbins was dead on arrival at the Hospital. The chief injury consisted of the fracture of the upper four ribs on the right side. Death was due to heart failure, there being direct injury to the heart.

Returning a verdict of “Accidental death”, the Coroner said it was a most extraordinary case. If there was any negligence deceased seemed to have been guilty of it. There was no question that there was any negligence on the part of Smith or Lloyd, Neither of them was in any way to blame.’

Gibbins was only 34. He left a widow and two small children. He had been riding a Triumph; coincidentally Arthur’s brother-in-law James Chattaway worked as a motor cycle packer for Triumph.

One wonders about the impact of this accident on Arthur. Did he have any cause to blame himself, despite the evidence given to the police and the Coroner?

When Arthur himself died, sixteen years later, on 5 July 1940, aged 46, he was once more recorded as living with his widowed sister Bertha Chattaway at 32 Harnall Lane East in Coventry. The death was registered under his correct name. The cause of death was Broncho-pneumonia

His employment was recorded as ‘Fruiterer (Master)’. I take this to mean that he employed an assistant, rather than that he was a Master Fruiterer.

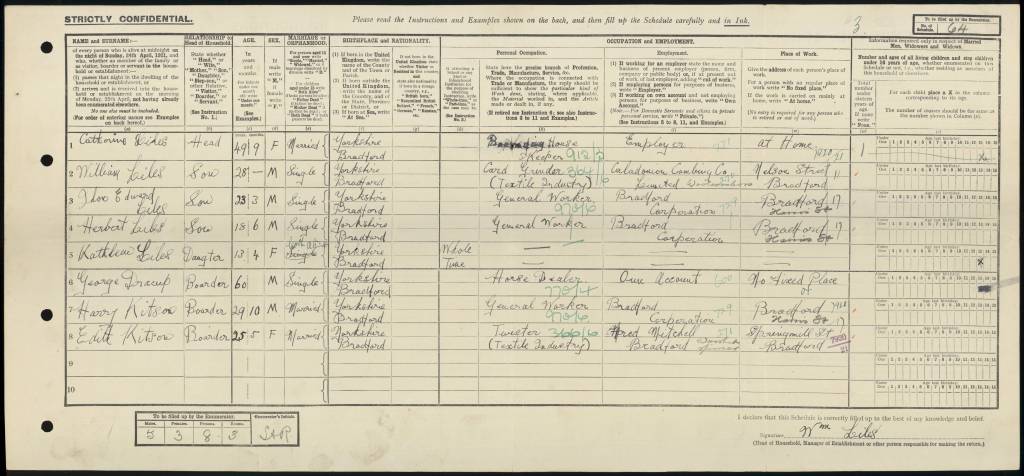

George Dracup (1860-1926) and Mary Jane, nee Holmes

George was 11 in 1871, but already employed as a worsted spinner.

He married Mary Jane Holmes on 3 November 1878 when they were both aged 19. She was a worsted stuff weaver, daughter of Thomas Holmes, an overlooker and Jane, nee Marshall.

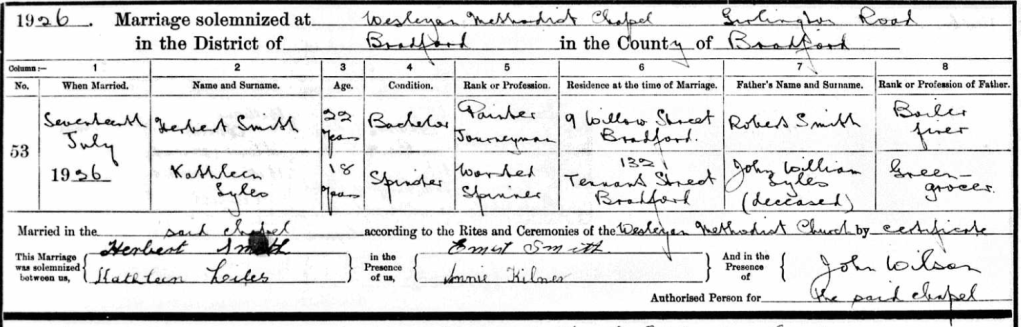

At the time of his marriage George was employed as a soap boiler and was living at 19 Copley Street in Horton. Mary signed her name, but George could only leave his mark, so he may also have been illiterate.