In June 2023 we resumed our progress along the Coast Path, this time basing ourselves in Salcombe for the week.

We were starting from the ferry crossing at Plymouth’s Mount Batten Point, having completed the stretch from Par in March, and were aiming to reach Torcross.

This we achieved, with the following schedule:

- Day 1 (Saturday): Mount Batten Point to Warren Point (River Yealm) (7.5m)

- Day 2 (Sunday): Noss Mayo to Mothecombe (River Erme) (9.1m)

- Day 3 (Monday): Wonwell to Hope Cove (9.6m)

- Day 4 (Tuesday): Hope Cove to Salcombe (8.1m)

- Day 5 (Wednesday): Salcombe to Torcross (12.6m)

- Day 6 (Thursday): Rest day

According to the distance calculator we completed a further 46.9 miles. We have now walked a total of 465.0 miles from Minehead, leaving 164.6 miles outstanding. So we’re almost at three-quarters distance!

Some of these daily distances may look underwhelming, but this section includes several stretches judged ‘strenuous’, so were pleased with our progress.

There are several estuaries too, which complicate the logistics. Though we completed all the ferry crossings, we didn’t wade across the Erme (where there is no ferry), but ended on one side and started the following day on the other.

Tracy, who is a stickler for the rules, judged this acceptable.

The weather was almost entirely rain-free throughout, with frequent sunny spells and temperatures typically in the low twenties.

Salcombe

The journey to Salcombe was straightforward: we caught an extremely busy 11:03 GWR service from London Paddington, arriving in Totnes at 13:47. From there, we picked up a Tally Ho 164 bus service via Kingsbridge, arriving at Salcombe at 15:03.

We came to rely on this service on several occasions during the week, getting to recognise the different drivers, invariably friendly and helpful, despite complaining constantly (and with justification) about their excessively long shifts.

It was but a short walk to our home for the week – Blueboat Cottage, at 23 Island Street. We found this initially on Air’B’n’B, but chose to book it directly as that was slightly cheaper.

But nothing is cheap in Salcombe, so we still had to fork out £805 for the week, plus a refundable damages deposit.

Our location was very convenient, just a few minutes’ walk from the town’s main street – Fore Street – in one direction, and a few minutes from the Co-op and the bus stop in the other.

It was a small, two bedroomed cottage, the middle house in a row of three built side on to Island Street. There was a small shared area outside, equipped with a patio table and two chairs.

Inside, it was open plan downstairs, the living area to the front and the kitchen to the rear; upstairs, a double front bedroom barely wide enough for the bed, a back bedroom holding two single bunks and a small shower room.

It would have been a tight squeeze for a family of four, but it was perfect for a couple.

I found Salcombe rather an odd place. The setting is astonishingly beautiful, although the harbour is crowded with yachts and cabin cruisers. The shops, pubs and eateries are largely confined to the roads adjacent to the harbour, including several listed buildings, but residential streets extend some distance inland and uphill.

Salcombe has evolved to service a sizeable cadre of wealthy second home owners, and their almost as wealthy offspring, who come to party and/or mess around in boats.

We witnessed a distasteful sense of moneyed entitlement, even arrogance, amongst some of these younger non-resident incomers.

The first record of Salcombe dates from the Thirteenth Century. It was attacked by a French raiding party in 1403 and what later became Fort Charles was built nearby during the reign of Henry VIII. The Fort was besieged by Parliamentarians in 1646 until the Royalist Garrison finally surrendered.

Salcombe dates its first holiday home to 1764 though, by the beginning of the Nineteenth Century, it was establishing a reputation as a shipbuilding centre.

It also acquired prominence in the fruit trade, deploying fast schooners to import oranges and lemons from Spain and the Azores, even pineapples from the West Indies.

By 1850 the population had reached 1500. But, as schooners gave way to steam power, prosperity began to decline.

Tourism took hold once the railway reached Kingsbridge in 1893. Around the same time, Salcombe became popular with the yachting fraternity. It began to attract a steady flow of rich men seeking either summer homes or retirement properties.

This ‘gentrification’ was rudely interrupted by the Second World War, when Salcombe suffered at the hands of the Luftwaffe. It also hosted part of the force that landed on Utah Beach during the Normandy Landings.

In recent years the invasion of second home owners has become all but overwhelming. The permanent population, about 2,000 strong, multiplies at least twelvefold in the summer months.

By 2022, the average house price had reached £1.2m and Salcombe had become the most expensive seaside town in Britain. Precious few Devonians can afford to live here.

After unpacking, we headed to the Co-op which, apart from a SPAR convenience store inland, is the only food shop of any size in the vicinity. The prices were noticeably high, even for Londoners like us.

Afterwards we walked along Fore Street, admiring the sights, before heading to the Ferry Inn from where we could compare the ferryman of today with his predecessor, depicted on the pub’s sign.

We shared the terrace with two huge sprawling, slobbering Great Danes.

That evening we collected a pre-ordered fish and chip supper from the Crabshed, which we carried back to our cottage, braving the marauding seagulls. The serving of mushy peas was miniscule, but the quality was otherwise very good.

We slept with the window open, just behind our heads – it was too warm to do otherwise – despite the seagulls mewling until well after dark and resuming at first light. My sleep was fitful, to say the least.

Salcombe does seem to have let its seagull population get a little out of control.

Day 1: Mountbatten Point to Warren Point

We faced a marathon bus journey to reach Mount Batten Point. There were essentially two options: two buses into central Plymouth and a ferry across, or three buses direct to Mount Batten.

We opted for the latter. This involved catching: the 164 up to Totnes; a Stagecoach ‘Gold’ service from there to the outskirts of Plymouth; and a Stagecoach 2 service to Mount Batten Point.

We departed Salcombe at 07:10 but were soon travelling at snail’s pace behind an oblivious jogger with headphones! However we made it to Totnes on time, though Google Maps was confused about which stop we needed. Luckily, we chose the right one.

We had the front seats upstairs on the Gold service, which runs across country through Ivybridge and the rather soulless new town of Sherford. A small but precocious girl sustained a permanent prattling on the seats adjacent.

The full journey took almost two-and-a-half hours. Arriving at our destination, we made haste to use the convenient toilet facilities. While adjusting our backpacks, we exchanged ‘good mornings’ with a rather down-at-heel individual who had been camping. His dog was tottering – almost literally on its last legs, perhaps.

HMS Searcher, a Border Force vessel, was leaving the Harbour as we set out, while several yachts seemed to be racing just off the breakwater.

Soon we were passing Mount Batten Tower, a circular artillery fort built here in 1652. It has recently been renovated and is now available as a wedding venue.

Making our way round Batten Bay, past the massed ranks of benches, we soon hove to at the Jennycliff Café, urgently in need of a proper breakfast.

Two sausage sandwiches and black Americanos later, we resumed, passing through woodland to seaward of Staddon Heights Golf Club.

Somewhere in this vicinity we passed a blue coast path milepost claiming that we had only 175-and-a-half miles left to Poole. This is completely inaccurate, though it had us fooled for a while.

We passed some aerials and concrete, surrounded by forbidding barbed wire. A notice said access was no longer permitted owing to the damage caused to what is, presumably, a military facility.

Then we descended to the Staddon Point Battery, Fort Bovisand and Bovisand Harbour. The Fort was constructed here from 1861 to 1869, the Battery preceding it in 1845. Both were intended to defend Plymouth Sound. The fort is arc-shaped and originally housed 23 guns.

We stopped at Bovisand Beach for a drink and a short rest, noticing for the first time, the small red-and-white-striped Staddon Point Lighthouse, perched just round from the Fort.

Behind the beach, Bovisland Lodge Holiday Park stretches back along the valley.

Leaving the Beach, there is a steep climb up to a second tranche of chalets. I was blissfully storming up when I noticed that I’d left Tracy behind.

I discovered her chatting to an elderly gentleman who had recently constructed a driftwood sculpture on the beach which he was monitoring for graffiti and vandalism.

He was pleased with our interest and it was with some difficulty that we parted, continuing on our way, past several more agglomerations of chalets, before they finally vanished above Crownhill Bay.

We noticed a marker for ships at sea, seemingly adrift in its own sea of bushes, before reaching the rocky promontory at Renney Point. A white egret was wading on the shore, but swiftly took flight.

Soon we were abreast of the Great Mew Stone off Wembury Point, purchased by the National Trust in 2006. It had been owned previously by the Ministry of Defence, forming part of HMS Cambridge, a shore establishment on Wembury Point (because it was in the line of fire).

Cambridge has since been completely demolished.

The Mew Stone was formerly inhabited. A local criminal was allegedly ‘transported’ there for seven years in 1744, accompanied by his family.

A subsequent occupant, one Samuel Wakeham, provided boat excursions from Wembury Beach and kept pigs and chickens – while also pursuing a lucrative sideline in smuggling.

And JMW Turner painted it a few times.

We stopped briefly to return a scarf to a woman walking just in front who, we guessed from her carefully co-ordinated colour scheme, had dropped it. We were right!

Soon we could see St Werburgh’s Church high above Wembury Beach, and thought we must be close to our destination.

We passed a bench commemorating Trooper Joshua Hammond, aged 18, from Plymouth, who was killed in Afghanistan. It was bedecked with a fresh wreath of poppies.

Wembury itself lies back from the beach, behind St Werburgh’s, whose tower dates from the 14th Century; the remainder from the 15th and 16th Centuries, but with Victorian restoration.

It contains a monument to Sir John Hele MP (c.1541-1608) who built a splendid manor house here, since demolished.

John Galsworthy (1867-1933) visited in 1912 to research his family history. This experience later informed a similar expedition by Soames Forsyte.

The Beach looked inviting, with a fair few paddlers, and the Old Mill Café might have supplied an iced coffee, but a handy signpost said we had another 40 minutes’ walking to reach the ferry station at Warren Point.

We realised that, unfortunately, we were pressed for time, since the last (only?) bus departed Noss Mayo at 14:05. The remainder of the walk had relatively little to commend it, other than occasional views of the estuary below.

The geography is complex hereabouts, since the River Yealm turns sharply north, inland, although a tributary, Newton Creek, stretches east between Noss Mayo to the south and Newton Ferrers on the northern bank. The Yealm is a relatively short river, rising on Dartmoor.

We reached the ferry station at about 13:20, well inside the projected 40 minutes. Bill, the extremely helpful ferryman, advised us to speak to bus driver Phil about our connections back to Salcombe. He dropped us near the old cellars, just below Passage Road, about a ten-minute walk into Noss Mayo.

We had been unable to eat our sandwiches, given the pressure to reach the ferry on time, so we polished them off on a bench to the rear of the playing fields.

At the bus stop we chatted to a fellow walker who had come from central Plymouth that morning and who we had seen earlier, asking for water at the Jennycliff Café. He looked a little tubby, but he was happily reeling off a succession of 16- and 17-mile days, so one should never judge by appearances!

Phil had Paul Gambaccini blaring out for the pleasure of his assorted customers, as he piloted his Number 94 Tally Ho service towards the point on the A139 from whence a Stageoach Number 3 returned us to Kingsbridge.

Here we picked up the 164 back to Salcombe, our sixth bus of the day.

The incoming driver of this service was contemplating having to continue his shift because his replacement hadn’t shown up, but eventually she came strolling round the corner while her bus-full of passengers waited patiently. Cue much gentle ribbing by all concerned.

Arriving back in Salcombe, we visited the Kings Arms for a pint. Sadly, they had run out of the Salcombe Brewery offering, so I was restricted to Pravha.

We sat outside, watching a tableful of increasingly drunken twenty-somethings dressed as pirates. One was already taking on water rather than beer and looked unlikely to last the afternoon.

On returning to the cottage I felt the need for a siesta, given the beer and my disturbed sleep the preceding night. I decided to remove the duvet for extra coolness, discovering as I did so that it was 10.5 togs. No wonder I’d been hot!

We dined in and retired early.

Day 2: Noss Mayo to Mothecombe

It being Sunday, we knew there would be negligible public transport.

But our research indicated that there was no day on which we could get to Noss Mayo in the morning by bus, so a taxi was our only alternative. And, being Sunday, taxis were operating at a premium ‘tariff 2’ rate, so we resigned ourselves to the journey costing an arm and a leg.

We arranged for Roger of Clark Cars to collect us outside Salcombe Co-op at 09:00. By the time he dropped us in Noss Mayo’s tidal car cark some 40 minutes later, we owed him over £100.

Our official guide suggested that the second half of our day would be strenuous, and it would take us approximately five-and-three-quarter hours to walk the full distance. Allowing for even slower progress, we asked Roger to pick us up from Mothecombe at 16:30.

This morning was cooler and more overcast than Saturday, but conditions were ideal for walking.

We retraced our steps out of the Village, down Passage Road, past the ferry landing point and on along the southern side of the Yealm Estuary.

Noss Mayo was first documented in 1286 as Nesse Matheu, the manor belonging to a certain Matheu at this time. Newton Ferrers, opposite, was given its name by Ralph Ferrers, who held it around 1160 AD.

Edward Baring, of the prominent banking family, purchased the estate at nearby Membland in 1877 and was created the first Baron Revelstoke of Membland.

He oversaw extensive building in the area, including St Peter’s Church in Noss Mayo. But, facing financial difficulties, he sold up at the close of the Nineteenth Century, and his manor house, called Membland Hall, was later demolished.

We followed the path into woodland, above Cellar Beach. A lady coming in the opposite direction complained that the dog tagging along behind did not belong to her.

We were soon on our way around the prominent headland, jutting out at Gara Point, but never too far from Noss Mayo. The path was wide and well made since we were following Revelstoke Drive, a nine-mile carriage-way which Lord Revelstoke had laid for the entertainment of his guests.

Towards the end, we realised that beneath us sat several green-painted caravans, an intervening band of trees shielding them from view. This turned out to be Revelstoke Park, above Stoke Beach.

The caravans share this space with the ruined Church of St Peter the Poor Fisherman, parts of which are Thirteenth Century. It suffered storm damage in 1840 and fell further into disrepair once St Peter’s was built in Noss Mayo.

It contains the grave of Rupert Baring, a child of Lord Revelstoke’s who died in infancy. Another of Revelstoke’s sons was the novelist Maurice Baring (1874-1945).

We didn’t bother descending to inspect the ruins at close quarters, but continued above, along a more remote and picturesque section, with rocky foreshores below.

Eventually we passed the prominent St Anchorite’s Rock, just above St Anchorite’s Cove. I couldn’t discover the derivation of this name, though it seems a fairly recent invention.

Lunch was taken while perched precariously just above Butchers Cove, and was disturbed by a few spots of rain.

We could already see Burgh Island in the middle distance, and it wasn’t too long before we were looking down on the sandy expanse of the Erme Estuary. Like the Yealm, the Erme originates on Dartmoor. Strictly speaking, the estuary is a ria – a drowned river valley – containing large areas of mud and salt marsh.

From far away it looks relatively straightforward to cross but, once on the bank, one can discern a relatively narrow channel of fast-running water in the middle of the muddy sands.

The guidelines say it is possible to wade across in knee-deep water between the slipways, but only one hour either side of low tide. We had arrived maybe half an hour too late, so decided it made sense to stop here, as we had previously planned.

As our ferrywoman on the Avon (see below) later remarked: you wouldn’t want to get stuck in the mud on an incoming tide and have to wait for the RNLI to dig you out!

However, we were still comparatively fresh, having completed the walk in some five hours, not finding it particularly strenuous. We would have a couple of hours to kill until Roger arrived.

This we spent in the Schoolhouse, a café slightly inland, close to Mothecombe Gardens. We enjoyed its laid-back ambience and were happily ensconced when Roger arrived, our return trip costing only slightly less than the morning’s outward journey.

We dined in again, and I had a rather better night’s sleep.

Day 3: Wonwell Beach to Hope Cove

Tracy’s ruling meant that we didn’t have to wait for low tide again to cross the beach from the Mothecombe side, so we could recommence above the Wonwell Beach slipway on the Salcombe side of the Yealm.

Even so, there were still no buses, so we had to hire another taxi for the outward journey. Roger was already booked for a trip to Exeter Airport so, after an extensive ring-around, we finally secured Taxi Mike, who told us about his sideline as a food blogger.

He wouldn’t take us along the narrow road from Great Torr to the Beach, apparently because of the traumatic memory of being stuck there several years previously, but we were happy to walk the extra mile or so to down to the Estuary.

It was another cool, fresh morning, but grew progressively warmer as the cloud burned away.

On this occasion, Tracy’s official guide said we might need some two-and-three-quarter hours to walk to Hope Cove – which must have been a misprint since it took us almost twice as long!

The tide was much further in at this early hour, but did not encroach on that small part of Wonwell Beach that we still had to cross, south of Malthouse Point.

Climbing up on to the Beacon, we could see Burgh Island much closer now, as a field of sheep posed in the foreground.

The view across Gutterslide Beach and the Meddrick Rocks was particularly splendid, as the sun danced on the tiny wavelets below.

By 11:30 we had descended steeply down to Wyscombe Beach, where a herd of bullocks (thankfully fenced in) stood to greet us. There is a derelict building here that would make a perfect café, but sadly it remains derelict.

Climbing up towards Toby’s Point, Burgh Island was now just below us, beneath a stretch of cow parsley. We passed the big holiday camp at Challabrough then skirted round the edge of Bigbury-on-Sea to find the toilets.

Bigbury-on-Sea itself is a tourist village: almost two-thirds of its properties are second homes or holiday rentals.

Burgh Island, just offshore, might once have housed a monastery, the surviving Pilchard Inn possibly having been its guest quarters.

The white rectangle of Burgh Island Hotel is built slightly higher, constructed in the late 1920s by Archibald Nettlefold in art deco style. He ran the Nettlefold Studios in Walton-on-Thames, which produced silent films and early talkies.

The Hotel is closely associated with Agatha Christie (1890-1976), since the setting inspired the locations of ‘And Then There Were None’ (1939) and ‘Evil Under the Sun’ (1941). Christie herself was a regular visitor.

It is also well-known for the sea tractor which transports visitors across to the Island at high tide.

We climbed down on to the beach to eat our lunch, Burgh Island to our right and a vast empty stretch of sand to our left. This is the largest sandy beach in South Devon: RNLI flags marked out the relatively narrow stretch where it was safe to swim or surf.

The tide was out, so the sea tractor was resting. A small yacht was beached just off Burgh Island, awaiting the return of the waves.

We had a brief paddle before departing on our way, following the path through overflow car parking up the deceptively steep Folly Hill. We had pinpointed a possible café up here, but it seemed to have closed at midday. What is the point of that?

We worked our way steadily back down to Cockleridge Point, to the place from where one hails the ferry across the Avon. It was a beautiful spot, the serpentine river writhing seawards through sparkling sand and patches of vivid green weeds.

(Incidentally, this is the Devon Avon, which rises in Dartmoor, not to be confused with the other, far bigger one.)

We had arrived a little before 14:00, when the ferry resumed, so were waiting before ringing the bell and shouting, as the instructions instructed. I suggested that Tracy’s higher voice might carry better over the River, and that she should bellow ‘Ahoy’!

However, the ferry resumed from the other side, bringing passengers across, and the ferrywoman hailed us instead. She asked us to walk further down the beach where she could drop off her passengers, opposite Jenkins Boathouse.

As she took us across, she related some of the history of the area, which I have embellished below.

The ferry crosses to Bantham, once a pilchard fishing centre. In 1922, the entire village and 750 acres of land was purchased by one Lieutenant Commander Charles Evans. His family then controlled the estate until 2014.

Thatched Jenkins Boathouse probably dates from the Eighteenth Century but was extensively renovated in the early Twentieth. Evans built the Coronation Boathouse in 1938, to celebrate the coronation of George VI.

When the Evans family put the estate up for sale, for £11m, it was bought by a private individual – Nicholas Johnston – who outbid the National Trust. An old Etonian, he also owns the Great Tew Estate in Oxfordshire and has a major interest in several quarrying companies besides.

It’s fair to say that Johnston hasn’t always seen eye to eye with the local council’s planning committee. The current Estate Management Plan (2021-2034) is available online.

On reaching the Coronation Boathouse, we had to exit the slipway via temporary steps and bridge, before heading west of Bantham, towards the headland on the Estuary’s south coast.

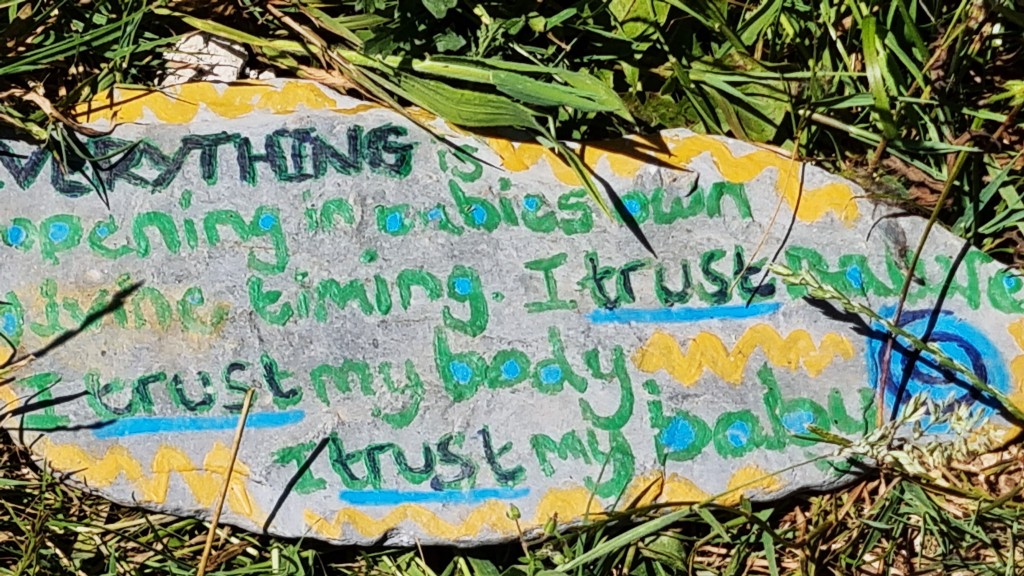

Close to Bantham Beach, we found Gastrobus, which finally supplied me some much-needed coffee, and chocolate brownie besides. Tracy was glancing uneasily at a sign nearby.

So we were very careful to stick to the paths and found only this message stone.

Descending again, beside Thurlestone Golf Course, we passed two or three sandy coves. This one seemed to hold a naked couple under a small white umbrella!

Instantly, though, our attention was diverted by a kestrel performing incredible aerobatics within just a few metres of us. I caught this on video, ignoring the golfers behind me – they would just have to wait.

Continuing on to Thurlestone Beach, we stopped for a more extensive paddle. The place takes its name from Thurlestone Rock, an arch just a little way offshore (a thirl stone was a stone with a hole in it).

As we watched, a kitesurfer on a hydrofoil launched himself across the bay, making one spectacular pass just in front of the Rock, only to come to grief almost immediately afterwards. It took him a long time to make his way back to shore.

Newly refreshed, we passed behind the beach into a boarded, marshy area, emerging near a herd of cattle resembling water buffalo. I don’t think it was a mirage! Then we stopped again briefly at the Beach House for rather expensive ice creams.

Resuming, after a visit to the toilets adjacent, we climbed over the last hill between Thurlestone and Hope Cove, passing through Outer Hope first then, on the other side of a small headland, Inner Hope.

Tired now, and needing shade in which to recuperate, we headed for a concrete bench next to the old lifeboat house, built here in 1878. People were swimming from the concrete slipway.

Our 162 Tally Ho bus arrived on time, the female driver advising us to change to the 164 in Marlborough rather than on the busy main road suggested by Google Maps.

This we did, arriving back in Salcombe just in time to prepare ourselves for dinner on the terrace at Dick and Wills, which looks out over the waterfront.

It was a delicious meal, though expensive, and we had to wait an inordinately long time for the main course, listening all the while to the effortlessly vacuous small talk of the wealthy patrons around us.

Day 4: Hope Cove to Salcombe

We had reached that day in our schedule we always appreciate, when the walk ends in the place we are based!

We successfully negotiated the previous evening’s buses in reverse, spending an interval of 20 minutes or so sitting on a bench next to Marlborough’s post office, watching the morning’s comings and goings. We chatted to a young woman who worked in Hope’s post office, and who relied on this service to get her there on time.

We arrived at Hope Cove at 09:15. On the way out, we saw enticing adverts for a café a little further ahead, at Bolberry, but they didn’t mention it was closed on Tuesdays.

Not for the first time, our walk began by rounding a headland – this time Bolt Tail, which juts out beneath Hope Cove. It hosts another in the string of Iron Age promontary forts built along this coast.

The cloud began to break as we looked back over Hope Cove and Thurlestone, giving some beautiful light effects. We stopped to take the photograph of a couple who were struggling to operate their selfie stick.

By the time we reached Soar Cove, the cloud had rereated to the horizon and the light playing on the beach made vivid colour contrasts. We thought this quite possibly the most beautiful location we have encountered so far!

And we couldn’t resist another paddle.

A young mum turned cartwheels at the water’s edge, to entertain her toddler. Meanwhile, a group of ladies we’d seen swimming at Hope Cove the previous evening arrived beside us for another session.

Reluctantly departing this idyllic setting, we continued on towards Bolt Head, where someone stood atop the rocky outcrop, silhouetted against the sky. The number of strollers increased significantly, just as we were seeking urgent toilet stops.

Heading on, round Starehole Bay, the Kingsbridge Estuary came into sight, stretching back inland past Salcombe on its western side. A bench with a view was available, so we chose this spot for our lunch.

Shortly afterwards, we came upon a scenic memorial to the Salcombe Lifeboat Disaster of 27 October 1916, when thirteen of the crew were lost as the boat capsized on Salcombe Bar. The average age of the crew was 40, since many of the younger men were away fighting in the Great War. Only two men survived.

They were attempting to rescue the crew of a wrecked schooner, Western Lass, unaware that they had already been brought ashore.

There is a matching memorial on the other side of the Estuary.

Descending to South Sands Beach, we refreshed ourselves with iced coffees (tinned) from Bo’s Beach Café. We amused ourselves watching the South Sands Ferry docking with its beach tractor in the shallows.

Then we had a cooling paddle before climbing up the surprisingly steep hill between here and North Sands Beach, where we decided, spontaneously, to stop for afternoon tea at the Winking Prawn.

We caused problems by entering the wrong way and thinking we had to order at the counter rather than being waited upon. But it was refreshing to be surrounded by real people, rather than the wealthier patrons of inner Salcombe establishments.

This leg concluded at the ferry crossing to East Portlemouth, beside the Ferry Inn, but we delayed our celebration, returning instead to our cottage.

Later that evening we dined on the terrace at the Fortescue Inn. A giant seagull watched us, gimlet-eyed, from the low-hanging roof, threatening to swoop at any moment.

It had taken a while for Tracy to place the order, since the bar staff had become overwhelmed while trying to resolve a problem with one of the food orders. As we departed, an arrogant man behind us was still complaining.

Day 5: Salcombe to Torcross

We also appreciate the day on which no outward journey is required. We were down on the riverfront in time for the first ferry over to East Portlemouth, at 08:30. I particularly enjoy getting underway early, while the air is still fresh and clean.

While waiting for the boat, we chatted to a couple of young walkers still at university – one at Bristol, the other at Ruskin College, Oxford – who were planning to reach Stoke Fleming, several miles further than Torcross. The only other passengers were two 16 year-old girls who seemed to be anticipating a day on the beach at Sunny Cove.

The youthful walkers disappeared while we were still preparing for departure from East Portlemouth, but we did see them once later. Indeed, we made rapid progress in the first half of the morning since, once again, there were no coffee stops in prospect.

From the ferry, one passes a series of sandy coves on the way up to Portlemouth Down on the headland. We noticed signs saying that the largest, Mill Bay, had been affected by a recent sewage spill.

East Portlemouth was once a port and shipbuilding centre but is now best known for its holiday homes, two of which are said to belong to Kate Bush and Michael Parkinson respectively.

On the approaches to Gammon Head, we came across a plaque recording that the headland was given to the National Trust by the Rose family in 1965.

There is a porky theme to this section since one passes, in rapid succession, Pig’s Nose, Ham Stone and Gammon Head. I spent some time trying to discern piggish features amongst the various rock formations.

Shortly after 10:30 we reached the Coastwatch lookout station on Prawle Point, the southernmost spot in Devon, and stopped to explore the informative visitors’ centre.

A little further on we passed in front of a line of coastguard cottages, remarking, as we did so, the peculiarity of the landscape, for green fields stretch seawards below the line of cliffs.

A herd of dark brown cows posed in the foreground, the sea sparkling just behind them.

We were now tiring, on our fifth continuous walking day, and were pleased to find a bench with a scenic view, just past imposing Maelcombe House, owned by a wealthy company director.

We soon stopped again, for a paddle and early lunch on Lannacombe Beach, backed by a converted limekiln and watermill. It was almost deserted, save for a couple and their dog.

We met many more people afterwards, on the approaches to Start Point. A few dozen could be seen on Mattiscombe Sands, with its amazing ‘twin peaks’ rock formation.

Soon we were closing on the lighthouse. The 28-metre tower was completed in 1836 and converted to electricity in 1959. The light now has a range of 25 nautical miles. There have been many shipwrecks here: in March 1891, two ships were lost within twelve hours, costing over fifty lives.

As we passed by, we wondered aloud why we hadn’t chosen to stop at this point, since the official guide concludes a leg here. The answer is straightforward: there is no public transport connection.

In the car park I was overjoyed to find a horsebox selling coffee and cake. ‘The first coffee for 10 miles’ I exclaimed excitedly, frightening the barista in the process.

But, seriously, Devon is not a patch on Cornwall for coffee stops!

We sat on the bank here for half an hour, savouring our coffee and brownie while admiring the new prospect opened up to our view, on the eastern side of Start Point. For the nature of the coastline is markedly different to what had gone before.

Much refreshed, we headed downhill, through the fields towards Hallsands.

The southern part of Hallsands is no more, having been gradually submerged following gales and high tides in January 1917. One cause was probably extensive offshore dredging, undertaken twenty years previously, to supply sand and gravel to expand the naval dockyards at Plymouth.

Ironically, the viewing platform, built over the site of the submerged village, has now been permanently closed owing to coastal erosion. The details on the now inaccessible boards are preserved here.

The next settlement is Beesands, which stretches along a single road, running parallel with the beach. It is said that the Cricket Inn hosted the first public performance by Jagger and Richards, the Richards family holidaying frequently here during the 1950s.

We followed the misleading signs at the end of the beach, and ended up in a bird hide on the wrong side of the small freshwater lake, which is called Beesands Ley.

On correcting our mistake, we discovered the sting in the tale of our walking programme: a stiff and extended climb through woodland and quarry workings, before the final descent to the straight shingle beach at Torcross.

Torcross marks the southern end of Slapton Sands, which runs north-eastwards, between Start Bay and the freshwater lake of Slapton Ley behind – a much larger scale version of the landscape at Beesands.

The entire stretch, which carries the main road between Kingsbridge and Dartmouth, is particularly vulnerable to coastal erosion and rising sea levels.

Torcross seemed a little underwhelming, perhaps, but we found a café selling ice creams and made our way on to the beach, running the gauntlet of a school field trip. We just had time for a final celebratory paddle.

The Stagecoach 93 bus returned us to Kingsbridge, from which we caught the trusty 164 back to Salcombe.

That night we had pizza with wine at home.

Rest Day

We were in no hurry to get up on the following morning, but finally made it to Salcombe Coffee Company for breakfast. We had doorstep sandwiches – sausage for me; bacon and egg for Tracy – washed down with pleasantly strong black Americanos.

Then we climbed on board the South Sands Ferry, to experience directly the docking with the sea tractor we had previously witnessed from South Sands Beach. It was going to be a hot, sunny day.

We had decided to visit Overbecks, a National Trust garden belonging to a house called Sharpitor, just above South Sands.

From 1913, the house was owned by a Mr and Mrs Vereker, who extended the gardens significantly. Their second son was killed at Mons in 1914 and, in memory of him, they offered Sharpitor to the Red Cross Society as a convalescent home for injured troops.

Then, in 1928, it was sold to Otto Overbeck, an inventor who patented an ‘electrical rejuvenator’. This might have been employed by an elderly couple – probably in their mid-70s – who decided to race us up the steep climb to the house. They both seemed as mad as a box of frogs.

Feeling mischievous and honed to climbing fitness after five days on the coast path, we pressed them all the way to the top. But the lady stopped on the final haul, enabling us to overtake. They never spoke.

After an enjoyable walk around the gardens, we descended once more to the beach.

We’d been intending to have a cooling swim but, despite the heat of the day, the water still felt very cold, so we contented ourselves with further paddling.

We watched two children, 11 or so, get into serious trouble with their parents for taking their paddle boards out too far and for too long: we couldn’t quite understand why they weren’t in school.

We walked back into central Salcombe, picking up ice creams at Salcombe Dairy and buying three tiny carved wooden mice as a small gift for my son. Then it was back to the cottage to pack.

That evening we took the 164 bus out to Kingsbridge and walked round the quay and the Town.

Kingsbridge is the most substantial settlement in the South Hams district, lying at the head of the Estuary, or at least one of the two forks. It was established around a bridge linking two early medieval royal estates, later expanding to incorporate the neighbouring settlement of Dodbrooke.

The most notable resident was William Cookworthy (1705-1780) who discovered china clay and was the first manufacturer of English porcelain. Anthony Trollope later used Kingsbridge as the setting for his novel Rachel Ray (1863).

Eventually it was time for our celebratory slap-up meal, which on this occasion was at Twenty Seven. We went the whole hog, taking on the six-course tasting menu and accompanying wine flight. Our waitress, who was right-handed, had burned her right hand quite badly. We enjoyed the meal greatly; rather less so the cost.

We finished too late for the last bus back, but had booked South Hams Taxis to return us to Salcombe.

The following morning, we departed the cottage by the 10.00 deadline, catching our scheduled bus to Totnes and train back to London. Unfortunately, the seat bookings seemed to be missing in our coach on the GWR service into Paddington, and I couldn’t prevail upon the youthfully selfish skater boy in our seats to move elsewhere.

Hopefully he’s since fallen off and grazed his knees!

TD

July 2023

Leave a comment