We returned to complete the Coast Path in September 2025, basing ourselves in Swanage.

This nineteenth and final visit marked the end of a project begun in Minehead in October 2017, almost eight years earlier.

Pre-Covid, we would travel down for up to five days at a time but, since our ninth visit (Port Isaac to Holywell Bay), we have devoted a full week to each section.

During our previous expedition, in April 2025, we completed the section from Charmouth to Osmington Mills while staying in Weymouth. That left only 34 miles to complete, though some of this final stretch along the Jurassic Coast is rated ‘severe’ in the official guide.

Initial weather forecasts weren’t too optimistic, projecting frequent rain throughout the week. But, shortly before our departure, projections improved dramatically.

As it turned out, we enjoyed predominantly warm and sunny weather from Saturday to Tuesday, though Wednesday and Thursday were punctuated by heavy showers, sometimes thundery. Miraculously, we managed to stay mostly dry.

The journey down was straightforward and uneventful. We caught the 12:00 SWR departure from Woking to Wareham, transferring there on to a 40 Purbeck Breezer bus to Swanage Station.

We relied heavily on these Breezer bus services, operated by morebus, throughout the week. Buses were still operating to their summer timetables, though these were due to end imminently. All the services we caught ran to time and, as an added bonus, my Freedom Pass allowed me to travel free (but Tracy remains liable for £3 fares).

Though these bus services are very good, their routes often lie some distance from the coast, so it is necessary to plan walks carefully, or else resort to additional lengthy yomps inland.

This is particularly true of the section through the army ranges between Lulworth Cove and Kimmeridge Bay. Other than in high summer, this is mostly open only at weekends, and there is no bus out of Kimmeridge Bay. Indeed there are no easy ‘outs’ for several miles beyond the ranges.

Being in a celebratory mood, we opted for a taxi to ferry us from here back to Swanage and then out again next morning. The return journey cost a hefty £96.

On the subsequent day we had initially planned a shorter walk but, feeling strong and with the weather still holding, we decided to continue all the way into Swanage.

We both felt we needed a rest day afterwards though. And, had we completed on Tuesday, we would have had two rest days in succession: something of an anti-climax after front-loading the week so heavily.

So, accounting for all these factors, our weekly programme eventually turned out like this:

- Saturday: Osmington Mills to Lulworth Cove (6.1 miles)

- Sunday: Lulworth Cove to Kimmeridge Bay (7.1 miles)

- Monday: Kimmeridge Bay to Swanage (13.5 miles)

- Tuesday: Rest Day

- Wednesday: Swanage to South Haven Point (7.5 miles)

- Thursday: Rest Day

That’s a total of 34.2 miles.

Accommodation

We chose to stay from Friday to Friday, principally to accommodate the army ranges. Aside from Poole, just beyond the end of the Coast Path, Swanage is the only place of any size along this stretch, so that was the obvious choice as our base for the week.

Through Sykes Cottages we rented Claire Cottage at a cost of £754 for the week. A two bedroomed bungalow, it was perfectly located, a stone’s throw from Swanage Railway Station and the adjacent bus stops.

Originally part of a hotel, it is approached through an archway between the buildings located on the main road, directly opposite the Station. Despite its central location, it is fairly quiet, but the only outside space is a car park for the surrounding properties.

These surroundings do not quite live up to the description provided by Sykes:

‘Outside, you’ll find a charming space where you can enjoy the fresh Dorset air.

Whether you’re starting your day with a cup of coffee or ending it with a glass of wine, this outdoor area is sure to be a favourite spot during your stay at Claire Cottage.’

In almost all other respects, the Cottage met our needs, though – speaking of coffee – there was no means of making one. Regular readers will know that this is particularly important to me.

I had to buy a cafetiere from the nearby hardware store. Although the lid turned out to be broken when I opened the box, it still worked, so I have donated it for the benefit of future guests at Claire Cottage!

Swanage

The peninsula on which Swanage sits is known as the Isle of Purbeck. It is bounded to the north by the River Frome, which snakes into Poole Harbour from its source at Evershot, north-west of Dorchester, passing close beneath Wareham. Purbeck’s westernmost extremity is vaguer, some placing it west of Lulworth Cove.

Marble has been quarried here since Roman times and was used in the construction of most of the medieval cathedrals of southern England.

Swanage itself is a small town with almost 10,000 inhabitants. The first recorded reference is in the Anglo Saxon Chronicle, which refers to the loss of 120 Danish ships at ‘Swanwich’ in 877 AD.

A more utilitarian building material, limestone, was also quarried in large quantities. From the Seventeenth Century onwards, much of it was transported by ship from here.

Tourism became increasingly important during Victoria’s reign, the young Princess having visited herself in 1833.

Victorian Swanage developed under the patronage of John Mowlem (1788-1868). He was born in Swanage, son of a quarryman, but went on to found the Mowlem construction company. He and his nephew George Burt (1816-1894) developed much of the Town’s infrastructure, including Swanage Pier.

The first pier was built in 1860, specifically to ship stone from local quarries, but it soon fell into disuse. The wooden stumps are still visible in the harbour. The present Pier was completed in 1897, intended for use by the passenger steamers that plied between Swanage, Poole and Bournemouth.

Part was blown up in 1940, to forestall invasion. It was repaired after the War ended, but steamer traffic was already beginning to decline, the last service ending in 1966. It, too, began to deteriorate and was closed following storm damage in 1982.

Swanage Pier Trust took over in 1994 and there was a reopening ceremony in 1998. Since then, the Trust has overseen extensive renovation and redevelopment. Even in steady state, annual maintenance costs are some £200,000.

From the pier one can enjoy the curious Wellington Clock Tower, originally a memorial to the Duke, which was placed at the southern end of London Bridge in 1854. It should have contained a statue of Wellington, but there was insufficient money to commission one.

It soon proved an obstacle to London traffic, so George Burt had it transferred here by boat, presenting it to his friend Thomas Docwra. He incorporated it into his house in 1868. The four-faced clock had been left in London, so Docwra inserted windows were the clock faces should have been. There was once a spire, too, but that was replaced by a cupola in 1904.

His uncle Mowlem provided the Town with a reading room, known as the Mowlem Institute, built on the seafront in 1863. The Mowlem Theatre, built in 1967, now occupies the site.

Not far away is the stone monument Mowlem had built in 1862, to commemorate the Danish naval disaster of 877, complete with anachronistic cannonballs.

Burt built Swanage Town Hall in 1883, at a cost of £4,500. Its facade is also secondhand, having been rescued from London’s second Mercer’s Hall. That opened in 1676 but was extensively remodelled in the 1870s.

The railway reached Swanage in 1885, supporting its development as a seaside resort. The line was closed in 1972, but subsequently revived as a heritage railway.

Swanage features (as Knollsea) in Hardy’s ‘The Hand of Ethelberta’ (1876) and also in Forster’s ‘Howard’s End’ (1910). According to Manuel, Basil Fawlty was from Swanage, but there have been precious few real residents of note.

Perhaps the best known are TV cook Fanny Cradock (1909-1994), who was briefly resident in her childhood and the Canadian poet and artist P.K. Page (1916-2010), who was born in Swanage but emigrated to Canada in 1919.

Swanage is a fairly lively place, relatively well-to-do and conspicuously Conservative. The population is heavily biased towards older people and almost exclusively White.

When we arrived, the annual Swanage Folk Festival was getting under way. We visited the craft market, next to the main tent on Sandpit Field, from where we heard some rehearsals, but didn’t manage to make a performance.

Saturday: Osmington Mills to Lulworth Cove

It was a lengthy journey back to Osmington Mills. We caught the 09:30 30 Breezer service, which transported us to Osmington Garage via Corfe Castle, Wareham, Wool and Lulworth Cove.

Arriving at around 11:10, we walked swiftly down Mills Road, passing a small group of youngsters learning to ride.

Just as we reached the point where the coast path from Weymouth joins Mills Road, a sprightly elderly couple emerged, the gentleman sporting poles. They walked almost parallel with us, on the other side of the road, until we diverted into the public toilets for a comfort break before getting properly under way.

The Smugglers Inn looked as decorous as ever, though the clock outside was running an hour slow.

Formerly known as ‘The Crown’, Emmanuel Charles (or Carless) (1781-1852), was landlord here in the 1820s, while simultaneously ringleader of a notorious smuggling gang. Some 27 members of his extended family were convicted of smuggling offences, several of them either incarcerated in Dorchester Gaol or forced to serve in the Navy.

Passing to the left of the Inn, beside a terrace of 1840s coastguards cottages, we climbed swiftly to Bran Point, enjoying a clear view across to Portland and Weymouth.

Below, seabirds perched on the remnants of the Minx, a steam-powered coal barge that broke its moorings and was wrecked here in November 1927.

Descending gently to Ringstead, past a couple of small wartime pillboxes, we skirted the former village of West Ringstead. Only earthworks remain, mostly within a large field that slopes up towards Glebe Cottage. It incorporates parts of the Thirteenth Century village church.

Some have suggested that West Ringstead was destroyed by French pirates, or that the Black Death was responsible, but it seems more likely that people simply preferred other, more convenient locations.

We did not visit the shingle beach, turning inland to the Reef Café for coffee and Dorset Apple Cake. We had to supply a table number when ordering, so I hurried to the shadiest bench and shouted its number back to Tracy:

‘42 – The Meaning of Life!’

A man nearby said:

‘Only according to Terry Pratchett’

I thought to myself, ‘Surely it was Monty Python?’ But the correct answer is, of course, Douglas Adams.

‘The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy’ informs us that a massive supercomputer called Deep Thought took 7.5 million years to calculate that 42 is the answer to the ultimate question of life, the universe and everything.

We resumed along a track, passing The Creek Caravan Park, and the former RAF Ringstead, originally a Chain Home radar station, which became operational in March 1942.

Later, from 1963 to 1974, the United States Air Force maintained something called a Tropospheric Scatter Station here, using microwave radio frequencies, within the ACE High NATO Communications System.

There were formerly two parabolic aerials, each of them 150 feet high, but they were dismantled in 1975. There was considerable opposition to their construction here, not least from the Royal Navy, concerned about interference with their facilities on Portland.

The next headland is known as Burning Cliff. The name derives from an incident in 1826 when a landslide caused the spontaneous ignition of oil-shale. It continued to smoulder for several years.

In 1829 the site was visited by the Very Reverend William Buckland, Reader in Geology at Oxford University:

‘These pseudovolcanic combustions began in September 1826, and during a period of many months emitted considerable volumes of flame, probably originating in the heat produced by the decomposition of the iron pyrites with which this shale occasionally abounds…This pseudovolcano at Holworth commenced in the face of the cliff about twenty feet above the sea; its combustion was proceeding slowly when we saw it in September 1829, and it emitted no flame…The extent of the surface of the clay which has been burnt does not exceed fifty feet square. Within this space are many small fumeroles that exhale bituminous and sulphureous vapours, and some of which are lined with a thin sublimation of sulphur; much of the shale near the central parts has undergone perfect fusion, and is converted to a cellular slag. In the parts adjacent to this ignited portion of the cliff…the shale is simply baked and reduced to the condition of red tiles like on the shore near Portland Ferry.’

The route briefly joins a road here, passing beside a tiny wooden church, St Catherine-by-the-Sea, Holworth. Sources seem to disagree over whether it first opened in 1906 or in 1926.

The Reverend Robert Linklater (1839-1915), Anglo-Catholic vicar of Holy Trinity Church, Stroud Green in London, bought nearby Holworth House in 1887 as a holiday home.

He was granted permission to celebrate Holy Communion in its private chapel but, for some reason, it was decided that a separate church was necessary.

Linklater died in 1915 so, if the Church was built in 1926, the reason may have been the decision by his widow, Mary Catherine Linklater, to sell Holworth House.

The Church was extended and refurbished in 2010. Its bell once belonged to the submarine HMS Sleuth, launched in 1944 but broken up in 1958. As we passed, I was struck by the shape of the tiny bell tower silhouetted against the sky.

A service is still held here, on the fourth Sunday of every month. Meanwhile, Holworth House is presently up for sale – for a cool £2.5m.

The Coast Path sign beside the Church was nicely decorated.

We continued in the direction of White Nothe, where there is another terrace of former coastguards’ cottages – the biggest for the captain and six more for his men and their families.

There is also an unusual brick and concrete pillbox, topped out with a Royal Observer Corps observation post. It was probably constructed on the base of a Nineteenth Century lookout point.

Here we caught up with the sprightly couple we’d encountered earlier, braving the stiffening gale to chat for a while. It was their second time round the Coast Path though, this time, they were missing out the bits they didn’t like (such as Torquay). They had stayed the previous night in Weymouth, which they very much liked, and were having their bags transported from stop to stop.

There is a steep zig-zagging route from here down to the shore. Often referred to as Smugglers’ Path, it is sometimes suggested to be the very path that features in ‘Moonfleet’ (1898) by John Meade Falkner.

Our hero has to climb it with a broken leg:

‘It was a sight to stagger any man, and would have made me swoon perhaps, but that there was no time, for we were at the end of the under-cliff, and Elzevir set me down for a minute, before he buckled to his task. And ’twas a task that might cow the bravest, and when I looked upon the Zigzag, it seemed better to stay where we were and fall into the hands of the Posse than set foot on that awful way, and fall upon the rocks below. For the Zigzag started off as a fair enough chalk path, but in a few paces narrowed down till it was but a whiter thread against the grey-white cliff-face, and afterwards turned sharply back, crossing a hundred feet direct above our heads. And then I smelt an evil stench, and looking about, saw the blown-out carcass of a rotting sheep lie close at hand.’

Having waited for a party to pass in the opposite direction, we took possession of a stone bench overlooking the beautiful limestone cliffs ahead, the top of Durdle Door just visible.

We managed to eat our sandwiches while buffeted by the gale, even attempting a couple of panoramic photographs.

Lunch over, we were soon approaching an obelisk beside the path, one of two hereabouts. This is known as the southern beacon. Both are seven metres high and were erected in 1850, to serve as navigational aids for Royal Navy ships. Two walkers were resting on the plinth as we passed.

We continued above Bat’s Head, which contains Bat’s Hole, a kind of miniature Durdle Door in whiter limestone, with the sea stack known as Butter Rock adjacent.

From Swyre Head (one of two so-called on this stretch of the coast path), one descends steeply, into the dry valley of Scratchy Bottom, or Scratchy’s Bottom, one of Britain’s rudest place names.

The opening scene of the ‘Far From the Madding Crowd’ (1967) was filmed here. Allan Bates played Gabriel Oak, a whose sheep are driven over the cliff by his sheepdog.

We were now surrounded by day trippers, which made the stiff descent all the more tricky. I had my new poles as insurance but, having got this far round the Coast Path without them, I was hoping to manage without.

Shortly before Durdle Door we were passed by four topless men striding in the opposite direction. I invited Tracy to decide:

‘which of these gentlemen has the finest pecs,’

but she refused to make the call.

Durdle Door beach was also busy, but not so crowded as to detract from the beauty of the place. It is part of the 12,000 acre Lulworth Estate, which extends five miles along the coast and has been in the hands of the Weld family since 1641.

The present incumbent, James Weld, hasn’t always enjoyed a good relationship with Natural England. Between 2013 and 2015 there was a lengthy dispute over which had responsibility for maintaining the steps down to Durdle Door.

‘Durdle’ may be derived from the Old English word ‘thirl’, meaning to pierce, bore or drill; or else from the word ‘durch’, meaning ‘through’.

The rock arch was formed by the relatively faster erosion of a band of softer rock, while the adjacent band of limestone remained in place. Erosion will eventually cause the arch to collapse, resulting in another sea stack.

This was where Doctor Who regenerated in October 2023, Jodie Whittaker becoming David Tennant.

The surrounding cliffs are also prone to erosion, potentially causing rockfalls and landslides. In 2013 there was a major landslip at St Oswald’s Bay, removing some 20 metres of the coast path slightly beyond Durdle Door.

Continuing above Man’o’War Beach, St Oswald’s Bay and Dungy Beach, we descended the Hambury Tout Steps as quickly as we could, given that they were fairly crowded. Above, on the Tout itself, a group of tourists – were they Hindu, perhaps? – was communing closely with a herd of black cows.

Arriving at the bus stop, we had to decide whether to wait for the imminent X54 service, or wander for a while before catching a later bus. Given the crowds, and the fact that we’d be back next day, we decided to leave sooner rather than later. The journey back to Swanage took a little over an hour.

That evening we visited the Red Lion, which offers a range of ciders from the Purbeck Cider Company. Tracy (who likes cider and dislikes beer) enjoyed her Bushey Berry, while I (who like beer and dislike cider) reminisced with a pint of Wadworths 6X.

We headed outside, where Morris sides from the folk festival were drinking, and occasionally singing, much to the disgust of the table of twenty-somethings next to us, who worried aloud whether they would be similarly embarrassing in 50 years’ time!.

We had dinner later at The Salt Pig Too, part of a well-regarded local chain of eateries.

Sunday: Lulworth Cove to Kimmeridge Bay

This section is almost entirely within the Lulworth Ranges, which are closed on most weekdays, but not all, and open on most weekends, but not all. The access times for 2025 are here; those for 2026 are here.

When the Ranges are in use, red flags are flown around the perimeter of the ranges, while warning lights flash on Bindon Hill and at St Aldhelm’s Head.

They cover some 7,000 acres, all of it leased from the Lulworth Estate, and are officially part of the Armoured Fighting Vehicles Schools Regiment (AFVSR) Gunnery School, based at nearby Lulworth Camp.

Lulworth Camp, together with Bovington Camp, forms the Bovington Garrison. Originally established in 1899, they were adopted as training camps by the Heavy Branch of the Machine Gun Corps, then responsible for tank warfare, in 1916.

The Tank Corps split from the Machine Gun Corps in July 1917, while the Gunnery School at Lulworth was established in February 1918. Later, the Armoured Fighting Vehicles Schools were formed in 1937, with driving and maintenance training located at Bovington while gunnery training continued at Lulworth.

The original Bindon ranges, adjacent to Lulworth Camp, were extended in 1938 and again in 1943, when the Heath Tyneham Ranges were added to the East, the land having been requisitioned. Local inhabitants were removed in November/December 1943.

The land was not given up after the War, despite considerable local opposition but, in 1949, local farms were permitted to graze sheep and cattle.

Prior to 1975, public access within specified areas was permitted on just 40 days of the year. However, following publication of the 1974 Nugent Report, access was significantly extended.

Paths are marked by wooden posts with yellow bands and have been cleared of explosives. Walkers are asked not to stray beyond these markers, nor to pick up any metal objects, and to stay clear of buildings.

President Zelensky of Ukraine visited Lulworth Camp in February 2023, meeting Ukrainian soldiers who were being trained to operate Challenger 2 tanks.

Firing can be disturbing for local residents. A local newspaper report from 2011 says that people in Poole, some twelve miles away, reported rattling window frames and intense firing until almost midnight. An army spokesperson said it was a standard night firing session and blamed atmospheric conditions.

Just as we were leaving Swanage a Met Office yellow warning for thunderstorms appeared on my phone and, exactly on cue, a heavy rain cloud appeared.

We were clearly on the extreme edge of the area affected, but it began to rain as we climbed aboard the 09:30 30 Breezer departure back down to Lulworth Cove. There was a heavy downpour with accompanying thunder but, on arriving at Lulworth, we found it completely dry.

During the journey we enjoyed the company of a talkative man from Sussex who held forth on a vast range of subjects, including deer, the quality of bus interiors, cyclists, bus replacement services and the comparative attractions of Wool, Wareham and Kimmeridge Bay.

On the way down to Lulworth Cove, we passed the entrance to Lulworth Camp, marked by a pair of tanks bearing notices saying ‘Keep Off’ and ‘MoD Property: No Photography’.

How idiotic to park two tanks outside the Camp expecting them not to be snapped by every passing punter! But perhaps the signs on those tanks predate our ubiquitous smartphones.

We were under way shortly after 10:30, initially following the official coast path route past Stair Hole, where a small cove is protected from the sea by a low limestone cliff which has been punctured by the erosive power of the sea. This is how Lulworth Cove itself has formed.

Continuing down to the mouth of Lulworth Cove itself, I noticed this sign attached to the Coast Path marker, but was careful not to draw it to Tracy’s attention.

We stopped at the Boat Shed Café for refreshments and, for the first time, noticed the landslip on the Cove itself. This had happened on 18 February 2024, after the cliffs had been destabilised by heavy rain, so was not mentioned in our guidebooks.

Nor does it feature as an official route change on the South West Coast Path. The tide was apparently in, but we could see people clambering over the debris, though there were warning signs on the beach.

In something of a quandary, I asked the woman who made our coffees for her opinion. She said, given recent heavy rainfall, she didn’t personally think it was wise to climb over.

So we chose to follow her expert guidance, making our way through Lulworth Cove and following the route marked ‘coast path diversion’, which climbs Bindon Hill.

On reaching the top we struck a path that also clearly post-dated the information in my ‘Exmouth to Poole’ official guide, dating from 2016. This took us behind Lulworth Cove and then, by way of a lengthy staired descent, along the perimeter fence of the Ranges.

We passed a prominent red flag, inside the range perimeter, apparently forgotten by some unfortunate squaddie.

Continuing through scrubby undergrowth, we eventually emerged on the far side of the Cove, known as Pepler’s Point. A man was resting on the stone memorial to Sir George Lionel Pepler (1882-1959), a prominent town planner who lived in nearby Little Bindon.

We chatted with a couple who had ventured further round for a photo opportunity. They were waiting for another man, standing at the extreme end of the cliff, to get out of their shot.

The narrowness of the entrance to Lulworth Cove is most evident from this point. But it is said that, in 1785, a whale found its way into the Cove, just managing to escape before it could be killed. The original source for this tale is ‘The History and Antiquities of the County of Dorset, Volume 1’ (1774) by John Hutchins.

But, according to Hutchins, the incident happened almost thirty years earlier and, moreover, the whale might not have entered the Cove at all:

‘October 4, 1758, a whale came near the cove. The country people endeavoured to take him; but he broke from them, and was found dead a few days after, near the Isle of Wight, having been much wounded.’ (P163)

Returning the way we had come, we bypassed the ruined chapel and cottage at Little Bindon. A small monastery was established here in 1149 by twenty Cistercian monks from Forde Abbey. They stayed only 23 years, removing in 1172 to a new site on the river near Wool which they called Bindon Abbey.

Entering the Ranges, I noted that the risk of fire was ‘moderate’. It took me some time to realise that this referred to the burning variety rather than the shelling variety.

We descended to the viewing platform above the ‘fossil forest’ but decided against dropping all the way down. Three rather more intrepid walkers explored below, while we read the noticeboard above.

This informed us that, some 145 million years ago, a coastal forest of conifer trees began slowly to be covered by a neighbouring salt lagoon. When the trees died, their stumps and roots were preserved in sediment. This resulted in blocks of fossilised wood, but they have disappeared, most probably removed by Victorian collectors.

I was slightly underwhelmed.

Returning to the main path, we passed five ponies standing in a row, their faces towards the sea, ruminatively nibbling at the grass.

Shortly afterwards we came upon a taciturn man reading a book atop a pill-box. We saw him several times subsequently, but he kept his distance, remaining taciturn.

We arrived beside a small cove called Bacon Hole, overlooking Mupe Rocks and ‘Smugglers’ Cave’. Inside, one can still find a false wall with a small, square, wooden-framed doorway.

Mupe Bay, a crescent of sand and shingle backed by massive chalk cliffs, is open to bathers but somewhat inaccessible. We admired the view of several upcoming headlands before turning inland to make our second ascent of Bindon Hill.

This is particularly long and steep. Before starting the ascent, we spotted a bird of prey swooping close to the cliff edge. I paused half way up to get my breath, admiring the view of Mupe Bay and Mupe Rocks now far below. The breeze stiffened as we climbed.

The main rampart of the Bindon Hill Iron Age camp runs along this ridge for some two kilometres. The enclosed area is so large that a defensive purpose would seem unlikely.

We continued eastward along the ridge and, before too long, could see the towers of Lulworth Castle inland. It is a square three-storey building with a basement and a round four-storey tower at each corner.

Intended as a large hunting lodge, it was completed in 1609 for Thomas Howard, third Viscount of Bindon but, after his death in 1611, passed to Thomas Howard, Earl of Suffolk. King James I visited in 1615.

The Earl died in 1640 with debts of £26,000, leading to the sale of the Lulworth estates to Humphrey Weld. The Castle became Weld’s home after Bindon House, at Wool, was destroyed by fire in the Civil War. But it was seized by the Roundheads who used it as a garrison. Weld resumed occupancy after the War and King Charles II visited in 1665.

The interior was modernised by later Welds in the second half of the Eighteenth Century, and Thomas Weld (1750-1810) had King George III to stay in 1789.

Unfortunately though, the Castle’s interior was completely gutted by fire in 1929. It lost its roof and was left a ruin until restored by English Heritage, which completed the task in 1998. Since 2008 the grounds have been used annually by Camp Bestival.

We continued eastward above the bay of Arish Mell, the broad sweep of Worbarrow Bay behind. Descending sharply, we found a picnic bench some fifty metres from the beach and decided to stop for lunch.

‘Arish Mell’ is derived from the Old English words for a rounded hill (or a buttock) and a mill. The beach is closed to the public because of the risk of unexploded ordnance.

In 1820, William Baring, fourth son of Sir Francis Baring, one of the founders of Baring’s Bank, and Rev John Bain, the Rector of Winfrith, sadly drowned here.

The Royal Cornwall Gazette reported:

‘Having on the evening of the 9th inst. walked to the sea shore at Arish Mill, near the Castle, they were induced by the calmness of the sea to row out in a small boat belonging to Mr. Baring, which unfortunately upsetting, they were both drowned. This melancholy event becomes more afflictive from the circumstance of Mrs. Baring and the two Miss Bains accompanying them to the shore, and being eye-witnesses of the painful sight. While attempting to change places in the boat it upset within a hundred yards of the shore. The spring tides setting very strong off this rocky coast, probably prevented their being able to reach the shore.’

Since 1959 this has been where the pipeline carrying effluent from the Winfrith Atomic Energy Establishment, some six miles distant, enters the sea. The Winfrith reactors are long shut down, but the decommissioning process is not quite completed.

We could see two tank turrets poking out from the hillside here, presumably targets for those using the Ranges. Then a blue van marked ‘Landmarc: Supporting Safe, Sustainable Training Solutions for the Armed Forces’ drew up nearby. A man walked down to the beach and, after contemplating the water, returned to the van and drove back the way he had come.

Landmarc is a joint venture between MITIE and amentum which partners with the Defence Infrastructure Organisation (DIO), part of the MoD, to manage and operate the UK Defence Training Estate, including training ranges.

So it was probably Landmarc that had left that red flag flying near Lulworth Cove!

As we completed lunch, a man wearing a hood and leggings hurtled down the slope behind us, assisted by poles, stopped, swung his legs to and fro a few times beside the beach, then mounted the slope on the opposite side. The taciturn man passed by in his wake.

We resumed, passing Monastery Farm inland. Between 1794 and 1817, Thomas Weld helped establish a Trappist monastery, later called Lulworth Abbey, after it was raised to that status by Pope Pius VII in 1813. It was the first Roman Catholic monastery established in England since the Dissolution.

Six French monks, exiled from their home country, had arrived in London intent on crossing to Canada, but Weld invited them here instead. In 1817, some 59 monks returned to Melleray Abbey near Nantes.

Thomas Weld’s son, also called Thomas (1773-1837) renounced his wealth and entered the priesthood, becoming a bishop in 1826 and a cardinal in 1830.

We now faced the daunting task of climbing Rings Hill, which sits behind Worbarrow Bay. This is the location of Flower’s Barrow, another Iron Age Hill Fort, though coastal erosion has caused much of it to collapse into the sea.

Far below we could sea a passenger steamer making its way along the coast. This is Waverley, 693 tons, 240 feet long and with a 58-foot beam. The last Clyde paddle steamer built, she was launched in October 1946 and, since 1971, has been the world’s only operational sea-going paddle steamer.

Constructed originally for the London and North Eastern Railway (LNER), she worked commercially in Scotland until 1974, then sold to the Paddle Steamer Preservation Society for £1. The Society refitted her, restoring the original LNER livery on her funnels.

Since then she has been operated by the Waverley Steam Navigation Company, a charity formed by the Preservation Society. A further refurbishment in 2003 restored Waverley back to how she was in the 1940s, as well as installing two new boilers. These were again replaced in 2020.

Today, she was on her way from Swanage to Weymouth, along the Jurassic Coast.

During her 2025 sailing season, between May and October, she was scheduled to depart from over 70 ports and piers around the country, ultimately returning to Glasgow.

Finally reaching the summit of Rings Hill, we were soon overlooking the broad sweep of Worbarrow Bay. The western end is called Cow Corner. This is also the name given to that part of a cricket pitch rarely found by batsmen, so it might be an allusion to activity on the firing range.

Worbarrow Bay is open to the public when access is permitted through the ranges. Boats can anchor when the ranges are not in use. While firing is taking place, three safety boats patrol these waters. As far as I can establish, boats can’t legally be prevented from crossing the firing area, so the patrol boats must rely on their persuasiveness and on sailors’ goodwill.

There was a small yacht moored at the far end of Worbarrow Bay as we passed, and several people were strolling along the shore.

At the eastern end sits Worbarrow Tout, a high promontary now almost separated from the coastline.

At the turn of the Twentieth Century there was a tiny hamlet here, clustered round a coastguard station, but the station was demolished in 1912, hastening the hamlet’s decline. During the 1930s the area became popular with tourists but, by 1943, when the army requisitioned the land, only ten residents remained.

In 1910 a substantial house was built upon the cliff above the beach by Warwick Draper, a London barrister, who died in 1926. The Drapers were very well connected and hosted frequent visitors, including Mary Pickford in 1921.

When the army requisitioned the land, Warwick’s eldest son, Phillip Draper, used the family’s influential connections to try to get the house restored to his family. He was unsuccessful.

As we arrived beside the Bay, the weather was closing in rapidly, reducing visibility and bringing light drizzle. We decided not to visit Tyneham, down in the valley, continued along the top of Gad Cliff, looking down on the site as we passed by.

When the village of Tyneham was abandoned in 1943, some 225 residents were evicted from over 100 properties in the Village and surrounding area. The last person surviving who had lived there died, aged 100, in 2025.

St Mary’s Church, extensively restored but with Thirteenth and Fourteenth Century features, still sits in the Village, now serving as a museum and information centre. After requisition, the army agreed that, while they would not target the building for firing practice, its safety could not be guaranteed. Reports suggest that, by 1950, it had been hit at least twice.

Although deconsecrated, it is still owned by the Diocese of Salisbury. The MoD pays the Diocese rent of £1 per year. It was listed in 2020.

Tyneham School, was built in 1856 but had already closed by 1932. It has been restored to how it would have looked in its heyday. Some of the farm’s outbuildings have also been restored.

Tyneham House was built in the second half of the Sixteenth Century, but incorporated parts of an older manor house dating from the Fourteenth Century. The Bond family purchased the House and Estate in 1691, retaining it almost until requisition.

Following the death of William Bond in 1935, it was let, furnished, during the summer months until 1939. It was then requisitioned in 1941, to support the RAF radar station at nearby Brandy Bay, and compulsorily purchased in 1952.

Although the House seems to have avoided shell damage, it suffered from both theft and neglect, its roof collapsing in 1965. Following advice from the Ancient Monuments Board, it was decided that full restoration was impossible. So the army demolished part of the building, removing some features elsewhere.

The ruins remain inaccessible, but what remains of the south-west wing was given listed status in 2025.

In the gloom and drizzle we could see precious little of all this.

We must have passed the location of RAF Brandy Bay, described as ‘built on a ridge above Egliston Gwyle’. It was built in 1941 and staffed by about 40 men and WAAFs, one of a several along this stretch of coast.

The area was radar-heavy because, until May 1942, the Telecommunications Research establishment was based at nearby Worth Matravers. The monitoring station at Brandy Bay was part of a four-station network directed from Bulbarrow Hill, known as the southern GEE chain. It supported navigation by friendly aircraft and shipping.

Eventually we reached a large stone bench overlooking the descent down Tyneham Cap towards Kimmeridge Bay. Here we stopped for coffee and a snack, keenly awaiting the Emergency Alerts test, due at 15:00.

The rain had now stopped, though it remained rather gloomy.

We had already restarted when the alerts finally sounded on our phones, presumably delayed by the sketchy mobile reception.

Reaching the flatter land beneath Tyneham Cap, we continued around the headland past Hobarrow Bay and the sea ledge called Broad Bench, which is open to the public but was completely deserted when we passed by. The Kimmeridge Bay website highlights this area’s attractiveness to surfers.

Some twenty minutes later we finally reached the exit to the ranges and immediately found ourselves besides a noticeboard explaining the Kimmeridge Wellsite.

Extensive deposits of oil shale, a soft slate permeated with crude oil, are contained within the cliffs around Kimmeridge. It has been extracted since Neolithic times. By the late Iron Age, mining had become more systematic but, during this and the succeeding Roman period, the shale was used primarily to fashion jewellery and cups.

It began to be utilised as fuel early in the Seventeenth Century. This reached a peak by the mid-Nineteenth Century, when some 600 tonnes were exported annually, including’ allegedly, fulfilling a contract to light the streets of Paris in 1858.

Drilling for oil began here exactly a century later, in 1958, though attempts were made as early as 1935. Six wells have been drilled but only the second, dating from 1959, led to the discovery of significant oil and gas. It is thought to be the oldest continually producing site in the UK.

The oil is not obtained from the cliffs, but from rock hundreds of metres below sea level, requiring the use of a ‘nodding donkey’ beam pump. The yield peaked at 350 barrels per day, but is decreasing, and is presently nearer 65 barrels per day.

Otherwise, Kimmeridge Bay is essentially a large car park, a public toilet and a marine wildlife centre operated by the Dorset Wildlife Trust.

So we were delighted to discover that the car park contains a restaurant called Boat on the Bay, serving coffee and cakes and still open daily until 18:00.

Imagine our disgust at finding it already closed when we arrived at 15:45. This is hardly the way to endear oneself to tired walkers completing the section through the Ranges.

We had booked our taxi for 17:00, so now had over an hour to kill before it arrived. We ambled round to the marine wildlife centre, Tracy briefly venturing in. Then we sat for a while on a bench nearby, enjoying the view.

A group of people settled into a sheltered space behind a hut, from where they prepared to swim. Another man lay stretched full-length on the shore, as if trying to sleep there, a towel over his head.

Meanwhile Waverley returned the way she had come.

Fortunately, while taking a final walk on to the beach, we found our taxi had arrived in the car park some 20 minutes early, so we were back in Swanage by 17:15.

Given our failure to secure coffee and cake, we decided to eat out once more, at a small Mediterranean restaurant and bar, The Corner, where we both selected pizzas.

The large group behind, apparently waiting for a bus, debated ad nauseam whether Angela Rayner’s failure to pay the correct stamp duty was more or less heinous than Nigel Farage’s avoidance of stamp duty, by arranging for his partner to buy their property, though allegedly with his money.

Monday: Kimmeridge Bay to Swanage

Our original plan had been to continue as far as Winspit Quarry before heading from there inland to a bus stop, via Worth Matravers. But, given that the weather forecast was good, we decided that we would continue on to Swanage if we could.

Our taxi was waiting as we emerged at 09:25 and we were back at Kimmeridge Bay by 10:00.

Outside the toilets we encountered a little girl with her grandmother. We tried to interest her in the rainbow just appearing over the ranges behind her, but she was too sleepy to engage.

The road down to Kimmeridge Bay is part of the 1,800 acre Smedmore Estate, which charges sizeable tolls, ostensibly to cover the cost of maintenance. Walkers and cyclists go free but cars, other than taxis, must pay £6.00 a time.

Smedmore Manor was so named because it was owned by the Smedmore family, until they sold to one William Wyot in 1392. Some thirty years later it passed to the Clavell family through marriage, though they continued to live at Barneston Manor, near Church Knowle.

But Sir William Clavell (1568-1644) tried various means of exploiting Kimmeridge’s oil shale. He initially produced alum but, since this infringed the King’s monopoly, he was obliged to move on to glass and salt.

Sir William built Smedmore House nearby, circa 1620. But, having incurred debts of some £20,000, was forced to surrender much of his land, including Barneston. Since his own marriage was childless, his heir was a nephew, John Clavell (c.1601-1643).

He was not the ideal successor. William probably secured John’s pardon when he was sentenced to imprisonment for theft while at Brasenose College Oxford.

Leaving without a degree, John removed to London where he married beneath him and, resorting to highway robbery, was arrested in 1627 and sentenced to death. He was miraculously released, possibly as a result of royal pardon, and published a poem ‘A Recantation of an Ill Led Life’ (1628).

On removing to Ireland, John is reputed to have entered a second marriage with a 10 year-old heiress, but this doesn’t seem to have resolved his financial difficulties since, in 1638, he was entangled in a court case over money he owed his brother-in-law.

All this led Sir William to disinherit him, as well as his immediate family, including his various siblings. Instead, the Estate went to a different branch of the Clavell family. They improved the House in 1700 and again in 1760.

By 1817 it was in the hands of Rev John Richards Clavell (1759-1833). Initially he was thought to have died intestate, the estate passing to his married niece Louisa Mansel.

But then his housekeeper produced a will that apparently left the estate to Mr Barnes, a manager at Swalland Farm. The Mansel’s went to law and a jury ultimately found in their favour.

The Estate remains in the hands of the Mansel family, the present owner being Philip Mansel (b. 1951), a historian specialising in French and Ottoman history.

Our first task was to climb the steps leading up Hen Cliff to the Clavell Tower. It was built for the Rev John Richards Clavell in 1830-31. Contemporary reports suggest it might have been intended as an observatory and a marker for ships, though perhaps it was simply a folly.

After Clavell’s death, the Tower was used occasionally by the Mansel family, as a picnic venue and to entertain their guests. It is thought likely that the young Thomas Hardy courted Eliza Nicholl, daughter of the Kimmeridge coastguard, here in the 1860s. Hardy certainly drew the Tower, anyway.

His poem ‘Neutral Tones’ (1867) is about the end of their relationship:

‘We stood by a pond that winter day,

And the sun was white, as though chidden of God,

And a few leaves lay on the starving sod;

– They had fallen from an ash, and were gray.

Your eyes on me were as eyes that rove

Over tedious riddles of years ago;

And some words played between us to and fro

On which lost the more by our love.

The smile on your mouth was the deadest thing

Alive enough to have strength to die;

And a grin of bitterness swept thereby

Like an ominous bird a-wing….

Since then, keen lessons that love deceives,

And wrings with wrong, have shaped to me

Your face, and the God curst sun, and a tree,

And a pond edged with grayish leaves.’

By 1880, the Tower was being used by the Kimmeridge coastguards as a lookout station, retaining that function until the First World War. Though still used as a picnic site and even rented out as a holiday cottage, its condition began to deteriorate. By the late 1920s is was growing derelict.

In 1986, the Estate offered it to Dorset County Council, but they refused to take it on. In 1996 the Clavell Tower Trust was established and it first approached the Landmark Trust in 1998. Landmark also declined initially, given the Tower’s startling proximity to the much eroded cliff edge.

Eventually it was decided that the only solution was to relocate the Tower 25 metres further inland. The work was undertaken from 2006 to 2008, following an extensive fundraising programme.

The Tower remains 11 metres tall with four floors. It has been converted into holiday accommodation for two people. Four nights here presently costs from £664.

Since the cliffs continue to crumble at a rate of approximately 13 metres a century, the position of the Tower will become problematic again in roughly 200 years.

A sculpture placed here by Antony Gormley, one of five marking the 50th Anniversary of the Landmark Trust in 2015, was toppled by a storm into the sea just a few months later.

We made our way along Hen Cliff past a location known as Cuddle, where we spotted a hare or a jackrabbit sitting in the field beside us.

Beneath us were the Kimmeridge Ledges, limestone structures that extend into the sea from the bottom of the cliffs. Oil shale mining was undertaken here and, at Clavell’s Hard, there was a small quay where the shale was loaded on to barges. A tramway once ran back to Kimmeridge Bay.

Rounding Rope Lake Head, we were soon descending to a small wooded valley at Freshwater Steps, which stretches inland towards Encombe House and its 2,000 acre estate, presently owned by James Gaggero, Chairman of the Bland Group.

A fresh water stream drops into the sea over a small waterfall, not visible from the Coast Path. The steps, probably built in the mid-Nineteenth Century, have long since disappeared.

We stopped for coffee here, for I had packed a flask after Sunday’s debacle, overlooking the small bay of Egmont Bight.

Just as we got to our feet, we were passed by two men eating as they walked. Both had poles and knee protectors and what looked like QR codes on their backpacks.

We approached the long, steep climb up Houns-Tout, which rises to 150 metres above sea level. Following a serious landslip here in November 2023, a three-mile diversion had to be introduced via Kingston, inland, but a new route has now been provided, replacing what was once a steep, stepped descent.

I had drawn ahead of Tracy on the climb, coming level with the two guys who had passed us below. Thinking that they looked almost done in, I engaged them in conversation, hoping that would help all three of us up the climb.

They explained that they were fund-raising for Campaign Against Living Miserably (CALM), a suicide prevention charity, which started in 1997 as a helpline in Manchester, becoming a national charity in 2005.

The two of them – Matt Wall and Liam Kavanagh – had set themselves the challenge of carrying packs weighing 15kg over a distance of 5,475 miles, to represent the 15 people on average who commit suicide daily and the 5,475 who commit suicide each year in England and Wales.

On this occasion they were walking the full length of the Jurassic Coast Path, some 116 miles, from Exmouth to Poole. They had hoped to complete in three days, but were already well into their fourth.

They still had roughly 18 miles to complete, needing to reach South Haven Point (see below) before dark. Both were working the next day! They explained that they’d had very little sleep since they’d left Exmouth.

We had a longer chat with them at the top and on the diversion inland of Chapmans Pool and I promised to feature their Go Fund Me page prominently in this post.

Suicide prevention is a hugely important cause. The data is stark:

- Suicide is three times more common amongst men than women

- Amongst men, the suicide rate is highest for men aged 45-54

- In England, suicide rates are highest in the North East and North West

- In England, the suicide rate in the most deprived 10% of areas is almost double the rate in the least deprived 10% of areas

I’ve made a donation. I really hope you will consider doing so too.

We arrived above Chapmans Pool where, on 11 July 1866, the French barque Georgiana was wrecked. That led to the building of the lifeboat station at the eastern end of the bay, and the introduction of the lifeboat, George Scott.

But the decision proved foolhardy, because the boat could not easily reach vessels wrecked on the Kimmeridge ledges, while the station itself was frequently damaged by landslides. It closed in 1880 but the building remains.

Whereas the previous route descended to Chapman’s Pool before reascending, the Path now heads inland along the valley. Just before the turn, a house was enterprisingly advertising coffee and cakes. Though tempted to stop, we decided to press on.

We eventually emerged, through sheep, upon Emmett’s Hill, walking along the cliff top as twin paragliders swooped and soared nearby.

On the landward side, there is a wall, courtesy of the Dorset Dry Stone Walling Association. Embedded in the wall are five phrases on larger stones:

‘dark brought to light’

‘between turf and sky’

‘held by gravity’

‘hand built strata’

‘stones lean together’

The words were supplied by local poet and travel writer Paul Hyland, while the stones were carved at the Burngate Purbeck Stone Centre, Langton Matravers. They were installed between 2010 and 2012.

Also inserted in the wall is a memorial to Csgt Peter George Meacham MBE (1941-2020) which carries the insignia of the Special Boat Service Association. When Meacham was awarded his MBE in 2004, he was described as ‘Fitter and Turner, Ministry of Defence’. He must have led a more exciting life beforehand.

A little further on there is a memorial to Royal Marines killed between 1945 and 1990. It was placed here in 1990 by the Dorset Branch of the Royal Marines Association, not long after the September 1989 IRA bombing of the Royal Marines School of Music in Deal. Eleven marines were killed and 21 more wounded. No-one has been convicted of the atrocity.

There is also a secondary plaque commemorating those who have been killed since 1990.

Part of the memorial consists of stone benches. Walkers are invited to:

‘Rest awhile and reflect that we who are living can enjoy the beauty of the sea and countryside’.

We contemplated bringing forward our lunch but, despite the open invitation, it seemed somehow sacrilegious to the memory of those who had given their lives. So, after reflecting a little, as requested, we passed on.

The paragliders made yet another pass and then we were contemplating the two lines of steps, first descending then ascending, between us and St Aldhem’s Head.

The descent was fairly straightforward so, having built up a head of steam through the brief flat area, known as Pier Bottom, I began the ascent without a pause. Keeping my head down, I counted 112 steps and, expecting to be fairly near the top, looked up to discover that I was only half-way.

I walked the remaining steps in blocks of thirty or so, pausing for a few seconds after each block, and was extremely grateful to complete the climb. I believe someone has counted 217 steps all told.

Arriving at the top, I found Matt and Liam resting on a stone bench. Having commended my stair-climbing abilities, they were even more impressed by a man who was about to descend wearing a 20kg weighted pack. Who knows why.

They soon moved off, the last we saw of them, while Tracy and I took over their bench for our lunch, before strolling on to the end of the headland.

St Aldhelm’s Head is named after Aldhelm, Abbot of Malmesbury Abbey and ultimately Bishop of Sherbourne (c.639-709). However, the name is often corrupted to ‘St Alban’s Head’, recalling the martyr who died circa 300.

Here we found a row of four coastguards’ cottages dating from 1895 and, behind them, the squat square block of St Aldhelm’s Chapel.

This curious building is hard to explain. It may have been placed on the site of an earlier building with religious significance, a Saxon church perhaps. It was probably built in the Twelfth Century, but its features are not fully consistent with a religious purpose.

It is roughly eight metres square, the four corners pointing north, south, east and west. There is an arched doorway on the north-west face and a small lancet window on the south-east face. The outer wall is buttressed, so the building is clearly intended to withstand the elements to which it is exposed in this position.

Inside, a central stone pillar supports four arches and each of the four spaces created by these arches has its own arched ceiling. There is no evidence of an altar, while the cross outside, at the centre point of the roof, was added only in 1873. However, there are records showing that a chaplain was employed here in the Thirteenth Century.

It may have sustained this function into the Elizabethan era but, by 1625, it was described in a survey as a navigational aid, or seamark. The cross on the roof may have been preceded by a beacon. By the beginning of the Nineteenth Century it had fallen into disrepair and required extensive restoration before resuming duty as a chapel in 1874.

Some 400 metres away, there is the grave of a woman, dating from the late Thirteenth Century and the foundations of a building just two metres square, which might have been an anchorite’s cell.

Beyond the Chapel, there is a lookout station, now manned by the National Coastwatch Institution. This displays prominently a notice declaring that it does not contain public toilets. The station overlooks a dangerous tidal race and a ledge, some eight to 16 metres below the surface, that extends up to two-and-a-half miles south-west.

A little further round the headland one finds a striking memorial commemorating the radar research undertaken in and around Worth Matravers from 1940 to 1942. It was installed here in 2001. There is also a plaque recalling Dr W H Penley (1917-2017) who began in the radar team, eventually rising to become Head of the Scientific Civil Service.

Set on a Purbeck stone base, two interlocking, stylised radar dishes form a firebasket, combining both an ancient and a modern means of communicating the movements of prospective invaders.

This area has been quarried for centuries and there is still a functioning quarry here, established in 1934. In 2005 it supplied a new stone altar table for St Aldhelm’s Chapel, consecrated by the then Archbishop of Canterbury.

Rounding the headland, we continued north-east, finding some welcome bushes for a comfort break before arriving at Winspit, lying between the hills of West and East Man.

Quarrying was taking place here as early as 1719 and was firmly established by 1756. The earlier open quarries gave way to an extensive series of underground galleries, often supported by stone pillars carved out of the rock. Stone was removed from here by boat.

There is a memorial to Alastair Ian Campbell Johnstone, just 18 and recently at Harrow. He and a friend paddled a collapsible canoe out to sea to get a better view of a passing yacht race. The friend was saved but Alastair drowned.

Shortly afterwards, in 1940, the quarries were adopted as a military base, though details of their role are scant. Quarrying ended in 1953 and the site was opened to the public. The land was owned by Weston Farm, but in 2022 it was bought by the National Trust.

The galleries have become Dorset’s swarming site for bats, some of which hibernate here. Fifteen species have been identified including the rare greater horseshoe, serotine and Barbastelle bats. Some of the galleries have been closed to protect their habitat.

Several films and television series have used the quarries as a location, including Doctor Who and Blake’s 7. The location is also popular with climbers.

We rested awhile on a large upturned block and, reviewing our condition, agreed to press on rather than turning inland. We could see the Anvil Point Lighthouse ahead, and it didn’t seem too far distant. Looking backwards, the quarries resembled a large roundabout, surrounded by cliffs.

In January 1786, Halsewell, a 758 ton East Indiaman, was wrecked on the rocks between Winspit and Seacombe. Some of the soldiers and sailors aboard managed to scramble on to the ledges and into a cave, but had to scale the cliff to escape the rising tide.

The cook and the quartermaster made it to the top and sought assistance from the quarrymen, who tried to haul up men on ropes. Only 74 of the 240 people aboard survived. King George III visited the scene of the shipwreck which later featured in Dickens’ short story ‘The Long Voyage’ (1853):

‘They found that a very considerable number of the crew, seamen and soldiers, and some petty officers, were in the same situation as themselves, though many who had reached the rocks below, perished in attempting to ascend. They could yet discern some part of the ship, and in their dreary station solaced themselves with the hopes of its remaining entire until day-break; for, in the midst of their own distress, the sufferings of the females on board affected them with the most poignant anguish; and every sea that broke inspired them with terror for their safety.

But, alas, their apprehensions were too soon realised! Within a very few minutes of the time that Mr. Rogers gained the rock, an universal shriek, which long vibrated in their ears, in which the voice of female distress was lamentably distinguished, announced the dreadful catastrophe. In a few moments all was hushed, except the roaring of the winds and the dashing of the waves; the wreck was buried in the deep, and not an atom of it was ever afterwards seen.’

The path turned inland at Seacombe Cliff, heading part way along the valley known as Seacombe Bottom.

The pioneering female travel writer Celia Fiennes (1662-1741), who travelled side saddle, and visited every county in England, describes the location as it was over three hundred years ago:

‘At a place 4 mile off called Sea Cume the Rockes are so Craggy and ye Creekes of land so many yt ye sea is very turbulent – I pick’d shells and it being a spring tide I saw ye sea beat upon ye Rockes at least 20 yards with Such a ffoame or ffroth – and at another place the rockes had so large a Cavity and Hollow yt when ye Sea Vowed in, it runne almost round and Sounded like some hall or high arch.’

The quarry here was active from the 1770s and continued in operation until the early 1930s.

Next in the sequence is Dancing Ledge, where quarrying ended in 1914. Small ships could moor off the ledge, and stone from here was transported by that means to build Ramsgate Harbour.

There are two schools of thought about the name. It may be because the ledge is about the same size as a ballroom floor, or perhaps because it seems to dance when the waves wash over it.

The tidal swimming pool on the Ledge was occupied by four bathers as we passed by.

This was created at the urging of one Thomas Pellatt, Headmaster of Durnford School, who insisted that his charges should begin the day with a naked swim.

But even Pellatt acknowledged the dangers inherent in sea bathing here so, at the turn of the Twentieth Century, he had the quarrymen blast a hole in the ledge to serve as a pool.

Ian Fleming, who arrived at Durnford in 1914, was amongst those who underwent this rite of passage.

During the next section, we each had to battle our fears.

First, I saw a small slow worm slithering along the path just ahead. I was quick enough to make sure that Tracy didn’t see, and he slid into the undergrowth. But I had to explain why I had stopped. Her vault above and beyond the spot was prodigious.

A little while later, we faced a field of cows with calves. As we entered, a mother nervously called her offspring to her side. Then I came upon a small calf standing near its mother in a thicket, almost within touching distance. The speed of my progress to the gate was equally impressive.

Next we came upon two metal structures resembling aerials. These are, in fact, markers for use by shipping. There should be another pair further along, just beyond the lighthouse, but I must have missed those!

If a boat starts from the point where the first pair align, and finishes where the second pair do so, it has travelled exactly one nautical mile.

I haven’t discovered why the markers are equipped with ladders.

We were now homing in on Anvil Point Lighthouse, just 12 metres tall and built in 1881. It was automated in 1991. The keepers’ cottages are now holiday rentals, so it’s fortunate that the foghorn was discontinued in 1988.

Having passed beyond the Lighthouse, we arrived inside Durlston Country Park.

From 1863, George Burt began buying up land along the coast overlooking Durlston Bay, lying to the south of Swanage. He acquired 236 acres of rough pasture, downland and quarry workings, all with splendid sea views.

Burt wanted to develop ‘New Swanage’, a housing estate conceived as a suburban village, surrounded by parkland and pleasure grounds. He drew up a plan in conjunction with the Weymouth architect George Crickmay.

But, although Burt laid out roads and built villas to the north of this area, closer to the outskirts of Swanage, his grander scheme never materialised. However, he continued to encourage public access to the land itself, building access roads and walks, and planting extensively, including several exotic species from abroad.

Durlston Castle was built in 1887, again designed by Crickmay, to house café and restaurant facilities for visitors. For a short while Lloyds of London used the upper floor as a signal station and, from 1898 to 1900, Marconi borrowed it for experimental radio telegraphy.

Burt also commissioned a 40-ton globe, three metres in diameter, carved out of Portland stone and engraved with a map of the world. It consists of fifteen stone segments connected by granite dowels. The globe was erected in 1891 and listed in 1983.

As a third attraction, Burt opened to the public the three former Tilly Whim limestone quarries. They are named after the ‘whim’, a crane-like contraption used to load quarried stone on to the barges that shipped it away. These quarries had been active during the Eighteenth Century but became disused after 1812.

The caves were closed to the public in 1976, owing to the risk of rock falls. In November 2013 a woman drowned here when trapped in the caves by a rising tide. She and her brother had been engaging in ‘coasteering’, essentially exploration of a rocky coastline by climbing and swimming, without the aid of a boat or board.

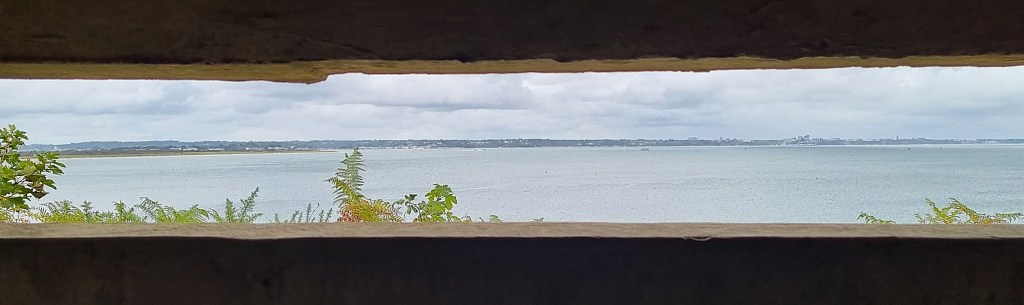

We sat for a while on the turf adjacent to the ledge and the seaward pointing caves, the cliffs of the Isle of Wight clearly visible beyond.

After Burt himself died in 1894, and despite willing to the contrary, development of the country park ground to a halt. The estate was put up for sale in 1919 by Edwin Burt and, a few years later, much of it was offered to Dorset Council. In 1936 it was eventually sold to a limited company established to run it.

During the Second World War another radar station was built here, known as RAF Tilly Whim. After that, the estate was run as a business venture by a local amusement arcade owner until 1973, when it was taken over by a partnership including Dorset County Council and Swanage Council.

The Castle was restored and reopened in 2011, now as a café and visitor centre. The Park now attracts over 250,000 visitors a year.

We made our way past these various attractions, following the newish Coast Path signage into a shady walkway surrounded by trees. Emerging on to the villa-lined roads built by Burt, we walked across the grass to the end of Peveril Point, then past the Wellington Tower and the Pier, where Waverley was now moored.

We stopped for a well-deserved ice cream at Scoopies.

Dinner was at home that evening but, during our first rest day, Tuesday, we compensated by enjoying breakfast at the Burnt Toast Café and afternoon tea at Love Cake Café!

Wednesday: Swanage to South Haven Point

The forecast looked ominous, with an 85-90% chance of thundery showers from mid-morning until mid-afternoon.

As we began, there were occasional sunny intervals but an otherwise cloudy sky. A larger blue patch materialised as we reached the end of the promenade. Although my guide suggests that one continues to the extreme end of the beach before climbing to Ballard Cliff via a narrow gully, this route is no longer signed.

So we followed the road route through the Ballard Estate. A first brief shower caught up with us on top of Ballard Cliff, but it had passed by the time we were approaching Old Harry Rocks at Handfast Point. The name most likely refers to the Devil himself.

These impressive cliffs and stacks were once connected to the Needles on the Isle of Wight. Erosion continues to form caves, which become arches. When an arch collapses it becomes a stack, and then a stump, before finally disappearing into the sea.

By the Fourteenth Century a castle had been built at Handfast Point, and there was still a castle here in the Eighteenth Century, but it has long since vanished into the sea.

When H. G. Wells died in 1946, his ashes were scattered in the sea beside the Rocks.

Turning with the headland, we followed the path to Studland Village. St Nicholas’s Church dates from the first half of the Twelfth Century, though with some degree of restoration. In 1880, large cracks appeared in the walls and were underpinned with concrete.

We were directed on to a path nearer the shore line, from where we could see the work ongoing at Middle Beach. The National Trust is removing thousands of tons of stone and concrete sea defences.

This is because, when waves hit the defences, they erode the sand below, meaning that the beach is now mostly submerged, so inaccessible. The sea defences have also become weakened and are at risk of collapse.

We stopped beside Fort Henry, at Redend Point, a bunker 90 feet long, its walls, floor and ceiling all three feet thick. This was built by Canadian Royal Engineers, the name referring to their base in Ontario.

There were heavy defences here from 1940, because this area was considered a likely invasion target. Pill boxes, dragon’s teeth and minefields were set in place.

But, from autumn 1943, it became a training area for amphibious assault, as preparations for D-Day began. Fort Henry was built to protect the VIPs watching these exercises.

On 4 April 1944, a major live fire beach assault training exercise was conducted here, under the codename Smash I. Six tanks were lost in high seas and several men died.

Two weeks later, on 18 April, Smash III was an even larger scale event, indeed the largest live fire exercise of the entire War. It was observed from Fort Henry by George VI, Churchill and Eisenhower, along with Montgomery and Mountbatten for good measure.

Continuing past beach huts, we arrived on Knoll Beach and stopped at the National Trust Café for a final coffee and cake. A phalanx of brightly coloured children’s slides emphasised the darkness of the clouds

We were soon surrounded by a bunch of brand new sixth formers out on a field trip. And, shortly after that, the rain began.

It was a heavy shower, so we waited for it to stop before taking to Knoll Beach and Shell Bay for the final push. There were very few people on the beach, apart from a few dog walkers. Light drizzle resumed as we interrupted a small group of waders investigating the seaweed.

We fell in with another couple who were also completing the Coast Path that day, discussing our most memorable experiences and the options for our next challenge.

As we entered the naturist zone, for this is the most popular naturist beach in the UK, we fully expected to find it deserted. One man strode up the beach into the dunes but, although naked, he was holding an umbrella. This seemed incongruous to me, and against the spirit of naturism.

We reached the end point, with its blue metal marker, at lunchtime. Sandbanks Hotel was close, across the water. I briefly recalled a long distant team awayday there, as the car ferry plied to and fro. Brownsea Castle was also visible.

It was a melancholy occasion, but we cracked open our champagne substitute and toasted ourselves in plastic flutes. A kind passer-by also photographed the occasion. Then it was time for our final picnic lunch before jumping aboard the first available 50 Purbeck Breezer back to Swanage.

For some strange reason, Tracy was keen to sit on top, exposed to the elements. I dutifully obliged.

To warm up a little, we dropped in to The Italian Bakery for coffee and cake.

Given that this was our last hurrah, Tracy had booked two slap-up dinners on successive evenings. Our first, this evening, was at Chilled Red. The food was excellent, though the décor was a little barren, while the curved windows are frosted, so there is little (other than diners) for the eye to rest on.

Rest Day

Our first rest day had been taken up entirely with exploring Swanage.

On the second, our final day, we began with a tasty breakfast at the Java Independent Coffee House before enjoying the full touristic experience of a trip on the railway to Corfe Castle. When I last had the opportunity, well over 20 years ago, the Fat Controller himself had been in charge.

The branch line from Wareham to Corfe Castle and Swanage opened in 1885, but passenger traffic began to decline, so it was closed in 1972, much of the track being removed.

Swanage Railway Society began restoring Swanage Station in 1976, laying a small section of track the following year. It took a further two decades for this to reach Corfe Castle and beyond.

I think we were pulled to Corfe Castle by ‘LSWR Adams T3 NO 563’, built originally in 1893, but restored in 2017 after it was donated to Swanage by the National Railway Museum.

Arriving at Corfe Castle Station, we admired our respective toilet facilities: Tracy investigate the mysteries of the ‘Ladies’ Room’ while I adjourned to the bulky urinals in the Gents.

Arriving at the Castle, we wandered the ruins.

Corfe Castle was founded in the Eleventh Century by William the Conqueror.

A century earlier, in 978, it is thought that King Edward the Martyr (born c.962), eldest son of King Edgar, was murdered here in an earlier Saxon building, potentially at the behest of his stepmother, Queen Aelfthryth.

A stone keep was added around 1105, early in the reign of Henry I (c.1068-1135). In 1139, his successor and nephew Stephen (c.1092-1154) besieged the Castle during his civil war with the Empress Matilda (c.1102-1167). The nearby earthworks known as The Rings were probably built by Stephen during the siege.

Further work was undertaken during the reign of John (1166-1216), who used Corfe extensively as both a prison and a royal residence. Henry III (1207-1272) also undertook significant improvements. There followed a period of comparative neglect until Edward III (1312-1377) made major repairs between 1356 and his death.

In 1496, Henry VII (1457-1509) had the Castle prepared as a residence for his mother Margaret, Countess of Richmond though, by 1499, she was living elsewhere.

In 1572, Elizabeth 1 (1533-1603) sold Corfe to Sir Christopher Hatton, her Lord Chancellor. It passed to his nephew, Sir William Hatton, and subsequently to Sir Edward Coke, who married William’s widow. Following Coke’s death it was purchased in 1635 by Sir John Bankes, Attorney General to King Charles I (1600-1649).

During the English Civil War, therefore, it was a Royalist stronghold and twice besieged by Parliamentary forces. In March 1646 Parliament ordered its demolition. The ruins were retained by the Bankes family as part of their estate until 1982, when they donated them to the National Trust.

Departing Corfe, we returned by bus to Swanage and, that evening, took our second celebratory meal at The Narrows, where I snaffled the last available helping of steak.

Next morning we packed and made our way back the way we had come. Walking home from the station we were, finally, caught by one of the thundery showers we had, thus far, miraculously managed to avoid.

It was a damp end to a glorious adventure.

Postscript

And so we conclude this eight-year project, begun after the loss of my wife, Kate.

Before her last illness, she bought me a guide to the Coast Path, writing inside ‘For when we go walking’, but we never got to walk the Coast Path together.

Instead, it has been my second partner, Tracy, who has accompanied me on this journey, our relationship maturing as we completed each stage. I am hugely grateful because, if it hadn’t been for her, I wouldn’t have made it all the way from Minehead to Poole.

I was already struggling with poor mental health when Dad died in September 2018, while we were at Ilfracombe. I recovered, somehow got through the Covid period and managed to avoid any relapse when Mum died in January 2022.

I have often thought of Kate, Dad or Mum while climbing a sheer cliff path or admiring a scintillating seaside vista.

But also, since Kate’s death, I have felt most happy and alive walking the Coast Path. During these very difficult years, these 630 miles have helped to keep me sane.

Which is why I was so struck by the efforts of Matt and Liam, who we met on this final journey. Their powerful commitment to suicide prevention was inspiring.

Do please give them a helping hand.

Thank you

TD

September 2025

Leave a comment