Unusually, the principal events in the life of Christopher Long Dracup are already available online.

This chronology is part of a website paying tribute to the 21st Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) – an infantry battalion formed in Kingston, Ontario – which fought in the First World War.

Though briefly a member of the 21st Battalion, Christopher was fortunate enough to avoid all combat, escaping in the nick of time, just before his comrades shipped to Flanders

A generation earlier, he had also escaped combat in the Boer War, buying a discharge on the eve of his Corps’ departure for South Africa.

But this very limited military experience forms only a small part of his fascinating life, which took him from England, where he was born, to Canada, then, during the First World War, to the United States.

He left behind his first wife and daughter in Liverpool, England and, within a few years, had become part of another family in Tacoma, Washington. Then, outliving his second wife and her parents, he returned to Canada, where he seems to have lived quietly until his death.

Christopher was an elusive man. Whenever he was required to supply factual details about himself, he found it almost impossible not to falsify some of them. And he would typically recycle these falsehoods, in a variety of official documents, over several years.

It is almost as if he had different versions of himself, swapping between them with facility as circumstances demanded, or where an opportunity arose.

Because he was so elusive, I have sometimes had to guess why he acted as he did – why he felt it necessary to adjust his own definition of himself.

This post is also relatively fact-packed and forensic, piecing together shreds of evidence from an array of different sources. I have tried hard to preserve the thread of the narrative, but it may be harder to follow here than in other posts in this series.

If you spot errors or omissions, or if you have further information, do please let me know.

His Dracup Antecedents

Christopher was descended from George Dracup (1775-1851), the youngest child of Nathaniel Dracup, the prominent early Methodist from whom most Dracups can trace their pedigree.

George was a shuttle maker, just as Nathaniel had been in his earlier days. George’s son, Samuel Dracup, also began as a shuttle maker, but was subsequently a pioneering manufacturer of powered Jacquard looms.

Samuel’s younger brother Edward (Neddy) (1796-1861) was Christopher’s great-grandfather. He too was described in the 1841 Census as a shuttle maker.

But the 1851 Census defines him as a ‘Master, worsted spinner, employing 8 men, 19 women and 20 children’.

By 1861, the Census refers to him as a ‘Linger maker’ (assuming I am deciphering the writing correctly). Presumably this was a specific component of the loom.

But his death notice, published in the Bradford Observer of 12 December 1861, described him as a shuttle maker once more. He died in Horton, Bradford, where he had been born.

His Grandfather – Robert Dracup (senior)

Christopher’s grandfather was Edward’s eldest son, Robert Dracup (1817-1899). In the various censuses, from 1841 onwards, he is invariably described as ‘mechanic’ (though sometimes ‘general mechanic’ or ‘machine mechanic’). By 1891 he was a ‘retired mechanic’.

At some point in the 1840s, he moved to Thornton, some six miles west of central Bradford. It was then a township within Bradford parish but, in 1865, it became a district in its own right, with its own Thornton Local Board. Then, in 1899, it was incorporated into the City of Bradford.

The Brontes had been born in Thornton while their father, Patrick, was at Thornton Chapel, prior to moving to Haworth.

According to Cudworth’s ‘Round About Bradford’ (1876), the population was 2,474 in 1801, but had reached 8,051 by 1861.

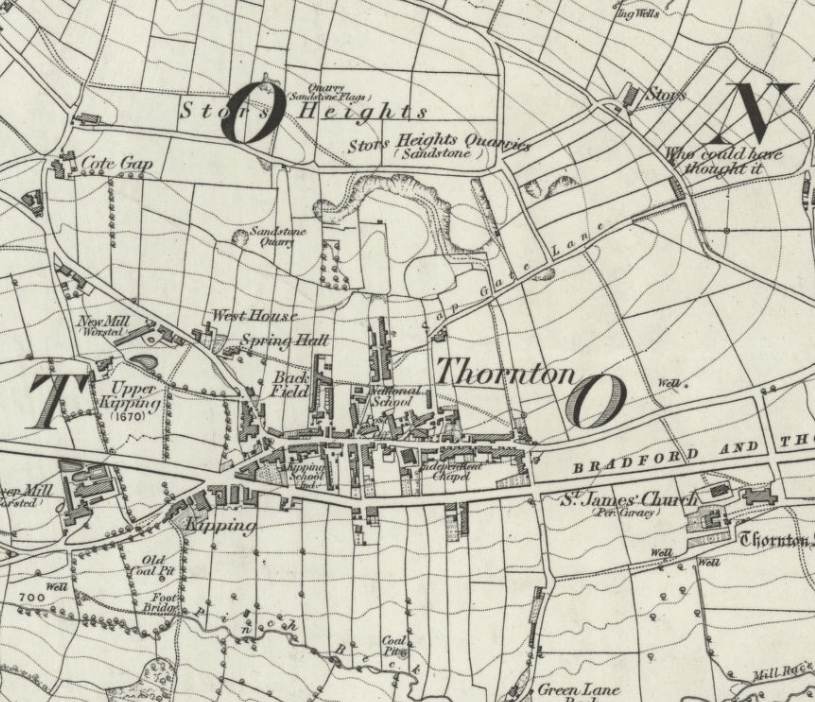

In 1851, Robert and his family resided in a property on Sapgate Lane (then known as Sap Gate Lane) and they remained there for both the 1861 and 1871 censuses.

Sapgate Lane began at the intersection with Market Street in the centre of Thornton and headed in a roughly north-easterly direction, passing to the south of the Storrs Heights quarries and joining Cliffe Lane (unnamed at this time) at a location bizarrely called ‘Who could have thought it?’

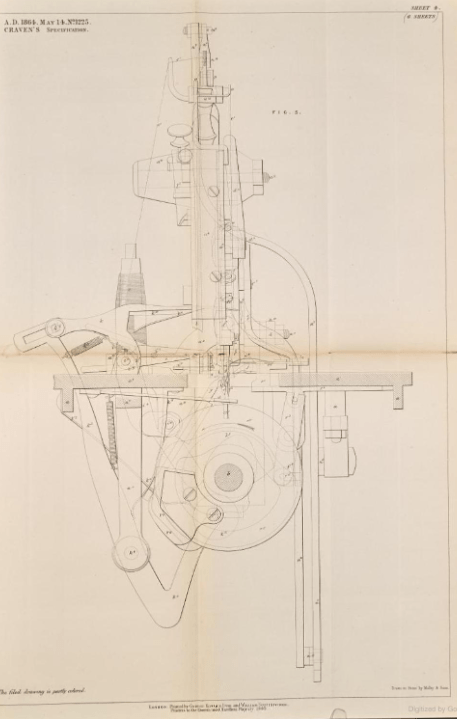

Robert was almost certainly the man who, according to contemporary newspaper reports, patented ‘improvements in the means or apparatus for combing wool and other fibres’ on 25th February 1862, with his partner, Thomas Watson, an overlooker.

According to their submission:

‘In apparatus for preparing and combing wool and other fibres, such fibres are operated by teeth in bars, or instruments, to which a progressive motion is given by the simultaneous movement of pairs of toothed wheels; but it sometimes happens that through such wheels being rigidly fixed to their shaft, and some obstruction arising, either in the fibre treated, or in the working of the mechanism, breakage takes place.

Now the object of this invention is to remedy this evil, by connecting such wheels to their shaft, so that whilst uniformity of action may be secured, a yielding may take place when any undue obstruction arises. For this purpose the bosses of such pairs of wheels are connected together by a bar or bars, or other suitable connecting means, and a strap or collar is applied to embrace the shaft, and the amount of adhesion is adjusted thereto by set screws or other suitable means capable of adjustment to the pressure ordinarily desired to be exerted.’

Seven years on, in 1869, the pair finally managed to pay stamp duty of £100 in respect of this patent: a substantial sum for two working men to find from their savings.

And, nine years later, in 1878, it seems that the Commissioners of Patents granted Robert and a new partner, one William Fearnley, provisional protection for six months in respect of another patent related to combing wool.

This was probably William Henry Fearnley (1847-1909), a wool-combing overlooker whose daughter, Lily Fearnley, later married Robert’s nephew Douglas Dracup (1877-1960).

By 1867, aged about 50, we know that Robert was the Head Mechanic at Messrs Joshua Craven and Son of Thornton. They were prosperous landowners, worsted spinners and manufacturers whose business was located in Swaine Street and at Prospect Mill, on Thornton Road.

Prospect Mill had been built by Joshua and Joseph Craven between 1848 and 1860, on a site Joshua had used since the early 1830s.

In those early days, he had been ‘master’ or employer of hand loom weavers – at one time upwards of 500 men and women. But he had afterwards turned to the manufacture of hand looms and subsequently, under Joseph’s influence, to power looms.

By 1851, Prospect Mill was employing 420 people operating 300 looms. And in 1854, the undertaking virtually doubled in size when spinning was introduced alongside weaving.

This is Joseph Craven (1825-1914), who later became the first Member of Parliament for the Shipley Division, sitting from 1885 until 1892. He retired from business in 1875, shortly after the death of his only son, also called Joshua.

We can place Robert with the Cravens because of a local newspaper report dated May 23rd 1867:

‘On Saturday, Mr Robert Dracup…while at work in the shop, had three of his fingers cut off by a circular saw. It is somewhat singular that, at the very time of the accident the unfortunate man was engaged in boxing off the machine which inflicted the injury upon him.

Mr Dracup is an old and faithful servant, being much respected not only by his employers, but by the inhabitants of Thornton generally, and much sympathy is expressed on his behalf. He was taken to the infirmary at Bradford.’

On 29 June, the Leeds Times reported that Joshua Craven and Sons had forwarded a £20 cheque to the Bradford Infirmary, in thanks for the treatment given to Robert:

‘A few weeks ago Dracup, who tends a saw mill, met with a severe accident, and lost three or four of the fingers of his left hand. He was brought to the Infirmary, amputation was found necessary, and was successfully performed. He recovered rapidly and returned home, and his masters have expressed his gratitude and their own by their thoughtful donation to the funds of the charity.’

It is interesting to reflect on Robert’s motivations in working for Joshua and Joseph Craven, who were direct competitors of his Uncle Samuel at Lane Close Mills in Great Horton (though Samuel himself had died in 1866). Perhaps he was offered better terms to move to Thornton.

Robert was married to Hannah Craven (1817-92), who may have been a distant relative of Joshua’s.

She bore him about a dozen children all told, including one (unnamed) who was reported by the Bradford Observer to have drowned in a deep garden well in April 1845. The inquest, held at the Four Ashes Inn, returned a verdict of Accidental Death.

In November 1872, the Thornton Local Board approved Robert’s plans to build three cottages at Storr Heights. Once constructed, he lived there for the remainder of his life, sometimes accommodating his relatives next door.

Today, these cottages are also located on Sapgate Lane, next to the Junction with Back Lane.

Four sons survived into adulthood:

- Henry (1840-1920), the eldest, was also a mechanic, though history does not record his employer. The 1891 Census describes him as both a mechanic and a farmer, but thereafter he was exclusively a farmer. He and his family lived at what became 7 Storr Heights. They had four children, including sons Douglas (see above) and Harold Henry.

- Nathaniel Harvey (1847-1912) has previously featured in ‘Dracups Emigrate to the United States: The Second Wave’ (June 2016). He and his wife Nancy, nee Bailey (1851-1932) emigrated in 1880 or thereabouts, settling in Jamestown, New York State, where Nathaniel worked as a woolsorter. They were responsible for establishing the Dracup family in Jamestown, where it survives to this day.

- George (1857-1935) was the youngest son. Also a woolsorter, he married Elizabeth Hannah, nee Shackleton, in 1880 and lived on Salt Street in Manningham. They had two sons, one of whom, John Vincent Dracup, died of wounds on 14 May 1917, during the Arras Offensive. George went on to marry twice more but had no further children; and

- Robert (1855-1936), Christopher’s father. Robert junior was employed as a worsted weaver at the time of the 1871 Census, when aged 16. He was one of nine children still living at home in the family house on Sapgate Lane. In August 1878, aged 23, he married Christiana, nee Long, in Hampsthwaite, Yorkshire.

His mother’s family

Christiana had been born in Hampsthwaite in 1855, the daughter of Thomas Long, an agricultural labourer, and his wife Abigail, nee Leedham.

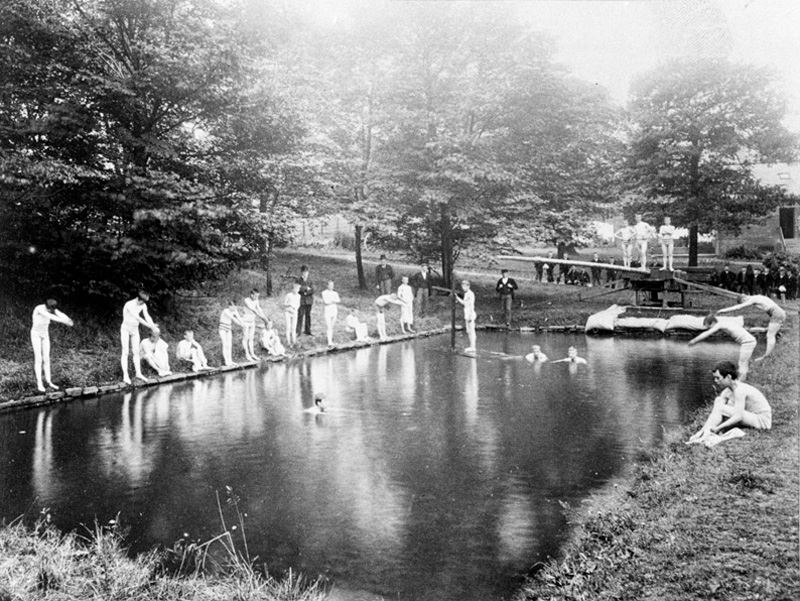

Hampsthwaite is a village some five miles north-west of Harrogate, on the south bank of the River Nidd. It is close to Ripley, the location of the earliest known Dracup in England, but roughly 25 miles north-east of Thornton.

Thomas Long and Abigail had married in Hampsthwaite in 1844. Thomas was a farmer, and the son of a farmer, while Abigail was a woodsman’s daughter.

However, by the time of the 1851 Census, Thomas was reduced to the status of an agricultural labourer – and he remained so until his death in 1878 at the age of 65.

There are numerous descriptions of his poaching activities in local newspapers, and he seems to have been imprisoned on several occasions.

The report of his death in the Knaresborough Post was as follows:

‘SUDDEN DEATH AT HAMPSTHWAITE: A man named Thomas Long, whose name will be familiar to many of our readers as that of a poacher, died very suddenly on Thursday morning, at his residence in Hampsthwaite. It appears that Long retired to bed in his usual health on the night of the 21st. His wife awoke about half-past-four, at which time deceased was apparently well. About half-past-six Mrs Long again woke, and found him moaning and breathing heavily. She awoke her son and he came, but the deceased breathed but twice afterwards. We understand that no inquest will be held, as it is supposed death resulted from heart disease, from which the deceased had for some years been been [sic] suffering.’

I can trace three further children, aside from Christiana:

- Elizabeth (b. about 1845) married Bramwell Rushforth, a carter on 1 April 1872, though we know he had married again by 1881. His several convictions include: 1865, at the age of only 13, stealing a horse (three months in prison and four years in Calder Farm reformatory); 1871, stealing a coat (12 months in prison); 1873, drunk and assault (fine or 21 days in prison); 1876, stealing two shovels (three months in prison); 1877, stealing a horse and harness (six months in prison); 1878, ‘rogue and vagabond’ (three months in prison); 1879, assault on a constable (three months in prison); 1880, fighting (fine or 10 days in prison); 1885, stealing a horse (12 months in prison);

- John (b. 1845) was an agricultural labourer. In 1872 he was summoned for refusing to leave a pub – and biting the landlord’s leg! There is mention of eight previous convictions for various offences. In 1873 he was fined for obstructing the station master and porter at Birstwith Station. In 1874 he was found guilty of assaulting one Elizabeth Milner, and again in 1877 for breaking her window. In 1882 he was charged with other men for attempting to poach fish in Tang Beck, and was fined 40 shillings or a month’s imprisonment. In 1887 he was caught poaching and broke his ankle while trying to escape. In 1892 he was charged with being in unlawful possession of game. In 1896, two of his children were charged with vagrancy and begging. There were several further charges for being drunk and disorderly.

- Thomas (b. about 1851) also an agricultural labourer. He was also in trouble several times for being drunk and disorderly. In 1884, he was one of three men who belatedly admitted unlawfully fishing in the River Nidd, thus exonerating three gamekeepers who had been falsely convicted of the crime. In 1892, he was found guilty with another man of night poaching and assaulting game watchers. They were imprisoned for three months with sureties. In 1896 he was charged with not sending his child to school and in 1897 for failing to contribute to the maintenance of his son, who attended a reformatory school. In 1904 he was charged with neglecting to maintain his four children, who had been supported for two years by the Knaresborough Union. Thomas was supposed to contribute 4 shillings a week but had done so only once. He was imprisoned for a month.

It is interesting to reflect on the potential impact of this genetic inheritance upon Christopher.

His parents

By 1871, aged 16, Christiana was employed as a scullery maid at the Royal Hotel, York Place in Harrogate, which is quite possibly where Robert met her. By the time of their marriage, he was employed as a mechanic, like his father.

A newspaper report gives Christiana’s date of death as 16 June 1879, at Hampsthwaite. This most likely places Christopher’s birth at 15 June 1879 (though he had other alleged birthdays – see below) and strongly suggests that Christiana died from the complications of childbirth.

By the time of the 1881 Census, Robert, now a 26 year-old widower, was living back in the parental home at Storr Heights, his employment described as ‘machine mechanic’, the same as his father’s. His son Christopher, aged only 1, was also residing there.

He must have been cared for by his grandmother and aunts for several years, since Robert did not remarry until 1886, when Christopher was seven years old.

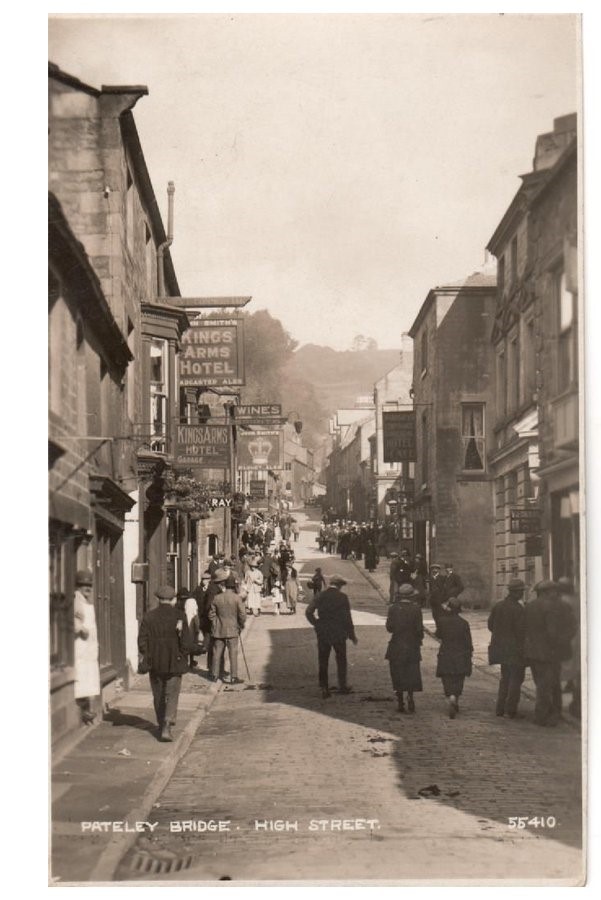

Robert’s second wife was Elizabeth, nee Summersgill (1864-1946). The wedding took place at Pateley Bridge in October 1886.

She had been born in Fountains Earth, some miles north-west of Harrogate and close to Pateley Bridge, to Joseph Summersgill, a farmer, and Dinah, nee Weatherhead.

Fountain’s Earth was a relatively short distance from Hampsthwaite, so it is highly likely that the Weatherheads and the Longs were known to each other.

Elizabeth’s mother had died in 1870 when she was only five, whereupon Joseph had married her mother’s younger sister, Hannah Weatherhead, who bore him several more children.

The 1881 Census records that Joseph had a farm of 37 acres. Unlike Thomas Long’s descent into agricultural labour, he remained self-employed.

It seems likely that, whereas Robert’s first set of in-laws were something of an embarrassment, Elizabeth’s family had comparatively higher social status, more fitting for the wife of a mechanic.

By 1891, Robert and his young family were living at 74 New Road, Thornton. (Confusingly, the electoral registers refer to ’74 Rawson Place’).

Robert, now aged 36, was described as a mechanic at a shawl manufacturer. This may have been the establishment of David and Joseph Craven which worked out of Thornton and Legram’s Mill in Great Horton.

Cudworth (1876) noted that Thornton:

‘…has long enjoyed a celebrity for the making of shawl cloths, technically known as Indianas or Cashmeres.

These shawl cloths are mostly dyed into blacks, and are finished with a wool, worsted or silk fringe. Fully one half of them in the finished state are exported to all parts of the world.

Although the cloth – a description of Coburg – was made here, the people of Paisley had acquired a celebrity for making it up into shawls by a fringing process, and consequently reaped the advantages therefrom.

Some years ago, however, Mr Joseph Craven, now deceased, devoted his energies towards both the dyeing and fringing processes with such success that those departments have been almost entirely withdrawn from Scotland and located here, from whence the goods are sent in the finished state.

By improvements which have been introduced, the fringing process formerly done by hand is now effected by machinery.

In 1864, Mr Phinehas Craven invented and patented a machine for this purpose of a somewhat elaborate character, but the machines now in general use were invented and patented by Mr Joseph Craven, of the firm of D&J Craven of Closehead, who are largely engaged in this particular trade. Fully 300 persons, mostly young people, are employed in this new branch.’

Elizabeth, now 26, had given birth to two more children – Joseph Reginald, aged two, and Marion, aged four months – while half-brother Christopher was 11 and at school. A fourth child, Norah Alma, was born in 1898 (and we know from the 1911 Census – which records child fatalities – that one further child had died).

The 1901 Census shows Robert still a mechanic at a shawl manufacturer and the family still at New Road, though Christopher had by this time departed. The other three children were aged 12, 10 and 6 respectively.

In 1911, the family were living at 3 Thornton Road, with Robert’s employment now described as ‘Mechanic in a worsted mill.’

By 1915, though, they had moved into 9, Storr Heights, his father’s old house, next door to brother Henry. Robert had owned a share of the freehold since his father’s death.

They remained in this property throughout the 1920s although, from 1926, the house number changed from 9 to 123 and the property’s name became ‘Storr Villas’.

His probate record shows that Robert remained there until his death, on 28 March 1936. He was buried on 1 April. Probate was awarded to Joseph Reginald, Marion and Norah Alma jointly. Christopher is not mentioned. Robert left almost £3,000.

At the time of the 1939 Register, Robert’s widow, Elizabeth, was living with her daughter Marion at 123 Sapgate Lane – the new address of 123 Storr Villas. She died in 1946.

His half-siblings

I should treat, briefly, of Christopher’s three siblings, whose lives did not match his for colour, being extremely respectable and relatively uneventful:

- Joseph Reginald remained at home in 1911, employed as a clerk in a worsted mill – most likely the same in which his father worked. He seems to have avoided wartime military service. On October 28th 1915, he married Doris Greaves Bransby at St John’s Church, Old Trafford, Manchester. Her father and mother had been joint managers of the Sale Hotel but, after her father’s death, her mother remarried, to a headteacher. By 1911, 17 year-old Doris was employed as a shorthand typist. By 1918, the married couple had settled in Ladybridge Road, Cheadle Hume. Here they remained, soon moving to a property in Woodfield Road. By the time of the 1939 Register, Joseph was a Departmental Manager at a Textile Manufacturer. There is some evidence that he also worked for a Craven: In 1942 J P Pearson Craven of J P Craven and Co, waterproof cloth manufacturers of Bradford and Manchester, left him £50 in his will. Joseph died on 7 October 1962, leaving some £10,000 to his widow, who died in 1981. I could find no record of any children.

- Marion was also at home in 1911, now aged 20, she was already employed as a Board School teacher. In 1909, she had matriculated from Carlton Street Girls’ Secondary School, Bradford. Her Teachers’ Registration Council record gives her date of registration as 1 August 1920. At that time, she was working at St James’ School, Thornton. Prior to this, from 1910 to 1911, she had been at Lilycroft Boys’ School, Bradford; and in 1911 at the Council School, Thornton, moving on to St James’ School that same year. From 1924, she occupied an unfurnished room at 9 Storr Villas and she was still living there in 1939. The 1939 register describes her as ‘Teacher (assistant, elementary)’. She seems to have remained unmarried. When she died in 1975, she was resident at 344 Thornton Road and left an estate worth over £22,000.

- Norah Alma was still at school in 1911. In 1923, she married Edgar Hardy (1884-1936) – a commercial traveller in blouses – and a son, Robert Geoffrey Hardy, was born in 1926. At the time of Edgar’s death, they were living at 19 Ashfield Road, Thornton. Edgar left his widow an estate worth just under £2,000. The 1939 Register locates her still at 19 Ashfield Road, and indicates that she was employed by a café as cashier and book-keeper. By 1957, she was living at Rivadale View, Ilkley, and when she died, on 1 November 1969, she was still resident there. She left an estate worth over £6,000. Her son Robert, born in 1926, married Dorothy Muriel, nee Townsend in 1951, and lived in Guiseley, dying in 1976.

Christopher in England

So Christopher’s most likely date of birth was 15 June 1879, the day before his mother’s death.

By 1881, he was a toddler residing with his widowed father in his grandparents’ house, the newly-built Storr Heights. And, by 1891, he was an 11 year-old schoolboy living on New Road, Thornton with his stepmother and two half-siblings, both considerably younger than he.

We know nothing more of his childhood, though it is fair to assume that he had little in common with his far younger half-siblings and was potentially out of place in the family.

One imagines that he might have identified more with his mother’s relatives, though they must have been looked down on by his father and stepmother, and with some justification.

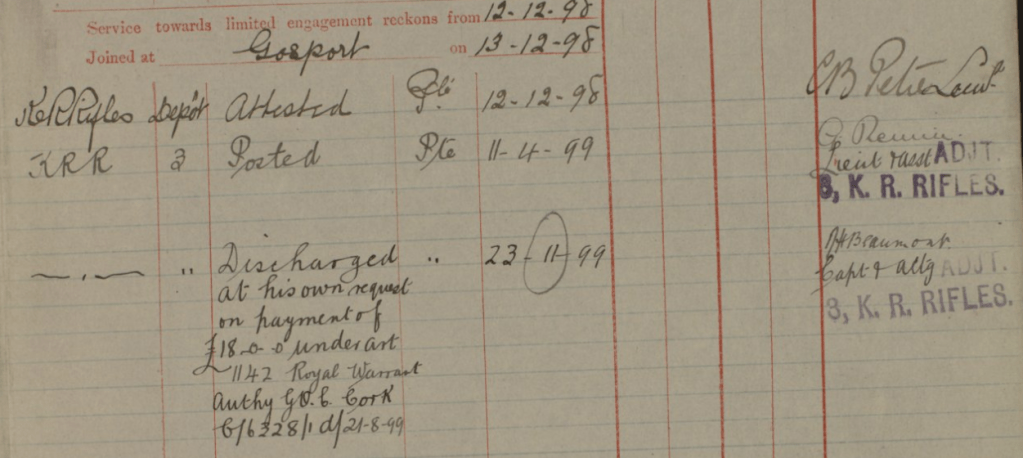

In December 1898, Christopher joined the King’s Royal Rifle Corps (KRRC) for his first stint in the military. He signed up for seven years of army service, followed by five years in the reserve.

His attestation paper gives his address as ‘Hamswaite [sic] near Bradford, Yorkshire’. This may perhaps suggest that he had been living with or near his mother’s family.

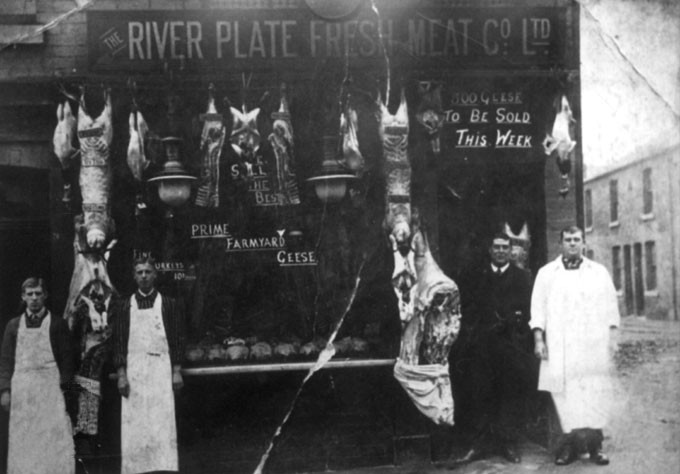

He states for the first time that he was previously employed as a butcher. There is no evidence to support this claim, (which he was often to repeat later), but it seems unlikely that a young man of 19 had achieved such status. More likely perhaps, he had been working as an assistant in a butcher’s shop.

He is described as five feet five-and-a-quarter inches tall, weighing 135 pounds, with a fresh complexion, hazel eyes and brown hair. There was a scar on his forehead, on the outside of his right eye.

As we shall see, his appearance was equally elusive, since the various descriptions we have of him are not fully consistent.

He gave his religion as ‘Independent’. This also changed later.

He was deemed fit for military service: notable given his later medical history.

During his service, he spent eight days in hospital from 7 March 1899 with a ‘mild chill’. He also reported to hospital in Kilkenny on 14 April 1899, shortly after his arrival there, but was not admitted. There is no reference to problems with his hearing or his ear.

His service record shows that, while he joined up in Bradford, he began his service in Gosport, Hampshire. The KRRC Deport was located here from 1894 to 1904, following a fire at their barracks in Winchester.

He was attached to the Depot until 11 April 1899, when he was posted to the 3rd Battalion of the KRRC, which was clearly based in Ireland at this point.

However, on 23 November 1899, he was ‘discharged at his own request on payment of £18-0-0 under Art 11 4 2 Royal Warrant Authy. GOC, Cork’. This is signed by Captain A H Beaumont.

The discharge is dated 23 August, three months earlier and Christopher had served a total of 255 days.

It was possible for soldiers in this era to purchase a discharge if they decided that they were not suited to the army. However, this cost £100 in the first three months of service, falling to £18 thereafter.

Even the smaller sum was typically beyond the means of private soldiers, who would often have to desert, or else injure themselves to obtain a medical discharge.

Quite where Christopher obtained this £18 is not recorded, but one assumes that his father paid. Christopher was still only 20 years old.

This timing was fortuitous, since the 3rd Battalion left England that very month for the Boer War, landing in Durban, South Africa on 30 November, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel R G Buchanan-Riddell.

It took part in all the battles leading up to the Relief of Ladysmith, including the Battle of Spion Kop where Buchanan-Riddell was killed. During the campaign, two further officers and 46 men were killed in action; another 11 officers and 195 men were wounded. A further 59 men died in hospital.

Christopher next appears two years later, in the 1901 Census. He was employed as a servant in the house of John James (1859-1929), a 41 year-old surgeon, who lived with his wife Jane, five children and a niece. There was one other (female) servant. The house was located a few miles inland of Aberystwyth, Wales, near Llandre.

There is no obvious connection between the James family and Christopher, so I cannot explain how he arrived with this particular family in this location. Maybe he had simply answered an advertisement.

There is a coincidence, however, in that the family’s youngest son, John Phylip James (1893-1972) also emigrated to Canada, in his case in 1912.

He was working as a labourer near Winnipeg when he also joined the Canadian Expeditionary Force, on April 11 1916. He served with Lord Strathona’s Horse (Royal Canadians).

On 1 April 1918 he received gunshot wounds to his left leg and hands, his right thumb shattered. He was invalided back to Canada where his right thumb was amputated.

After the War, the 1920 Canadian Census found him working as a labourer in Calgary, Alberta, but he later returned to England and settled in Buckinghamshire.

Christopher’s first marriage

In February 1907, in West Derby, Liverpool, Christopher married Mary Ellen Dawson – known as Nellie Dawson. They were both aged 27.

Nellie had been born in Kensington, London, in the summer of 1879, to Charles Alfred Dawson and Marie, nee Deeming. By the time of the 1881 Census, the family lived in West Derby, where Alfred was a hotel waiter.

Marie died when Nellie was 10 and Alfred remarried in 1891.

By the time of the 1901 Census, Nellie was working as a hotel waitress, quite possibly in the same establishment as her father. She continued to live at home, no doubt helping to look after her stepmother’s younger children.

The strange thing about the marriage is that Christopher entered into it under an alias: ‘Thomas Williams’.

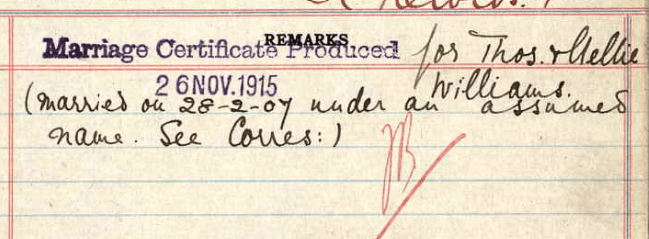

There are annotations on his WW1 service record – the form pertaining to separation allowance – stating that he had produced a marriage certificate on 26 November 1915, for ‘Thomas Williams’ and Nellie.

The annotations explain that the marriage had taken place on 28 February 1907, but under an assumed name. There is a reference to associated correspondence but, sadly, this is not included in the record.

We can only guess why Christopher felt he needed a second identity: presumably he wanted to cover his tracks, quite possibly fearing the consequences of his own wrongdoing.

He chose an extremely common alias – a cursory glance at the 1905-06 electoral registers for West Derby, Liverpool reveals more than 20 men called Thomas Williams.

A daughter, Doris Marie, was born on 31 May 1908, but I have been unable to find a birth record for either Doris Marie Dracup or Doris Marie Thomas.

As early as 1910, Christopher travelled to the United States. He was on board the SS Arabic, which sailed from Liverpool on 5 November, arriving in New York on 14 November.

He travelled under the name Christopher Long Dracup, aged 32, but claimed to be single, employed as a butcher, and said his last permanent residence had been in Bradford. He listed his father as his next-of-kin and gave his final destination as Jamestown, New York.

He was almost certainly planning to stay with his uncle Nathaniel Harvey Dracup who, by 1910, was living with his family at 78 Ellicott Street, Jamestown, employed as a woolsorter at a worsted mill. Nathaniel was to die only two years later.

One assumes that Christopher was lining up work in readiness for emigration to the United States.

He probably spent only three months in Jamestown. A labourer called Charles L Dracup returned from New York to Liverpool on the Lusitania on 14 February 1911; which would explain Christopher’s presence in the 1911 UK Census.

That found him reconciled to his proper surname, but still not to his Christian name. He called himself ‘Thomas Dracup’, stated his age as 32, his place of birth as Thornton, Bradford (not Hampsthwaite) and his employment as ‘farm labourer’.

He and Nellie had been married for five years (it was only four years) and, in addition to Doris, aged 2, they had had a second child, now dead.

The only other contemporary Dracup births in Liverpool I can identify belong to another Dracup family living in West Derby, the father being Clement Watson Dracup (1879-1914). They too lost one of their children.

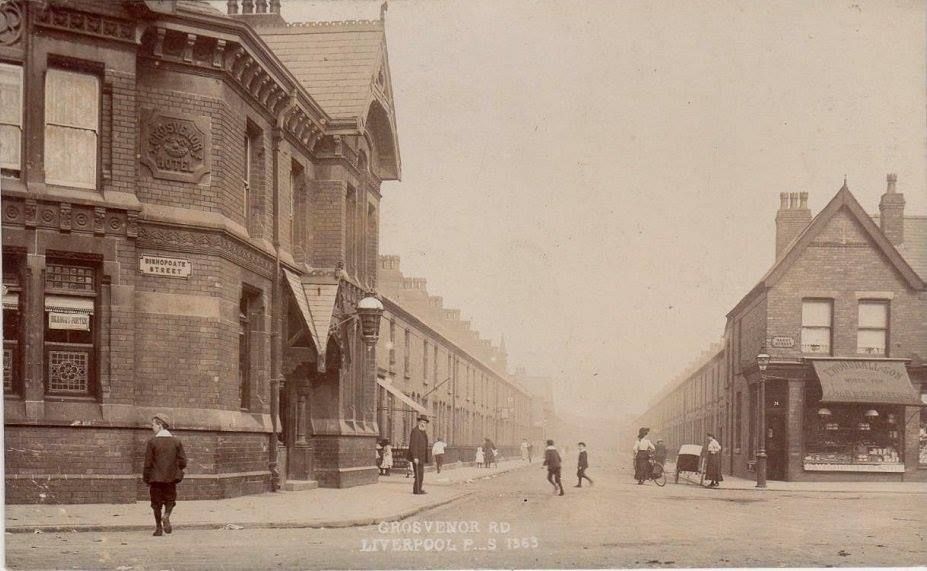

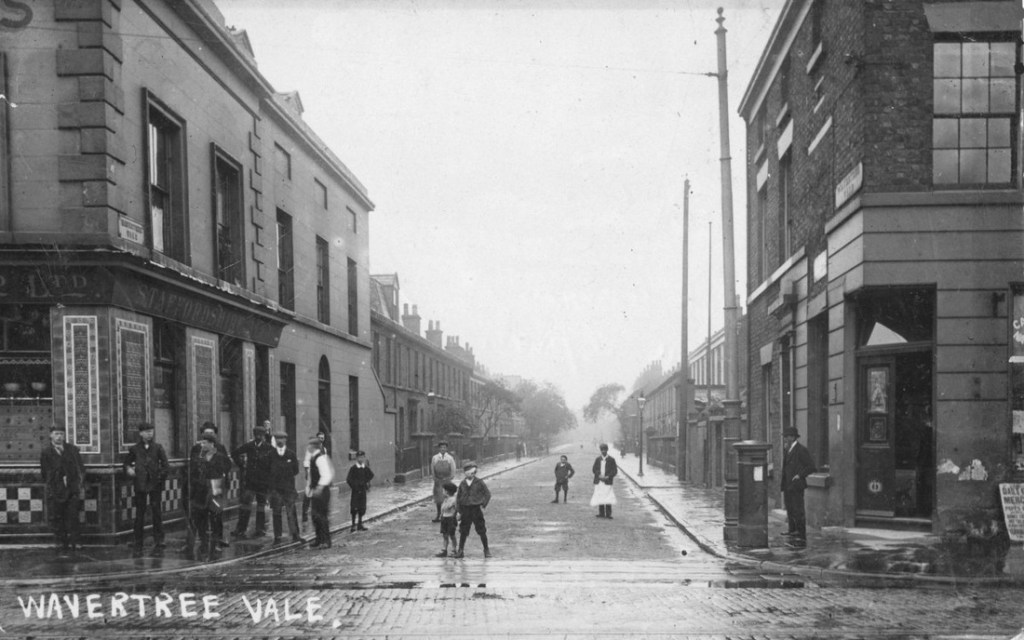

Thomas and Nellie’s address was 110, Wavertree Vale. At the time, Wavertree Vale ran between Grosvenor Road, to the south, and Picton Road to the north, between Ash Grove and Bishopsgate Street. The Liver Rope Works stretched between Wavertree Vale and Bishopsgate Street.

Today, Wavertree Vale is truncated, and its upper reaches are different roads, linked by narrow alleys.

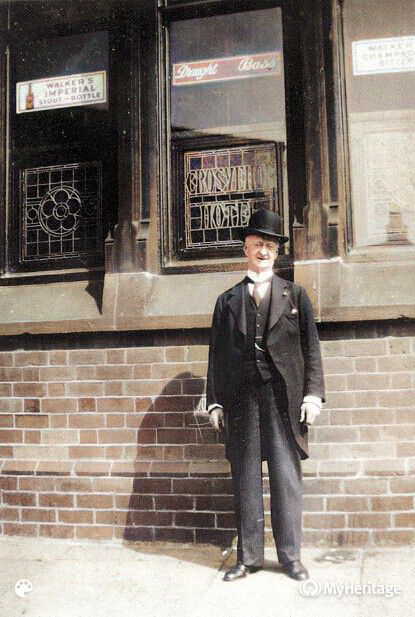

The Grosvenor Hotel was on the corner of Bishopsgate Street and Grosvenor Road, were it remains today. There are pictures placing Nellie’s father outside the Grosvenor, so that is most likely the place that both he and Nellie worked at the time.

Arrival in Canada

Perhaps his uncle’s death disrupted their plans to live in the USA because, on 12 April 1912, Christopher sailed from Liverpool on the SS Cymric, this time bound for Portland, Maine and then Halifax, Nova Scotia.

On the crossing to Maine, he acknowledged his marital status, giving Nellie as his next of kin, her address being Anfield Gardens, Anfield, Liverpool. His ultimate destination was Ontario.

But, on arrival at Halifax, he called himself Chris and claimed to be single again. He confirmed his intention to reside in Canada but said he was heading to Halifax, rather than Ontario. He agreed he was literate but, unaccountably, claimed to be from Bulgaria and to speak Bulgarian! He said he was employed as a farm labourer.

Then, on 19 July 1912, Mrs Nellie Dracup, aged 31, accompanied by ‘Maria’ aged 8, arrived in Quebec aboard the SS Empress Of Britain. They intended to settle in Stirling, Ontario and there is a supplementary note ‘to husband farmer 9 months’.

Had Christopher led her to expect that he farmed his own land, rather than working as a labourer for others? The distinction between his first father-in-law and his stepmother’s father springs once more to mind.

The 1913 City Directory for Belleville, Ontario places them in that town, their address being ‘311 Pinnacle’. We know from Christopher’s Great War service record that, by 1914, the family was resident at 13 Baldwin Street.

Christopher was working as a labourer.

A Short War

Then the First World War began.

Christopher was apparently added to the complement of the 21st Battalion as a Pioneer Private in November 1914, some four months prior to his formal attestation.

Authority to form the 21st Infantry Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force had been granted in October 1914. The Commanding Officer of the Princess of Wales’ Own Regiment (PWOR), Lt Col William St Pierre Hughes, was appointed to lead the new Battalion. The men were drawn from the various districts of Eastern Ontario.

The Battalion formed part of the 4th Infantry Brigade of the Second Canadian Divison. It was initially divided into eight companies, lettered A to H. The Headquarters were located at the Armouries in Kingston, Ontario; one half of the Battalion was based at the Royal Canadian Horse Artillery stables in Artillery Park; the other at a large mill building on Gore Street.

Christopher was taken on the strength of the Battalion on 11 November 1914, given the number 0171 and assigned to B Company. His pay record shows he was paid from 11 November until January 14 1915, but then discharged until formal attestation had taken place on 22 March.

His attestation paper states, falsely, that he had been born at his present address in Belleville, Canada, in May 1883, making him not quite 31, rather than his true age of almost 36. Presumably, he believed that being more youthful and Canadian-born would increase the likelihood of acceptance.

He admitted to his wife and child, aged 6, and correctly stated that he was working as a labourer. He denied ever having served in any military force, conveniently forgetting his time with the King’s Royal Rifle Corps some 15 years earlier.

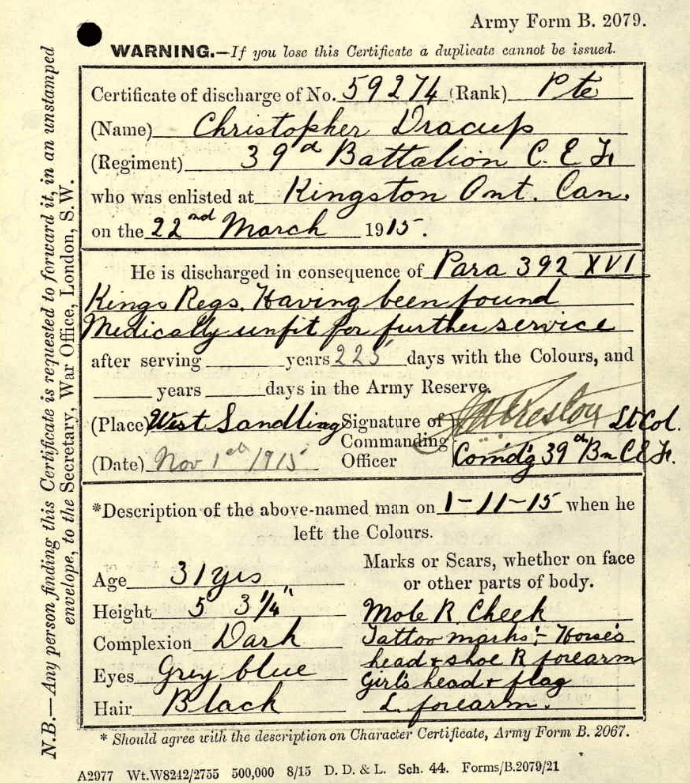

Since 1898, he had apparently shrunk two inches, to five feet three and-a-quarter inches tall; his complexion was now dark rather than fresh; his eyes grey-blue rather than hazel; his hair black rather than brown. And he was now Church of England rather than Independent.

The scar by his eye had disappeared, but he now had a mole on his right cheek and a new scar below his knee. He sported tattoos on each forearm: a horse’s head and shoe on the right forearm; a girl’s head and flags on the left.

He was declared fit for overseas service.

After initial training in Ontario over the winter and spring of 1915, the Battalion, Christopher amongst them, departed Kingston by train on 5 May.

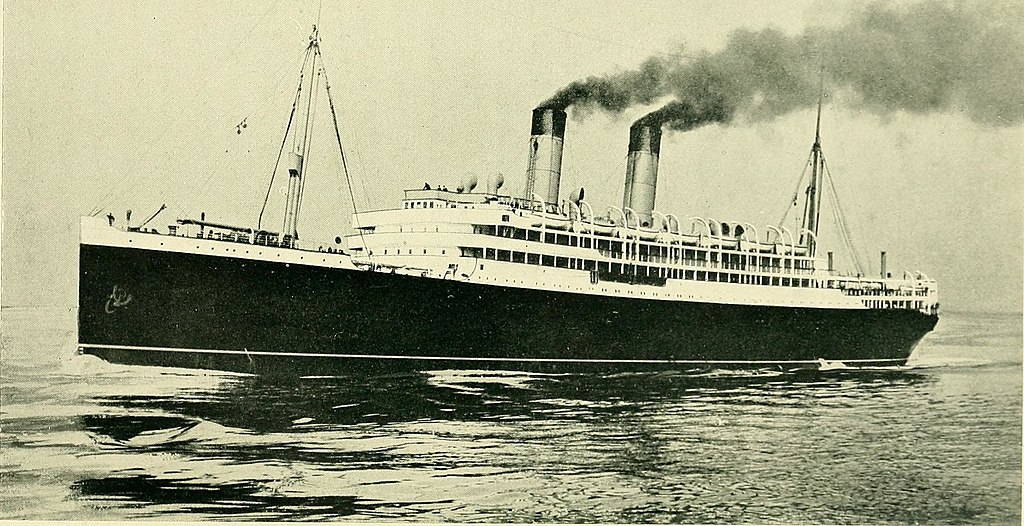

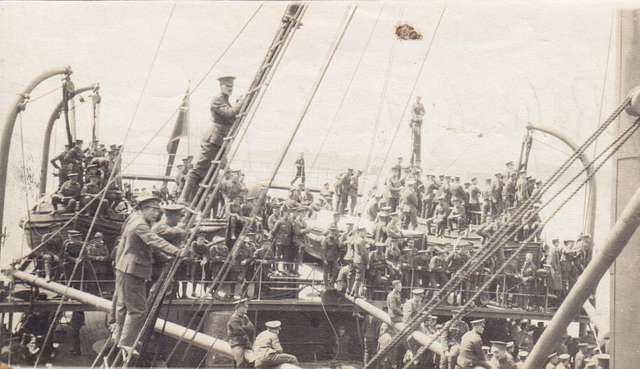

They shipped to England on the RMS Metagama, which departed Montreal on 6 May, arriving in Devonport, England early in the morning of 15 May.

Christopher was an Englishman, masquerading as a Canadian, returning to his true home country.

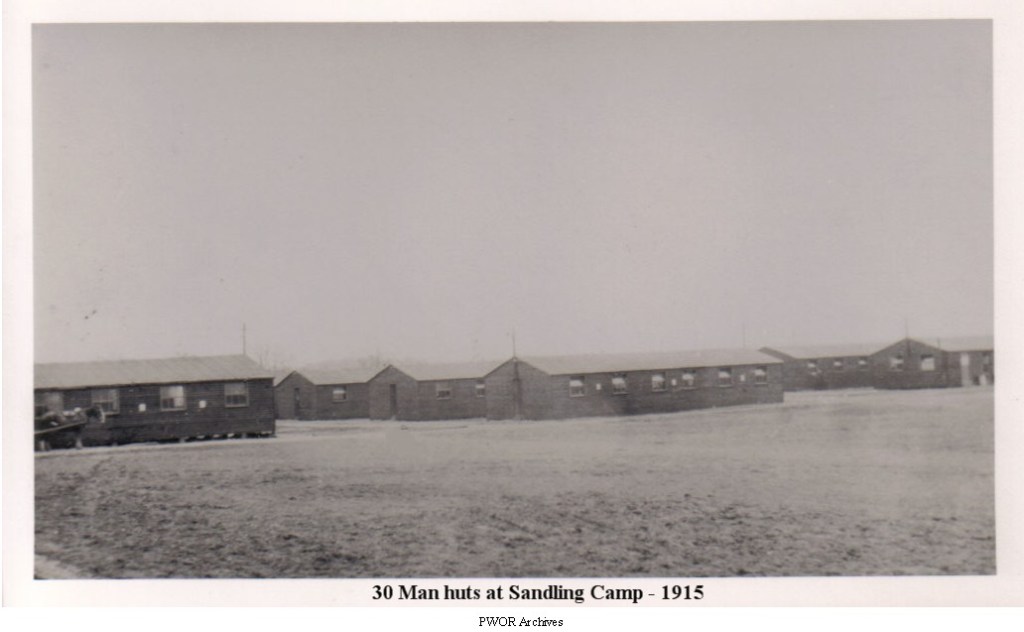

The Battalion took the train to Westenhanger, Kent, from where they marched to their quarters, at West Sandling Camp. This was located near the village of Sandling, some miles inland of Hythe, so convenient for subsequent transfer across the Channel to France.

Contemporary accounts of West Sandling mention the wooden cabins, the poor food and the strictness of British military discipline.

One soldier wrote home to relatives in July 1915:

‘The air and weather are certainly fine here. I like the country but do not care much for the towns, the streets seem so narrow and crowded. I don’t think I could live in one very long. The camp is nothing like the exhibition, we are living in long wooden huts, thirty men in each. Each man has two boards to go across two blocks, with straw mattresses and blankets and they are folded up and stood against the wall in the day. They are pretty comfortable. Of course the work is much harder here, and we are settling down to hard training and little discomforts.’

Another man wrote:

‘Everything is dear here, it’s because it’s so near the training divisions. They think we Canadians are millionaires, I guess. We went to a restaurant and got ham and eggs with no potatoes or coffee and with two slices of bread each- that cost one and six each. That’s thirty six cents in Canadian money. They talk about twenty five cents as going as far in England as a dollar in Canada, but I fail to see it. I get my washing done every week. Lots of women come to the camps for washing. They get lots to do and do it cheap. I get my fatigue pants, fatigue shirt, one undershirt, one towel and two handkerchiefs washed for one shilling, 24 cents. That’s not bad at all.’

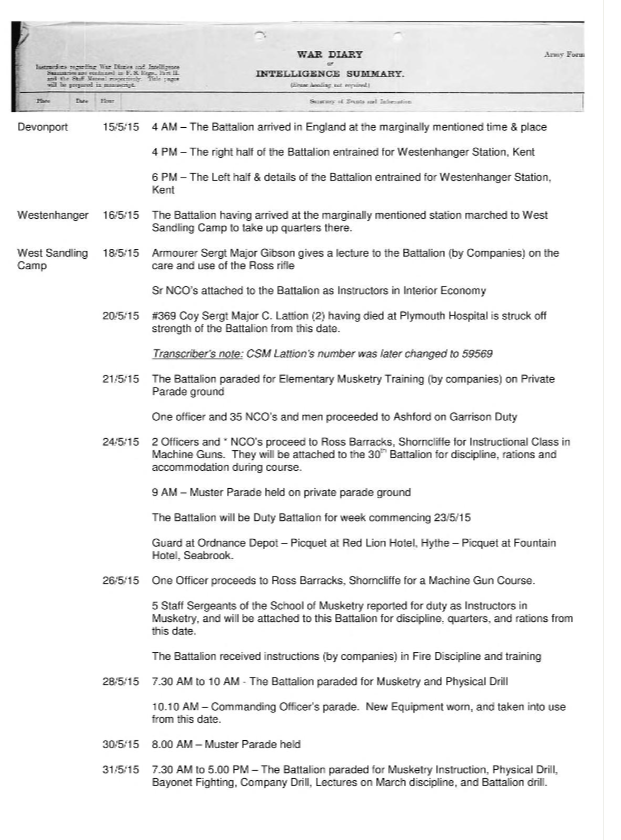

This page from the Battalion’s War Diary show how it utilised the remainder of May 1915, preparing for imminent combat.

Christopher’s service record states that he was initially admitted to the Canadian Military Hospital on 8 September, but discharged the same day. The Hospital was located at Beachborough Park, two miles from the Camp, and was staffed entirely by Canadians.

On 9 September, though, Christopher was transferred from the Pioneers to the Depot Company.

Just five days later, on 14 September, the bulk of his Battalion travelled to Folkestone and then on by sea to France. By 19 September, his former comrades were stationed at the Front, in trenches near Dranouter, Flanders.

Meanwhile, Christopher’s service record reveals that on 25 September, he was transferred from the Depot Company to the 39th Battalion, kept in reserve at Sandling to supply reinforcements as and when needed.

But medical investigations were ongoing. There is a medical report on his file, completed on 20 October. It states his correct age, rather than the age he pretended when joining up – ie 36. However, it preserves the illusion that, prior to enlistment, Christopher had worked as a butcher.

His disability is defined as ‘Chronic Supperative [sic] Otitis Media – Deafness’

The report explains that this originated in childhood:

‘Following measles in childhood has had a chronic discharge from the left ear intermittent in character. Has been steady discharge past six months, past three months has been deaf partially. Has been attending ear clinic Moore B. Hospital last 3 weeks.’

It adds for good measure:

‘General examination – shows poor general condition. Several missing teeth. Left ear shows a putrid permanent discharge with narrowing of the canal.’

And:

‘Advised hospital admission MBH, but this was refused’.

It recommends that Christopher is discharged as permanently unfit for service.

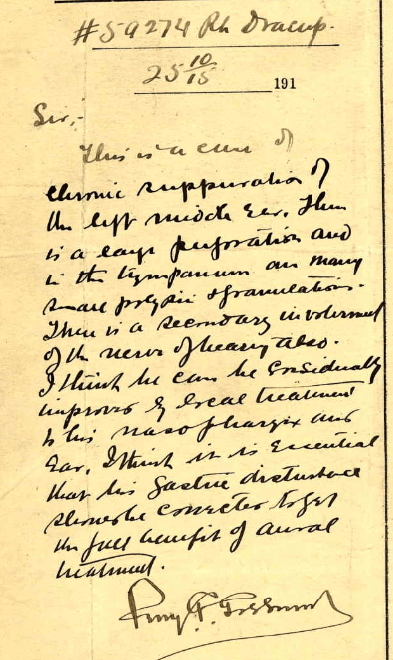

There is also a memorandum dated 25 October, addressed (in execrable handwriting) by a Major to the Medical Officer of the 21st Battalion:

‘Sir – This is a case of chronic suppuration of the left middle ear. There is a large perforation and in the tympanum are many small [unreadable] of granulation. There is a secondary involvement of the nerve of hearing also. I think he can be considerably improved by [great?] treatment to his nasopharynx and ear. I think it is essential that his [gastric?] disturbance shows the character to get full aural treatment.’

Make of that what you will!

Atlantic Crossings

On 1 November 1915, Christopher was confirmed medically unfit for further service. He was struck off the strength of the 39th Battalion and shipped back to Canada on the Metagama two weeks later, 14 November 1915.

He disembarked in Quebec City where he finally left the Discharge Depot, once more a civilian, on either 20 November or 28 December 1915 (the paperwork disagrees, but the later date is more likely).

But, if Christopher returned home to Belleville, he would have found his former home deserted, for Nellie and her daughter had already departed for England. We do not know whether he had received a letter from Nellie, advising him of her intention to follow him there.

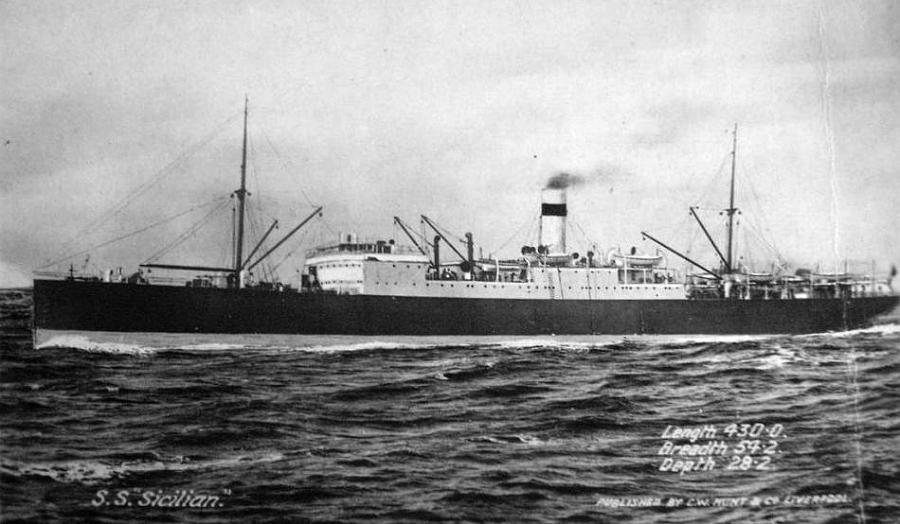

They were on board an Allen line ship, SS Sicilian, which must have departed Montreal in late September, since it arrived in Plymouth, Devon, on 9 October 1915. Nellie was recorded as a 36 year-old housewife, accompanied by 7 year-old Marie.

They stated that England was the country in which they now expected to reside, showing that Nellie had no intention of returning to Canada.

She gave their future address as 68 Grosvenor Road, Wavertree, Liverpool.

The 1911 Census records Nelly’s father Charles Dawson living at that address with his second wife, Margaret, nee Cunningham, and the five children she had borne him: William Edward, Ada, Margaret Gertrude, Robert Arthur and George.

Margaret had died in 1912, but we know from the attestation papers of Frederick Dawson, Nellie’s brother, by Charles’s first wife, that Charles was still resident at this address in March 1916.

So Nellie was returning with her daughter to her father’s home. It is not clear whether she was leaving Christopher or, conversely, planning to reunite with him.

She had probably left Canada before Christopher knew that he was being sent back there. Indeed she had been in England for a month before he sailed. We do not know if they saw each other before he left England.

One distinct possibility is that they had both expected Christopher to be discharged in England, so that they could be reunited there.

He appears to have followed her back across the Atlantic at the earliest opportunity, suggesting that he regarded their relationship as ongoing. Within two months of leaving England, he was once more in Liverpool, arriving there from New York on the SS St Louis on 16 January 1916.

He travelled as a British man, claiming once more to be only 33 years old and, this time, employed as a guard. His passage to Liverpool suggests that he was intent on reunion with Nellie but, curiously, though he also said that he intended to reside in England, he gave as his contact address 210 Dover Road, Folkestone, Kent.

This was, of course, very close to his former base at West Sandling. And this also appears as his home address on some of the pay forms in his service record. In one case, the address is given ‘c/o Mrs Metcalf’, while the change is annotated with initials and the date ‘25/10/15’.

This would suggest that Christopher had expected to be discharged in the UK and had arranged to reside at this address, possibly pending later reunion with his wife.

Mrs Metcalf was a cousin, the daughter of his father Robert’s sister, Ellen Dracup (1853-1934). She had been christened Nellie Fedora Wright but, in 1907, had married William Boyce Warriner Metcalfe, a pharmacist.

The 1911 Census shows them living in Folkestone, together with Ellen, who seems to have been estranged from her husband.

It seems probable that Christopher had reconnected with the Metcalfes during his time at West Sandling, no doubt visiting them in Folkestone on more than one occasion.

But it is strange that he did not immediately return to his wife. Perhaps her father had suggested he was not welcome.

There is some evidence to suggest that he did return to Liverpool, however.

His daughter Doris Marie – now going by the name Maria D Dracup, aged 8 – was admitted to the Lawrence Road Council School in Wavertree, Liverpool on 11 September 1916.

Her address is recorded as 51 Kempton Street and her parent is named as Christopher Dracup, now employed as a sailor!

This would suggest that Christopher and Doris were living together at this address, a stone’s throw from Grosvenor Road. Maybe Nellie was with them, or maybe she remained at her father’s house.

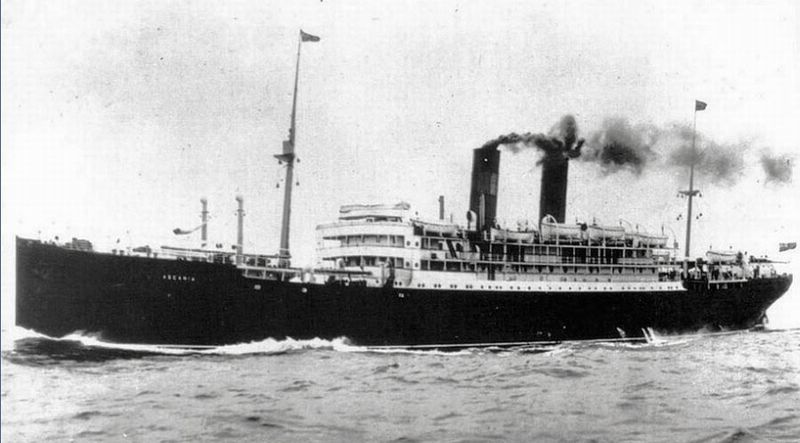

The enrolment of Doris Marie in school was quite possibly one of Christopher’s last acts in England. We know that he was on board the SS Ascania, which reached Quebec on 27 October 1916. He had spent only eight months in England.

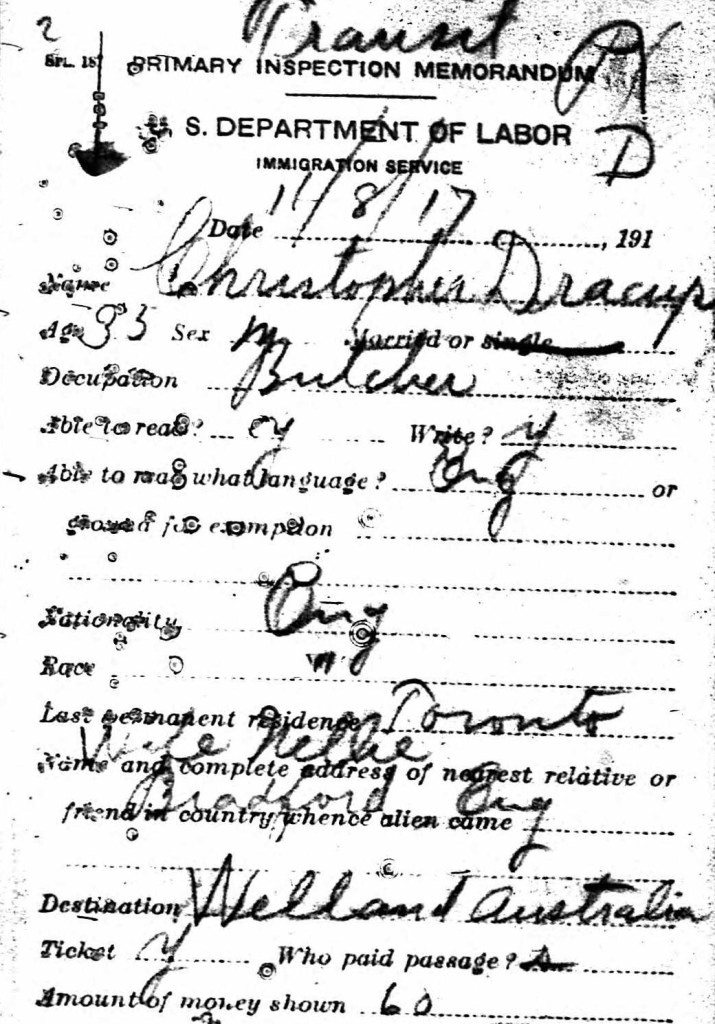

On this occasion, he described himself as a returning Canadian, having last been in Canada in 1916 and having spent 8 years there, most recently in Belleville. He admitted to English birth and his marital status, but claimed he now intended to remain in Canada. He once again claimed to have been a butcher in England, but said he would work as a labourer in Canada. His intended destination was Toronto.

Despite Christopher admitting his marriage, this was presumably a permanent rupture between Christopher and Nellie, unless she was already unwell and intended to follow him back to Canada in due course, once she had regained her health. Was she already ill when Christopher left, or did his departure hasten her decline?

If it was intended to be a permanent separation, we don’t know whether it was by mutual consent, or whether Christopher deserted his wife and child.

Tragically, Nellie died in Liverpool in May 1917, aged only 38. She was buried on 31 May 1917 in Everton Cemetery, her address given as 68 Grosvenor Road.

Doris Marie was effectively now an orphan.

Christopher’s new life

Christopher did not remain long in Toronto, although his service record states that his address, while there, was 261 Withrow Avenue.

While living at that address, he was awarded three months post-discharge pay, in three cheques dated August, September and October 1917 respectively: a total of 160 Canadian dollars and 10 cents.

But, on 11 August 1917, he had arrived in Port Huron, Michigan, USA. The record states that he was English, aged 33, born in Bradford and formerly employed as a butcher. His last permanent residence had been in Toronto. His nearest relative was his wife Nellie, then resident in Bradford England.

He didn’t intend to stay in the United States, but was en route to Welland, Australia, via San Francisco. He planned to join a friend in Welland, a suburb of Adelaide and an important Australian brickmaking centre.

Nellie was already dead by this point, so the reference to her suggests that her death had not been communicated to him. Of course, her family may not have had a current address at which to contact him. But he would have known of her death if he had been writing to her regularly.

It seems unlikely that Christopher ever departed for Australia.

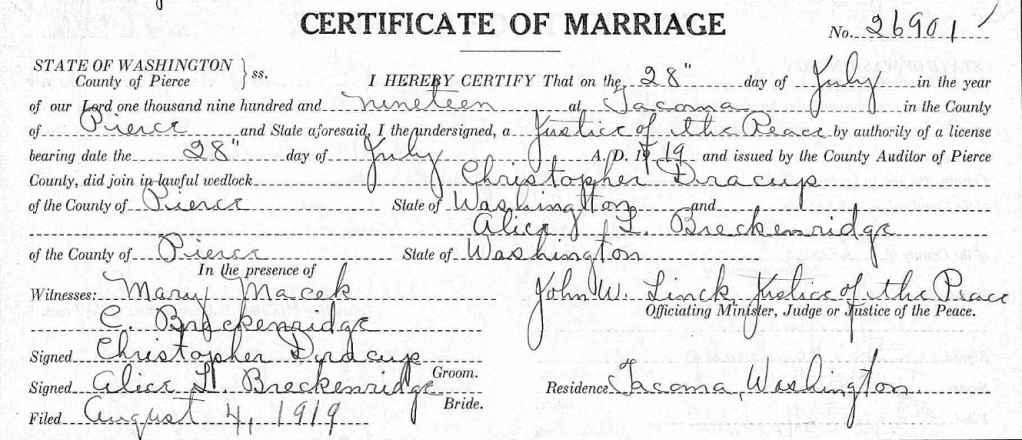

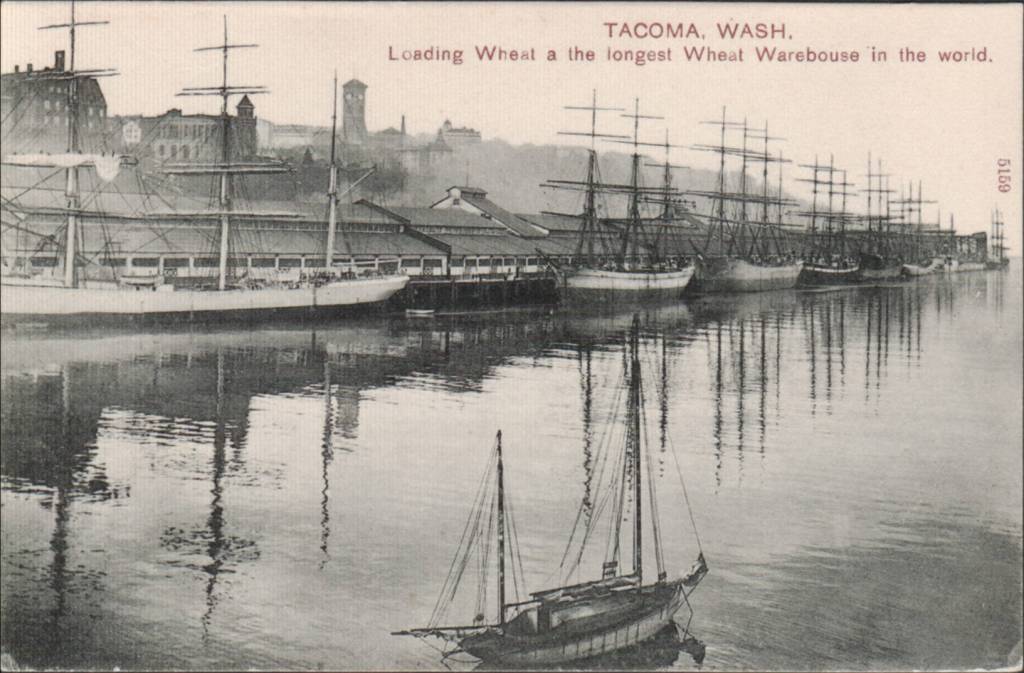

He surfaces next in Tacoma, Pierce County, Washington. On 28 July 1919, he was married there, to Alicia Leah Breckenridge. He was now 40 years old; she was 29.

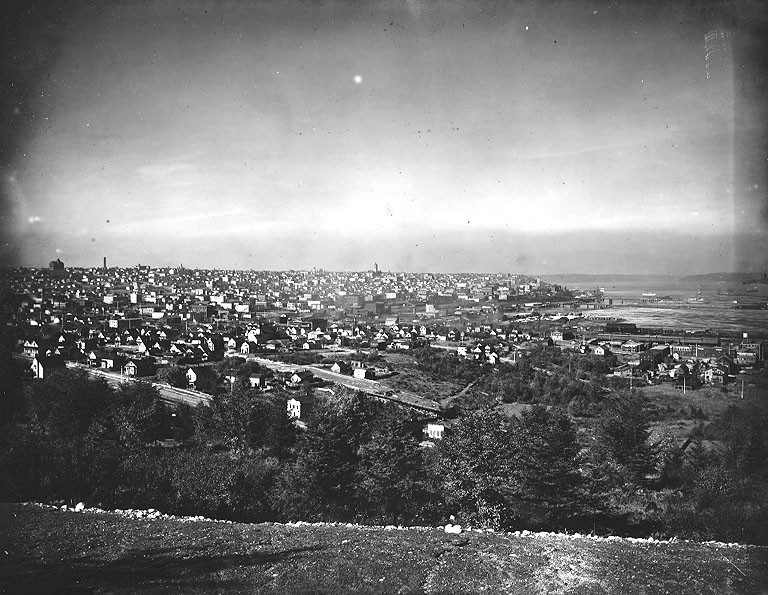

Tacoma is located on Puget Sound, some 20 miles south of Seattle. In 1883, it became the western terminus of the Northern Pacific Railroad. Over the decade from 1880 to 1890, the population increased from just over 1,000 to more than 36,000. It was a boom town, that boom driven principally by the timber trade.

The Great War brought further prosperity, especially via the shipyards, which also swallowed up more timber. The Port of Tacoma was established just after the War, but Tacoma wasn’t exempt from economic decline in the 1920s, suffering during the Great Depression.

By 1940 the population of Tacoma City had reached 100,000, with perhaps half as many again living elsewhere in the metropolitan district.

The Breckenridges

Alice was Canadian by birth, born in Northumberland, Ontario, to Palen Clark Breckenridge (1849-1935), a carpenter, and Elizabeth, nee Holmes (1849-1931).

At the time of the 1901 Canadian Census, the Breckenridge family still resided in Percy, Ontario. There were six children still alive: Grace Margaret (17), Alice Leah (13) and Charles George (10) were all still living at home. Three older siblings – Frederick Harold (29), Henry Clark (23) and William Holmes (20) – were living elsewhere.

Palen Breckenridge seems to have arrived in the United States in July 1901, but Elizabeth and her younger children didn’t follow him until 1904. They were all resident in Tacoma by 1905 at the latest.

William also seems to have migrated to the USA, since he died in Tacoma in May 1905, at the age of only 23. The 1905 Tacoma Directory reveals that he was employed as an engineer and that he was living at the same address as his father – 909 1/2 South Tacoma Avenue.

Of the two absentees, Frederick, the eldest, had already married, and he remained in Canada with his wife and young family. He died in Northumberland, Ontario in May 1904, at the tender age of 32.

The other son, Henry (1878-1951), got married at this time, to an Oregon native called Dessie Linder (1884-1974), and in 1907 was resident in Oregon, working as a teamster, when his first child was born.

Back in Tacoma, the remainder of the family quickly moved to a new home. The 1906 Tacoma Directory lists Palen, alongside Grace and Leah, now at 2114 South 41st Street, where they were to remain.

Palen and Elizabeth also became naturalised US citizens in 1906.

Charles made an early impact. A local newspaper reports that, in 1907, aged 17, he was remanded in custody in Portland, Oregon after trying to elope with Grace Nolan, a 15 year-old girl.

A few weeks previously, he had moved from Tacoma to start work in a sawmill, lodging with the Nolans who lived nearby. He promptly fell in love with Grace and, deciding that her father worked her too hard, had resolved to rescue her.

He put her on a train headed towards Tacoma, but Grace’s father had him arrested for abduction. I could not discover how exactly the matter was resolved.

By 1910 then, the Tacoma Breckenridges were settled at 2114 South 41st Street. Both Palen and Elizabeth were now aged 40. According to the Census, Elizabeth had given birth to 10 children, but only four remained alive.

Grace Margaret (26), Alice (21) and Charles George (18) were still living at home, while Henry’s children were being born in Canada, suggesting that he had returned there from Oregon.

In Tacoma, Palen continued working as a carpenter. Grace was employed in a department store and George as a trucker for a freight company. Alice had no employment at this point. She could read and write but she had not attended school.

The 1911 Tacoma Directory indicates that Charles had changed jobs, becoming a checker on the Great Northern Railway. Grace’s employment was not listed. By 1912, Charles was a clerk, still with the Great Northern Railway; Grace was also a clerk, at the Arcade Store.

By 1915, both Grace and Alice were employed as clerks. In the 1916 edition, only Palen’s employment was listed and it appears that he may have been away from home, potentially contributing to the war effort. Alice, Charles and Grace were all still residing at home, but no employment details are provided.

There is an enlistment record for Palen, dated 15 August 1917 when, at the age of 67, he joined the Washington State Guard. He was discharged in June 1918. He is described as 5 feet 11 inches tall, with blue eyes, brown hair and a ruddy complexion.

Christopher and Alice in Tacoma

The 1920 US Census places newlyweds Christopher and Alice at 2115 South 42nd Street. Their home was rented. Christopher claimed to be 34 (he was actually 41) while Grace was 31.

Christopher gave the date of his arrival in the USA as 1916, confirming that he had been born in England. He was now employed as a bricklayer with a boiler contractor.

Having once decided to make himself Bulgarian, Christopher now stated that his father was born in France, and was a French speaker, while acknowledging, truthfully, that his mother was English-born and spoke English.

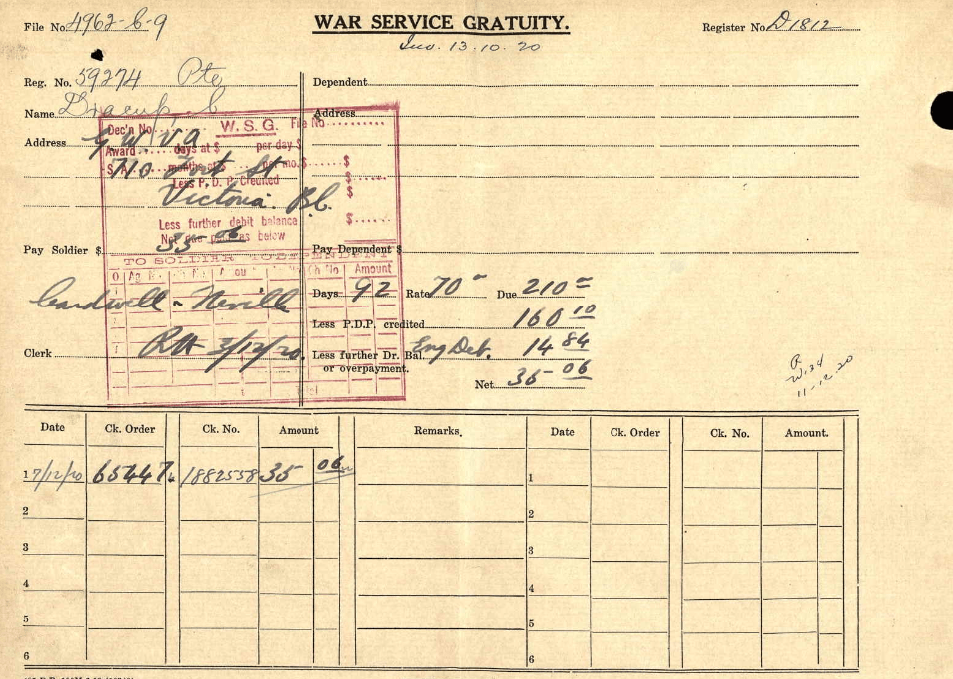

In October 1920, he submitted an application for War Service Gratuity, which is preserved in his service record. In this, he gives as his place of residence not Tacoma but ‘GWVA Rooms, 710 Fort Street, Victoria, B.C’.

This was accommodation provided by the Great War Veterans’ Association, seemingly located in the Ritz Hotel.

Since the form is witnessed by the Secretary of the Victoria Branch of the GWVA, it suggests that Christopher must have been residing there temporarily while making his application – and waiting for payment.

On the form, he stated that he enlisted in the CEF on 15 January 1914, fully seven months before the War started!

He confirmed that, while he was serving, separation allowance had been paid to his wife, Nellie Dracup, but he couldn’t now supply her address inserting: ‘At present not known, living in England.’

Had he remarried in 1919 while believing his first wife still alive? Or, more likely, was he now implying that she remained alive in order to claim a higher rate of gratuity? Men with dependents were paid at a rate of 100 Canadian dollars a month; those without received only 70.

Providing details of his service, he stated that he served for a year and two months, of which 10 months were spent with the 21st Battalion. He gave his date of discharge as 28 December 1915, the grounds being ‘medically unfit for further service…deafness’.

He claimed that he had received 99 Canadian dollars in post-discharge pay, while Nellie had received 60 Canadian dollars. (As noted above, Christopher himself received the full amount of just over 160 dollars in 1917, after Nellie’s death)

The decision is also recorded: he was judged eligible for three months’ gratuity at the lower rate of 70 dollars a month, having been on active service for less than one year, part of which was spent abroad.

However, the full 160 dollars paid out in 1917 was offset, and he was also debited a further sum, leaving a balance of just 35 dollars and 6 cents. This was paid to him by cheque on 7 December 1920.

It must have seemed a poor return, given the likely cost of his journey to Victoria and his residence there, pending the award.

Christopher appeared several times in Tacoma newspapers during the 1920s, winning prizes as a breeder and exhibitor in local poultry shows. He seems to have specialised in ‘Silver Gray Dorkings’, ‘White Dorkings’ and ‘Mottled Houdans’.

From 1923, his address is given as 2106, South 41st Street, in close proximity to his in-laws. This broadly accords with the entries in the annual Tacoma Directory, which place him at his previous address until 1922. His employment throughout is ‘labourer’.

The 1930 Census confirmed that Christopher and Alice owned this latter house, which was valued at $1,500. Christopher claimed to be 45 years old, but was actually 51. He had not attended school, though he was literate. On this occasion, both his mother and father were confirmed as English – and he too was born there.

His normal employment was ‘building labourer’, but he was unemployed – unsurprising during the Depression. He states that he is not a veteran: strictly speaking, he was a Canadian veteran, rather than an American veteran.

On 1 March 1934, Christopher completed his ‘declaration of intention’ in preparation for US naturalisation.

In this document, he gave his address as 2106 South 41st Street, but once again gave his occupation as ‘butcher’ and his age as 51 (he was 54). He is now described as five feet 3-and-a-half inches tall, weighing 169 pounds, with a dark complexion, grey eyes and black hair. No distinguishing features were identified.

He gave his nationality as British and his birthday as June 15 1882 (rather than 1879). He stated that he was married to Alice on 15 July 1918 (rather than 28 July 1919) and that he had no children. He adds that he entered the USA at Port Huron on November 8 1917.

It is possible that he feared for his status as a US resident, given that his wife Alice was dying. She had been diagnosed in 1931 with cancer of the uterus, finally succumbing on 1 July 1934.

A brief notice of her death was published in The Tacoma Daily Ledger and Tacoma News Tribune of 2 July. This mentions that she had been ill for two years, had lived in the vicinity for 30 years and was a member of the Church of God in Puyallup, some miles inland of central Tacoma.

Christopher never completed his naturalisation as a US citizen.

What became of the Breckenridges?

In 1920, Palen missed the US Census, possibly because he was temporarily across the border in Canada. However, the Tacoma City Directory for 1920 confirms his normal residence at 2114 South 41st Street. He was working at that time as a manager for William J A Simpson (though, by 1922, the entries return to ‘carpenter’).

Elizabeth, his wife, was living at 2114 South 41st Street, though sharing the property with Charles and his young family.

For, in June 1918, Charles had married Beulah Seeley, daughter of Milo Seeley, a shipping clerk, and Eva, nee Berglund. They had a four-month-old son and Charles was now employed as a stevedore at the docks.

(This is slightly confusing as, in American parlance, longshoremen work exclusively in docks, while stevedores work aboard vessels, although the vessels may be moored in the docks!)

Grace was also recorded at the same address, although she too was married by this point. It appears that she married Carl Emanuel Hoganson, a stevedore, in Ontario, Canada. The Washington marriage return states that a marriage license was obtained on 11 December 1919, but that the actual date of the marriage is unknown.

In fact, Grace has twin entries in the 1920 Census, since she is also shown as resident with Carl in a different property on 59th Street. They were living alongside Hoganson’s mother and Florence, his daughter by a previous marriage. He was now employed as a longshoreman.

By 1930, Palen and Elizabeth were reunited, at the same address, still living in close proximity to Christopher and Alice, who were placed next to them on the census form. They owned their property, which was thought to be worth $2,500. Palen was now 80 and Elizabeth 81.

Elizabeth died on 13 June 1931, of myocarditis and arteriosclerosis and was buried in the Mountain View Cemetery on 16 June. Palen died four years later, on 20 October 1935, aged 86, and is also buried in Mountain View.

As for Alice’s three surviving siblings:

- Henry and Dessie officially migrated to Seattle on 1 February 1917 but, by the following year, were resident at North Bend, Coos, Oregon. In the 1920 Census, Henry’s employment was ‘transfer man’. Within a few years, they moved again, this time to Oakland, California, where Henry was initially employed as a longshoreman and then as a miner. But the 1930 Census describes him as a stationary engineer engaged in the lumber business and, by 1940, he was a labourer working in construction. He died in Alameda, Oakland on 20 March 1951; Dessie in 1974.

- By 1930, Grace had given birth to a daughter and two sons and her husband Carl was once more a stevedore. By 1940, they had moved to Elk Plain, several miles inland from Tacoma, though Hoganson remained a stevedore. By 1950, they were at another location in Pierce County, impossible to identify, and Hoganson was a longshoreman once again. Grace died on 1 January 1953; her husband survived until 1973.

- In 1930, Charles and Beulah were still in Tacoma City, but now at 402 56th Street. Charles remained a stevedore and they now had two sons and a daughter. By 1940 they had moved to Parkland, Pierce County. Charles was a longshoreman; his wife a ‘saleslady’. (The two sons – Charles George Jr. and Richard Frederick – both served in submarines during the Second World War. At one point in 1945, they were serving together aboard the USS Aspro (SS309). Richard won a Navy Cross for closing a jammed conning tower hatch while his submarine was diving, and continued in the Navy after the War. Unfortunately, his first wife was killed in a car accident in December 1949; he was injured.) We know that Charles and Beulah had turned to bar work by 1941, because Christopher stated that he was visiting them that year, at the Tipperary Tavern in Tacoma (see below). By 1950, they were living in Mineral, Lewis County, some distance inland from Tacoma, where both worked as bar tenders. Charles died in 1976; Beulah in 1988.

Christopher’s Final years

Having lost his mother-in-law in 1931, his second wife in 1934, and his father-in-law in 1935, Christopher’s family support network was seriously depleted. He is unlikely to have inherited significant sums from his wife or his father-in-law.

In England, his first father-in-law, Charles Dawson, had also died in 1931, his Aunt Ellen in 1934. He may also have been aware of his own father’s death in 1936, though I could find no record of him returning to England for the funeral. As we have seen, he was not named in the probate record.

The 1938 Tacoma City Directory places ‘Chris Dracup’ in Apartment 15, 801 South 11th Street. No employment is mentioned.

The 1940 US Census shows that he had moved again, somewhere in the vicinity of South 7th Street, in Ward 2 of the City. He rented his home, the value of which was just $15 – surely little more than a shack. In 1940, the median home value in the US was $2,938.

He had evidently come down in the world since the death of his wife and her parents. He was working an average of only 18 hours a week as a hod carrier in building construction. He had been employed for 18 weeks that year, accruing a total income of $600, less than half of the average US household annual income.

He gave his correct age – 61 – but said he was single rather than widowed. His birthplace was in England, and he had his first citizenship papers.

He must have departed for Canada shortly afterwards. On 5 February 1941, he returned to the USA, arriving in Seattle on a Canadian passport. The record suggests he had crossed to Vancouver some six months previously, in June 1940.

He had been working there temporarily, employed by J Grieves, at 620 Nanaimo Street, and living at 520 Richards Street. He had no relatives in Canada.

He gave his correct age, birthday and place of birth, but said his nationality was Canadian and that he had arrived in the US previously in 1919, rather than in 1917. He was described as five feet five-and-a-half inches tall, with a medium complexion, black hair and grey eyes.

He claimed to be visiting his ‘stepbrother’ (actually his brother-in-law), ‘Charles Breckinbridge’ [sic], for one to two weeks, at the ‘Tipperary Tavern, Scales and Park Avenue, Tacoma’. (This now seems to be known as the Hard Luck Bar and Grill, located at 10713 Park Avenue South.)

After that, Christopher’s life fades into obscurity, though we know he was still in Canada. In the 1949 Canadian electoral list there is a Mr C Dracup, a salesman, living at 1011 Centre Street, Welland, Ontario.

In the 1958 electoral list, Mr C Dracup, a salesman, is living in an apartment at 347 Homer Street, Vancouver. The death notice, published in the Vancouver Sun, places him at 347 West Pender Street. This is on the corner of Homer Street and West Pender Street, which leads me to conclude that ‘Mr C Dracup’ was indeed Christopher.

We do not know what he had been selling but, assuming this was Christopher, he was still working at the age of almost 80.

The death notice says little more, other than that he had died in hospital on 9 January 1961, that the funeral service was to be held on 11 January at Kearney’s Broadway Chapel, and that he was to be interred in the Veteran’s Field of Honour at the Forest Lawn Memorial Park.

So ended Christopher’s long and colourful life: he was 81.

Doris Marie Dracup

We left his daughter, Doris Marie, in May 1917, ostensibly an orphan. One might perhaps have expected Charles Dawson, her grandfather, to take her in, or perhaps one of Nellie’s brothers, but I can find no evidence that this occurred.

For, in the 1921 Census, she appears on the roll of an institution called ‘Cottage Homes (Camp)’, located in Ainsdale, near Southport, Merseyside. The record says she was 11, but she was actually 13. There are many other girls attending, mostly aged between 5 and 13.

I have been unable to recover any details of this establishment, though my best guess is that it was essentially an orphanage, probably an outpost of the Wavertree Cottage Homes established at Olive Mount, near Wavertree, in 1901.

The West Derby Union, which administered the Poor Law in the Wavertree area, had opened the first such ‘cottage homes’ in Fazakerley, Liverpool, in 1889. They provided residential care for children in groups, like large families. Each group, maybe 15-25 strong, lived in a house alongside ‘house parents’: a married couple who had been trained for the role.

The model reached its peak in the early 1930s, when it is estimated that some 15,000 orphans were cared for in this way, across England and Wales.

Meanwhile, her grandfather was still living at 68 Grosvenor Road, Wavertree, just across from the Grosvenor Hotel. According to the 1921 Census, he was still a waiter, but now worked at the Exchange Hotel. The other residents were his daughter Margaret Gertrude, now aged 25, and his son George Albert, aged 15. Margaret, his wife, had died in 1912.

By 1924, electoral registers also place his son Frederick in the house.

Charles died on 18 August 1931, aged 74, the cemetery register giving his address as 68 Grosvenor Road. Meanwhile, Frederick had married in 1928 and seems thereafter to have resided in Southport. He died there on 8 February 1938.

Doris finally reappears in 1931-32, in the electoral registers for Toxteth, Liverpool. Now 24 years old, she was living in a property called Mossley Bank, on Elmswood Road, in the Aigburth area. There were five residents, all female. By 1934-35, she was living in the Vauxhall Ward, again in a shared property.

But then, in October 1936, she married George Albert Dawson (1906-1954), her mother’s half-brother, son of Charles Dawson by his second wife. No doubt she remembered him as a convenient playmate during her childhood years in Wavertree.

Electoral registers show that George had been living at 68 Grosvenor Road since 1932-33, having presumably taken over the house from half-brother Frederick when he moved to Southport.

In an amazing twist of fate, Doris moved into what had been briefly her childhood home, her mother’s and her grandfather’s home: a home that she seems to have lost upon her mother’s death.

The 1939 Register places George and Doris at this address. George was working as a painter’s labourer. They have a son, Leslie Arthur Dawson, born on 14 February 1937 (so Doris was pregnant when they married). A daughter, Edna, was born in 1941.

After George’s death, at the age of just 48, Doris lived on at 68 Grosvenor Road, remaining there until at least 1970. She died in 1983.

As far as I can establish, following his departure for Canada in 1916, Doris never saw her father again.

TD

September 2023

Leave a comment