We come full circle with this 12th and final post in my Ouroboros series, each exploring a piece of music that is personally important to me.

Last time round I gave the game away, explaining that I’d been unable to choose a single composition by Franco et le TPOK Jazz. There had to be at least two.

For Ouroboros 11 I chose ‘Tres Impoli’, originally from the album of the same name, released in 1984.

This final episode is dedicated to ‘Sadou’, alternatively called ‘Batela Makila Na Ngai’. It was originally released on the album ‘La Reponse de Mario (On entre O.K. On Sorte K.O.)’ which issued in 1988, a year before Franco’s death.

I came to know and love it as the final track on ‘Francophonic, Vol. 2’, the superb compilation released by Stern’s Africa in 2009.

I’m the first to admit that this is an idiosyncratic selection. Why choose a song by your favourite guitarist of all time on which his guitar playing is negligible?

Well, I suppose the answer has two parts: first, Franco has already demonstrated his skill as a guitarist on my previous selection; second, ‘Sadou’ is brimful of bittersweet melancholy, as if le Grand Maitre knew that he was close to the end of his stellar career.

Ouroboros 11 set out the details of Franco’s life and musical career, up to the point where ‘Tres Impoli’ was released. Before considering ‘Sadou’ in more detail, it is necessary to complete that story.

Franco’s final years

1985 saw the release of ‘Mario’, probably Franco’s most celebrated track and one of his biggest hits, selling over 200,000 copies in Zaire alone.

It deals with the trend, then establishing itself in Zaire, for older women to support younger men financially in return for sexual favours. It describes the growing dissatisfaction of such a woman with her young gigolo, who is unemployed, lazy and abusive.

Franco and TPOK Jazz returned that year to the United States, playing the Manhattan Center in New York, and to London, where they performed at the Africa Centre.

And, at the end of August, in a nod towards Live Aid, Franco organised two concerts in Ivory Coast, to raise money for African famine victims. Mobutu supplied the plane that flew his 31-strong touring party into Abidjan.

There were further departures of prominent band members. Dalienst left in 1984, forming a band called Orchestre Saka Saka in Brussels. In 1986 he recorded an album with Josky, who had also left TPOK Jazz by that point. Simaro also recorded his own album, independently of Franco’s musical empire.

Both Josky and Dalienst were to return, Dalienst from time to time and Josky permanently in 1987. But Franco also recruited new vocal talent in the form of Malage de Lugendo and Jolie Detta, the latter from Tabu Ley’s Afrisa.

An album, ‘Le Grand Maitre Franco et son Tout Puissant O.K. Jazz et Jolie Detta’, included ‘Layile’ and ‘Massu’, which were both notable additions to the TPOK canon.

There were two major tours of Kenya, in 1986 and 1987, reflecting the growing Kenyan audience for Franco’s music. This built on their first major exposure, in 1982/83, during Kenya’s 20th anniversary celebrations.

In 1987 Franco recorded ‘Attention Na Sida’, which dominates an album of the same name. It was recorded in Brussels with the band Victoria Eleison, led by vocalist Kester Emenya (1956-2014), and sung in a combination of French and Lingala.

It is a powerful public health message, warning of the dangers of AIDS, educating people about how the disease was spread and urging their governments to fight the epidemic.

With delicious irony, Franco recycled some of the arrangements and guitar solos from ‘Jackie’, one of the songs condemned for immorality that had led to his imprisonment in 1978.

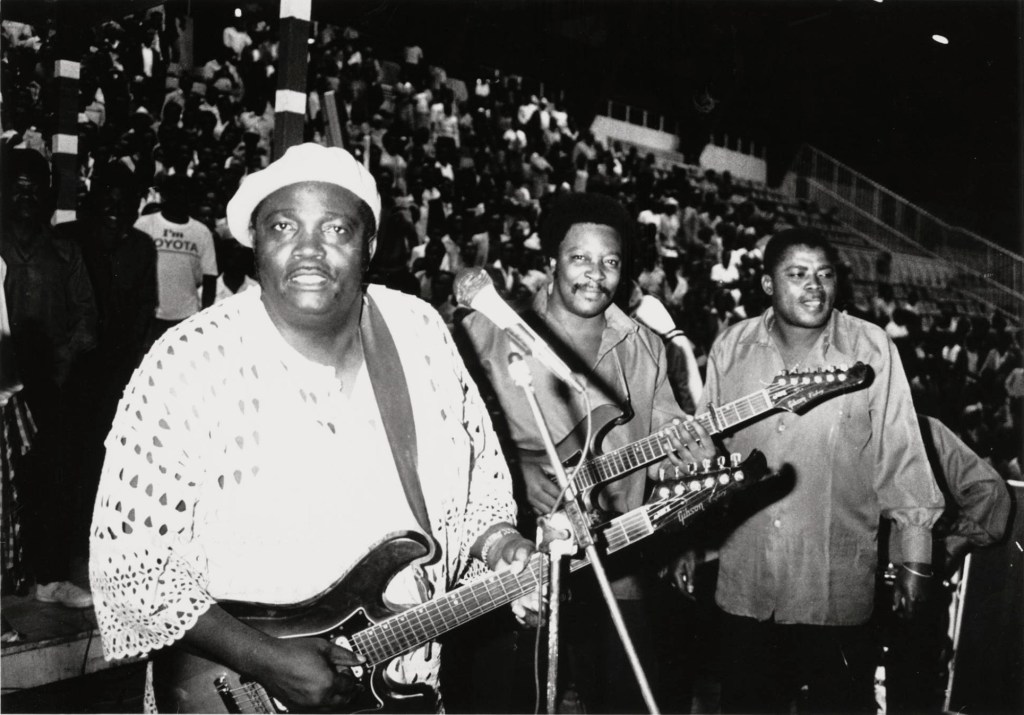

That May, he appeared with TPOK Jazz at the Africa Mama Festival in Utrecht. A ‘Live En Hollande’ album followed in 1987 (and, ironically, in 1990, a second called ‘Still Alive’). This turned out to be the final concert that Franco played in full health, alongside a band of 28 musicians, eight of them guitarists.

By the beginning of 1988 though, Franco’s health was becoming a cause for concern. He underwent a series of tests to diagnose the problem, but always maintained that his illness could not be established.

It was at exactly this time that ‘La Reponse de Mario’ appeared. The title song is a follow-up to ‘Mario’, giving the gigolo’s response to the complaints of the woman who is keeping him. Sadou was the second of four tracks on the album.

Franco now made few public appearances and, when TPOK Jazz performed, would only appear on stage for a few minutes at a time. In the absence of denials, or statements to the contrary, rumours began to spread that he had contracted AIDS. It became known that he had converted back to Roman Catholicism, having turned to Islam earlier in his career.

Some have even alleged that, after visiting Franco at his home, it was actually Madilu who let slip that Franco was dangerously ill. If he did so, I’m sure it was out of concern for his band leader and, in any case, he must have been confirming what had now become painfully evident.

But, in November 1988, Franco recorded ‘Les Rumeurs’, hitting back at those who gossiped about his health behind his back:

‘Ebele ya malade bokabeli ngai na nzoto baninga

Nasala nini na mokili

Nzambe asala moto po abotama

Nzambe asala moto pe azua malade

Ya ngai sango epanzani mokili mobimba

Nasala nini oo’

‘My body has been burdened by illness

What in the world have I done?

God created man to be born

God also created man to grow sick

But when it happens to me, the news travels all over the world.’

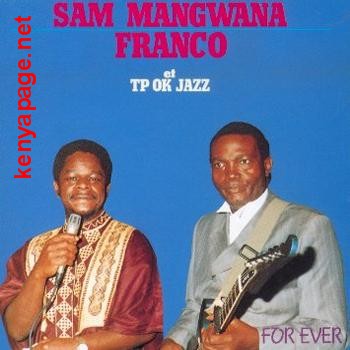

Three months later, in February 1989, he completed his final recordings for an album ironically titled ‘For Ever’.

This latest collaboration with Sam Mangwana showed the pair on its cover. Franco, who had been growing seriously overweight, was now painfully thin, literally a shadow of his former self.

He performed briefly at a handful of concerts that September, the last on 22 September in Amsterdam. The next day he was admitted to a Belgian clinic, where he died on 12 October 1989, aged only 51.

Following his funeral, President Mobutu declared four days of national mourning in Zaire.

His influence on Congolese and pan-African music had been colossal and, for over thirty years, he had been a truly prolific musician and composer. This continued posthumously.

Calculations vary, but Discogs lists 92 original albums, plus a further 120 compilations. He is estimated to have written over 1,000 songs during his lifetime.

Sadou

So why have I chosen ‘Sadou’ above all of those?

Well, not so much for the lyrics which, though they sound beautiful in Lingala, are hard to render meaningfully in English.

And not really for the music either, because we hear so little of Franco’s superlative guitar-playing.

Perhaps for the overall ‘ambience’, which captures a crisis point in Franco’s life and career. For this was recorded exactly when this powerful man, still at the peak of his musical powers, was having to confront his own mortality.

The performance is stripped down. There isn’t a huge cadre of exceptional supporting musicians; only Franco and Madilu, taking verses in turn and harmonising the chorus together over a backing track that is predominantly synthesised.

Even the horns sound slightly too perfect, as if they too have been programmed into a synthesiser.

But the short chorus is beautifully balanced, both as a piece of verse, and also between these two complementary male voices: Madilu, with that trademark ‘tremulous vibrato’, fragile and achingly beautiful; and Franco with his deeper, echoing baritone, more masculine and authoritative, yet perhaps now beginning to express the tiniest hint of vulnerability.

It is the voice of a man who is used to being obeyed, who is just beginning to realise that he may be seriously ill, but who is trying desperately not to think too much about that.

There is an element of impending doom; a Sword of Damocles suspended above his head.

The chorus runs:

‘Batela makila na ngai, batela bolingo na biso,

Batela mondenge tobetaki, Sadou.’

Translated into English, with a little added poetic license, that means something like:

‘Protect my bloodline; hold safe our love;

Keep the promises we made each other, Sadou.’

The verses are spoken by a man who is reflecting on his past life with Sadou. There is a strong element of nostalgia, and it may be that he is leaving her, possibly dying.

It seems that the rest of the world has been against them from the start, gossiping, spreading false rumours and lies. He alleges that they even paid other men to tempt Sadou away from him.

He has faced constant criticism from others, whether for drinking and smoking, or earning too little money from an unskilled job. But he has made progress in the world, and her faith in him when he was poor has been justified.

The final part of the song is strange, cynical and negative.

‘Why is it that, when you know you are beautiful, you can get all you want?

Better to hide it, for remember that beauty fades.

Though you have children, you’ll have no means to raise them.

Then you will have to beg at people’s doors,

Your slippers ragged; your feet full of dust.

You are a woman – they will mark you.

Dance this song with some purity; it is not just a secular song.

The last breath of a sick man has just expired.

It is unclear whether the singer is imagining Sadou as she may be after his death. But the penultimate line apparently implies that this song has almost religious significance, possibly written to be performed at a ceremony, such as a funeral.

And the final line is positively Shakespearean, carrying within it a triple meaning: the man whose words these are is sick and has just breathed his last; the singer himself has expelled his final breath (ie completed his song); and the singer himself is sick.

Musically, the composition begins with a very simple, eight note melody repeated three times on Franco’s guitar, one of his characteristic humming sounds appearing between the first and second. (For the connoisseur of Franco’s hums, there are several to be found in this song.)

A drumbeat is introduced just as the third repetition ends. This introduces the ten-note synthesiser refrain that runs through the entire song. It has a jolly, benign, lilting quality, quite distinct from Franco’s more usual sonic textures.

Madilu takes the first verse, solo, which concerns itself with the spreading of lies and false rumours. Then the first use of the chorus, harmonised and twice repeated, before one of them weighs in with the second verse, the chorus twice repeated, and so on.

During Madilu’s second verse, Franco joins in after his first line, singing the rest of that verse behind him’ He relates how the spreaders of false rumours now seem embarrassed, Franco adding an emphatic ‘c’est vrai’ in the middle. Then we’re into the third pair of harmonised choruses.

After this, we get a small break, at around 2 minutes 30 seconds, when the synthesised horns play their own refrain, twice over. It is sweetly melodic, almost saccharine, and superimposed over the basic 10-note opening pattern.

Franco intersperses a ‘Somo’ before the end of the second iteration, adding ‘so unfortunate, the tale of Sadou’ which leads Madilu into his next verse. This is begun solo, but Franco joins in with alternate lines.

Following the fourth pair of choruses, Franco takes a verse. This is perhaps the sketchiest in the song, as he struggles to fit the final line into the small space available (it is something cutting about shoes) before the beautiful double chorus comes to the rescue.

They’re both clearly enjoying proceedings at this point, with Madilu in full tremolo, Franco emitting sounds of pleasure between the first and second choruses.

After which, it’s Madilu’s turn to take the verse again, repeating the same quatrain with which he began the song. Franco emphasises certain phrases by singing behind him, but we’re soon into the next pair of choruses, Franco exuding a huge ‘mmmhh’ between them.

Now it’s his turn to take the verse again, and he’s much more in control of this one, berating the women who have cast aspersions, who are now, themselves, poverty-stricken.

Two more choruses, then Madilu begins to repeat his second verse from earlier. And this pattern is repeated, as Madilu launches into his third verse for the second time, against a current of laughter.

Franco reinforces a line about their accusers not knowing that the world might change the very next day. It feels as though the second, more sonorous chuckle has been overdubbed – perhaps the only occasion where the natural unrehearsed style falters.

Two more choruses, and then the synthesised horns break in again, just after Franco has launched into his final tirade with ‘Ohh, nyoso nini…’ He continues this over the top of the horns.

The faux horns continue playing after he has finished but, once they have ended, he adds his exhortation to dance the song with some purity. Then there is a further pause before he makes that final gnomic utterance.

It seems not to be part of the song. Instead, it feels like Franco’s own message to us, his audience. Perhaps it was a premonition or prediction of his death, which came about almost exactly a year later.

‘Sadou’ is an insidious little song. On hearing it first, one might condemn it as lightweight and schmaltzy. Sonically speaking, the music is undoubtedly sentimental.

But listen enough times and that peerless chorus will ultimately weave its magic, only to be punctured by the sharp wit of Franco’s ambiguous parting shot.

Taken together, ‘Tres Impoli’ and ‘Sadou’ are a fitting testament to his genius. He wasn’t always the most likeable man, but he was a brilliant musician.

The sequence in full

That ends my Ouroboros cycle, which has featured the following compositions:

January: ‘Ya Jean (Remix)’ by Madilu System

February: ‘Autorail’ by Orchestre Baobab

March: ‘Sweet Fanta Diallo’ by Alpha Blondy

April: ‘Blue Sky’ by the Allman Brothers Band

May: ‘Saturday Night’ by The Blue Nile

June: ‘Ev’ry Time We Say Goodbye’ by Ella Fitzgerald

July: ‘Thinking of You’ by Sister Sledge

August: ‘Black Diamond Bay’ by Bob Dylan

September: ‘Different Drum’ by the Stone Poneys

October: ‘Cantique’ by Kanda Bongo Man

November: ‘Tres Impoli’ by Franco et le TPOK Jazz and now

December: ‘Sadou’ by Franco et le TPOK Jazz

Here’s my Spotify playlist containing all twelve selections.

If you are under 30, all of this music was composed before you were born.

If you are closer to my age, I hope I’ve encouraged you to listen afresh to some things you’d forgotten and, hopefully, to listen anew to some that you’d never heard before.

TD

December 2025

Leave a comment