Here is the penultimate post in this series of twelve, each exploring a musical composition with particular personal significance.

Each choice is connected in some way with its immediate predecessor. My final selection will connect with the first.

I haven’t pre-planned the steps in this sequence, so they partly reflect my preferences and predilections when I come to make each choice.

Earlier this month I set aside my preliminary selection in favour of another. I was intending to write about ‘Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes’ by Paul Simon, from the ‘Graceland’ album.

But, foolishly, and against my better judgement, I found myself listening to potential candidates for the subject of my twelfth and final post instead.

Ultimately I decided two points: first, ‘Diamonds…’ doesn’t compare with the very best of Franco et le TPOK Jazz; second, it is impossible for me to do justice to the peerless Franco through only one piece of music.

So there’ll be two.

And, indeed, I’ve had grave difficulty in narrowing myself down to only two, such is my current predilection for his music.

But, ultimately, and after much internal wrangling, I‘ve chosen, as the first of those two, ‘Tres Impoli’, originally from the album of the same name released in 1984.

The connection between this and last month’s selection, ‘Cantique’, lies in the fact that Dewayon, who was the brother of Kanda Bongo Man’s uncle (and therefore also his uncle, presumably) was an early mentor to the young Franco.

Franco’s early years

Francois Luambo Luanzo Makiadi was born on 6 July 1938 in Sona-Bata, roughly 80km south of Kinshasa, in what was then Bas-Congo province.

His father was Joseph Yvon Emongo Luambo, a railway worker, and his mother Helene Mbongo Makiese. They had three children together: Franco Luambo, Bavon Siongo Luambo (1944-1970) and Marie-Louise Akangana.

A further child, by a different father, was born while Emongo was in prison, and two more by a third man after his death in 1949.

The family moved to Kinshasa when Franco was just a few years old, and his younger siblings were born there. They settled initially in the district of Dendale, now Kasa-Vubu, living on Avenue Opala.

Franco attended the Leo II School in the Kintambo district, completing 3rd grade, but his education was effectively terminated by the family’s poverty following his father’s death.

He became interested in the evolving sound of Congolese Rumba, inspired by the guitar playing of Zacharie Elenga (1926-1990) (aka Jhimmy le Hawaïenne) and the singer Joseph Kabasele (1930-1983) (aka Le Grand Kallé).

He learned to play the harmonica, joining a group of local street musicians. Then, through an acquaintance, his mother managed to secure him a job at Ngoma Records, packing shellac discs for distribution.

Ngoma, founded in 1948 by the Greek Nicolas Jeronimidis, had a recording studio adjacent to their warehouse. Franco is said to have taught himself the elements of guitar playing on instruments left there by musicians.

This job came to an end in 1950, when the family relocated to the Rue de Bosenge in the Ngiri-Ngiri district. They rented their home from the family of Paul Ebengo Isenge (1934-1990) (aka Dewayon).

Dewayon, then only 16 himself, had a homemade guitar, on which the 12 year-old Franco learned his first chords. A little later, both boys came under the influence of Albert Luampasi (1932-1988), who had connections with Ngoma Records but also lived in Ngiri-Ngiri.

Luampasi encouraged both Franco and Dewayon, inviting them to rehearsals and performances of his group, Bandidu (some say Bandibu), which Franco eventually joined in 1952, at the age of 14.

They performed at local parties and funerals, even embarking on a lengthy tour of Bas Congo province.

Luampasi went on to record two discs for Ngoma Records: ‘Cherie Mabanza/Nzola Andambo’ and ‘Ziunga Kia Tumba/Mu Kintwadi Kieto’. Franco is said to have taken part in rehearsals but did not play in the studio.

At around the same time Dewayon formed his own band, Watam, which Franco also joined. In February 1953 they auditioned for Loningisa Records, founded in 1950 by the Greek brothers Athanase and Basile Papadimitriou.

The audition was held before Henry Bowane (1926-1992), the guitarist who had co-written and recorded the huge hit ‘Marie Louise’ with Wendo Kolosoy in 1948 for Ngoma. While Kolosoy had remained with Ngoma, Bowane had defected to Loningisa.

Watam recorded ‘Nyekese/Bolingo Ayeli Kobota’ in February 1953, possibly with Franco on guitar. Around this time, Bandidu/Bandibu and Watam performed together on stage at the Kanza Bar in Ngiri-Ngiri.

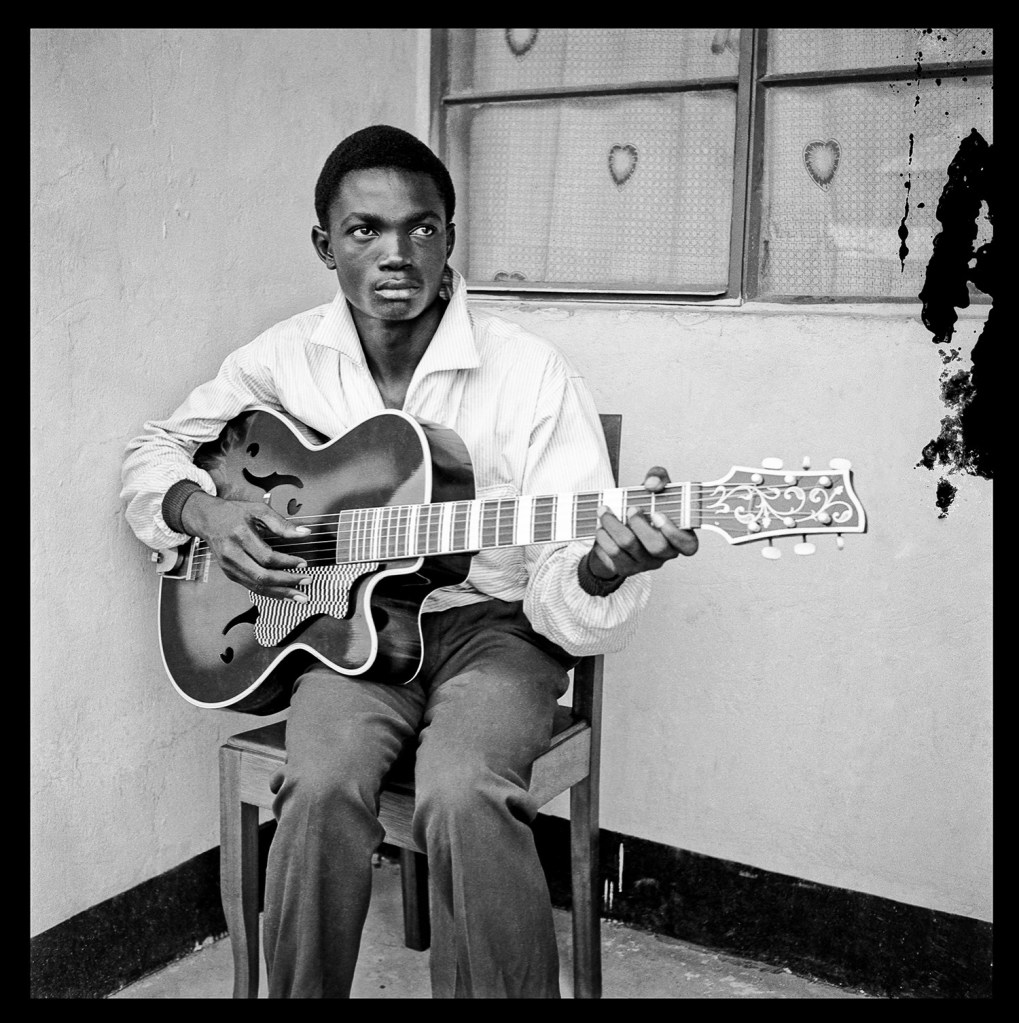

In August 1953, Franco the joint owner of Loningisa, Basile Papadimitriou,who signed him to a contract on the strength of his audition. According to Franco mythology, he was also given a proper guitar which he nicknamed ‘Libaku ya nguma’ (‘the head of the boa’) on account of its prodigious size.

Further recording sessions took place in August, October, November and December that year, Franco quickly getting to grips with his new guitar. At the November sessions he recorded his first two compositions: Kombo Ya Loningisa/Lilima Dis Cherie Wa Ngai’

The following year, 1954, Bowane established a house band for Loningisa records, LOPADI (short for ‘Loningisa de Papadimitriou’), in which the youthful guitarist featured, freshly anointed with his moniker ‘Franco’.

LOPADI metamorphosed into a looser collective known as ‘Bana Loningisa’. Other members included singer Philippe Lando (1935-2004) (aka ‘Rossignol’ or ‘Nightingale’), bass player and rhythm guitarist Daniel Lubelo (1934-2006) (aka ‘De La Lune’), singer Edouard Nganga (1933-2020) and percussionist Nicolas Bossuma (c. 1930-1990) (aka ‘Dessouin’).

In October 1955, Franco and Rossignol together recorded ‘Bayini Ngai Mpo Na Yo/Marie-Catho’, both composed by Franco. This disc became a hit, which opened the floodgates, as Franco performed on numerous other Loningisa releases in the final months of 1955 and the first half of 1956.

OK Jazz

In June 1956, Gaston Kassien, aka Oskar Kashama, who owned the O.K Dancing Bar, began to engage several musicians from Bana Longinisa to perform there on Saturday evenings and Sunday afternoons.

He also supplied the band’s instruments and a rehearsal space. So, in homage to him and his bar, they called themselves ‘OK Jazz’.

Initially some ten musicians were involved, eventually resolving to a core of seven, namely Franco, Loubelo, Rossignol, Dessouin, plus Vicky Longomba (1932-1998), Saturnin Pandi (1932-1996) and Jean Serge Essous (1935-2009). It was the clarinettist Essous who emerged as leader.

The first OK Jazz recordings date from 20/21 June 1956: ‘Makambo Mayiza Mazono/La Rumba OK’. Several other singles followed, including ‘On Entre OK; On Sorte KO’ which soon became the band’s anthem.

Towards the end of 1956, the first of many changes in line-up occurred when several musicians defected from Longinisa to Esengo, a music publishing business established by another Greek businessman Dino Antonopoulos, who had recruited Bowane to be his artistic director. They included Essous, Rossignol and Pandi. These musicians formed the basis of Orchestre Rock-a-Mambo.

As a consequence, Vicky Longomba became the band leader of OK Jazz, while Franco, still only 18, became the undisputed lead guitarist and putative musical director.

Though still a teenager, he was already acknowledged as one of the leading Congolese guitarists, an undisputed master of the ‘sixth’ technique, which involved plucking several strings simultaneously.

Following a tour and a prolonged stay in Brazzaville, OK Jazz returned home in 1958, whereupon Franco was briefly imprisoned by the colonial authorities, some say for repeatedly speeding on his Vespa scooter, others for driving without a license.

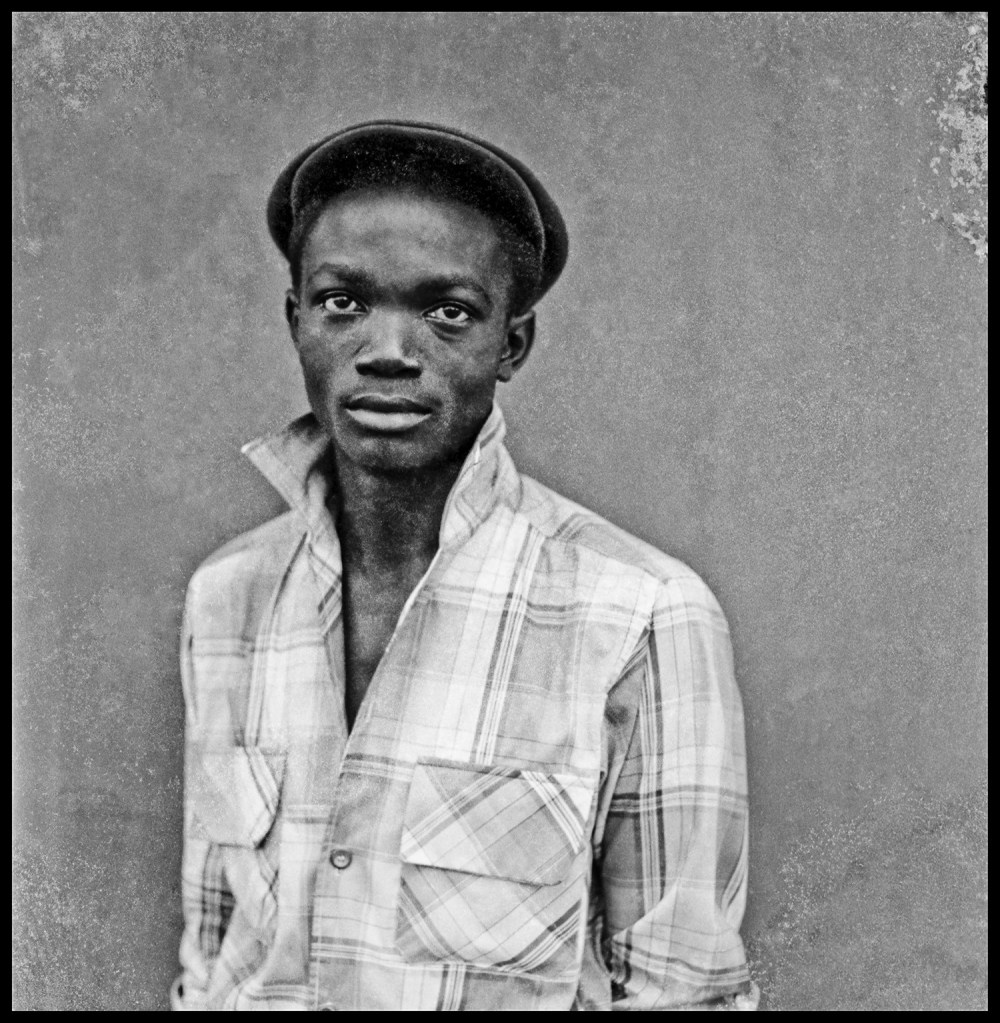

This did no harm to his burgeoning reputation with fans. Journalist Jean Jacques Kande (later Information Minister under Mobutu) described him at this time:

‘Not a pretty boy. Slightly taller than average. Eyes the colour of fire, sometimes laughing, sometimes dreaming. Hair cut away to give his physiognomy a very combative air. Very dark skin…Leopoldville number one guitarist who makes the hearts of women spin.’

In 1959 there was a second exodus of musicians from OK Jazz. Those who left formed Les Bantous de la Capitale. Vicky Longomba also departed for a while, joining Joseph Kabasele in Brussels.

OK Jazz began to withdraw from its contract with Longinisa, which was apparently struggling with the new 45rpm format, finally closing in 1962. But one of his childhood heroes, Joseph Kabasele, invited Franco and OK Jazz to record in Brussels for his Surboum label.

Inspired by this experience, Franco created his own Epanza Makita label in 1961.

Rhythm guitarist Simaro (1938-2019) joined OK Jazz in 1961, Longomba returned in 1962 and saxophonist Verckys arrived in 1963.

This was a period in which the band toured frequently and recorded prolifically. They had fully embraced a ‘rumba odemba’ style, built around muscular, rhythmic, repetitive patterns, often incorporating a traditional flavour.

The full ensemble might include: half a dozen vocalists; a seven-piece horn section; a rhythm section comprising bass, drums and congas; and, last but not least, three guitars (lead, rhythm and mi-solo) weaving complex interlocking patterns.

The culminating sebene would invariably feature Franco’s plucking technique, his guitar repeating riffs ad nauseam, building layer upon layer of rhythmic syncopation.

In 1965, Mobutu infamously instigated the public hanging of five political opponents. Franco’s song ‘Luvumbu Ndoki’ was interpreted as critical of Mobutu, who had the record banned and all copies destroyed. Franco was detained and questioned, after which he had to lie low in Brazzaville for several months.

In 1967, Franco officially assumed joint leadership of OK Jazz alongside Longomba but, that April, there was significant disruption when several band members defected to form Orchestre Revolution. This proved a relatively short-lived affair and some of these musicians later returned.

But Franco’s relationship with Verckys also became strained, not without justification, leading to Verckys’s ultimate departure in 1969.

OK Jazz were now vying for supremacy with L’Orchestre African Fiesta, led by Tabu Ley and featuring guitarist Dr Nico. These were the two leading bands of Zaire.

TPOK Jazz

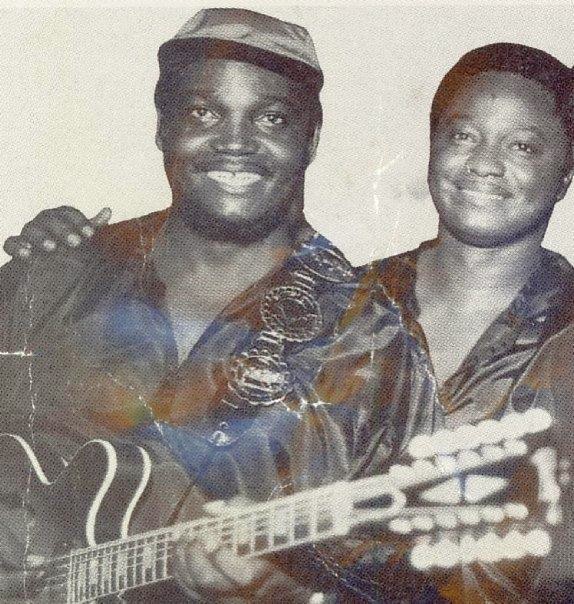

In August 1970, Franco’s brother, Bavon Siongo Luambo (aka ‘Bavon Marie Marie’) was killed in a car crash.

He was guitarist with Orchestre Negro Succès, which was initially set up as a vehicle for Vicky Longomba. It was relaunched towards the end of 1964, with support from Franco, on condition that Bavon became part of the line-up.

From 1967 onwards, Negro Succès had several major hits and, for a while, threatened to disrupt the ascendancy of OK Jazz and African Fiesta. They embraced contemporary youth culture, including the fashion for bleaching one’s skin, which ran completely counter to everything Mobutu’s ‘Authenticité’ movement stood for.

But, having quarrelled violently with his lover, who he suspected of infidelity, Bavon drunkenly smashed their car into a stationary vehicle, killing himself and injuring her so severely that she had to have both legs amputated.

Franco later composed ‘Kinsiona’ (‘Sorrow’) in memory of his late brother.

Meanwhile, Mobutu’s ‘Authenticité’ campaign was in full swing and OK Jazz were commissioned to write an anthem for the Association Zairoise d’Automobiles, formerly DIFCO (Distribution Frigorifique et Commerciale de Congo) which distributed Volkswagen cars.

As part of the deal, Franco secured vehicles for several band members, even using the cars to bribe at least one new member to join.

The resulting song, ‘Azda’, was a huge pan-African hit, featuring the punning refrain ‘ve-we, ve-we, ve-we’ (VW, VW, VW) and some heavyweight Franco guitar riffs.

However, this led to Longomba’s second departure, because he disapproved of the deal and was wary of the Band being used as Mobutu’s political instrument.

Consequently, Franco became undisputed band leader and, in 1971, renamed the outfit ‘Tout-Puissant Orchestre Kinois de Jazz’ (‘the Almighty Kinshasa Jazz Orchestra’), invariably shortened to ‘TPOK Jazz’.

Franco seemed strongly supportive of ‘Authenticité’, accompanying Mobutu on tours around the country, writing songs and producing albums in celebration of his President.

All of which did him no harm at all.

In 1973 he was appointed director of Zaire’s national musicians’ union, UMUZA. Then, in 1974, he also acquired control of the Kinshasa record-pressing plant known as MAZADIS (Manufacture Zairois du Disque), the only one in Zaire.

It had been nationalised, but the ownership was transferred to Franco, who ensured that his own recordings had priority over those of rival bands.

Franco controlled his ever-expanding empire from offices above his Un-Deux-Trois Club, which also opened in 1974, soon becoming the epicentre of the Kinshasa music scene.

There were those who claimed, not without justification, that Franco had acquired all his influence from Mobutu, and used these positions in Mobutu-like fashion, to advance his own interests and suppress the careers of potential rivals.

Indeed, Franco became one of the wealthiest men in Zaire, owning a substantial amount of property there, as well as in Belgium and France.

There were more songs in praise of Mobutu and national tours to support the President.

Yet, as the dictatorship became increasingly plagued by economic mismanagement and corruption, some of Franco’s songs also began to contain indirect but nevertheless biting social observation, which could be interpreted as oblique criticism of the regime.

Several important musicians joined the Band during these years, including Josky Kiambutuka in 1971, Sam Mangwana in 1972 and Wuta Mayi in 1974. And, during this period, Simaro was appointed the Band’s ‘chef d’orchestra’.

By the time they reached their 20th anniversary in 1976, TPOK Jazz were unrivalled in Zaire and probably the most celebrated band throughout African continent. Their reputation had been bolstered by pan-African tours and huge concerts in several African states, invariably featuring a state-of-the-art sound system.

In 1976, singer Ntesa Dalienst joined TPOK Jazz, having been a mainstay of Orchestre Les Grand Maquisards for several years and, in 1978, Papa Noel was also recruited. Both were to make a major contribution to the Band’s continuing success.

But there was a setback in 1978, when Franco was arrested on grounds of obscenity in two songs, ‘Hélène’ and ‘Jackie’, which had been released surreptitiously. Franco is said to have defended his work but was undermined by his mother, who declared his compositions immoral.

He was jailed for six months and several of his musicians were also sentenced to two months’ imprisonment. The Un-Deux-Trois club was also closed.

However, Mobutu pardoned Franco and his musicians after they had been incarcerated for three weeks.

In 1979, perhaps shaken by this experience, Franco transferred his recording operation from Kinshasa to Brussels, moving there with his wife and children. He established a new record label there called Visa 80.

By 1980, much of TPOK Jazz had followed him into voluntary exile to escape the deteriorating economic and political situation in Zaire.

In January 1981, Franco released an album ‘Bina na ngai na respect’ on the French label SonoDisc, established in 1970 by former staff of Ngoma Records. The title track, written by Dalienst, was hugely successful.

Franco relocated Visa 80 to Paris, when TPOK Jazz were expelled from Belgium in 1982, because their passports didn’t permit them to work there. They returned to Zaire, where rumours had spread that their expulsion was linked to drug trafficking.

Shortly afterwards, Sam Mangwana returned briefly, recording the ‘Cooperation’ album with Franco. This received extensive airplay across Europe.

In 1983, Madilu System finally broke into the front rank of TPOK Jazz vocalists with his performance on the track ‘Non’, as recalled in the first episode of this series.

Later that year, TPOK Jazz toured in the United States for the first time with a 17-piece band, plus a dozen or so dancers and percussionists. In spring 1984 they featured at London’s Hammersmith Palais, Madilu leading the vocal section.

And it was in the autumn of 1984 that Franco and TPOK Jazz released the three-track album ‘Tres Impoli’, also featuring ‘Tu Vois’ (better known as ‘Mamou’) and ‘Temps Mort’.

Tres Impoli

The album was released in Brussels on the Edipop label, another Franco production and distribution vehicle. ‘Tres Impoli’ was numbered POP28 for European distribution. On this album, the song is unified.

But, confusingly, the same album was released in the United States, on the Makossa label, under the alternative title ‘Sorcerer of the Guitar’ and there was also another Edipop release in Kenya, POP20, which has the song divided into two parts, both on Side One.

There are various mixes available, not always of the best quality. My personal favourite is the unified, long version, lasting almost seventeen minutes, on Sonodisc’s ‘Franco et son TPOK Jazz: 3eme Anniversaire De La Mort Du Grand Maitre Yorgho’ (1993). That’s the one I’ve featured here.

The structure of the song is fairly straightforward. The assembled vocalists harmonise the short chorus, initially to at the opening of the song and then repeating it as a refrain at the end of each subsequent verse.

‘Ozalaka nayo tres impoli ehhh.

Ozalaka nayo tres impoli ehhh.

Ozalaka nayo tres impoli ehhh, ponini oh?’

This mixture of Lingala and French translates as:

‘You are always very rude.

You are always very rude.

You are always very rude, but why?’

The verses are half sung, half narrated by Franco himself and, within them, he files a long list of complaints about the rude behaviour of the unidentified individual he is addressing.

This is clearly the kind of behaviour that would have upset Franco and his contemporaries in 1980s Kinshasa.

The person described is definitely a man. He is rude and insensitive, having no regard for the niceties of etiquette. He also has poor personal hygiene and is a bit of a sponger.

I’ve edited the lyrics slightly in this translation so that they run more smoothly in English:

‘Why do you behave like that?

You speak without thinking.

You speak without consideration.

Why are you so shameless?

You enter people’s homes without knocking.

You walk straight into their bedrooms.

You talk to people without brushing your teeth.

Why are you so ill-bred?

You enter their offices without removing your hat

You have a lighted cigarette even when you know they don’t smoke.

You use the empty packet as an ashtray.

You enter their offices and read their private papers.

You arrive at their homes without having combed your hair.

Only to ask your host for a comb.

When your childhood friend has grown powerful

You will beg money from him during a ceremony.

You enter people’s homes and remove your shoes,

Although your socks have holes and your feet smell.

You enter their homes and stick your feet on the table

When people use that table to eat.

Having spent the evening somewhere,

You arrive at a friend’s house and raid his fridge.

But your friend has to live on a budget.

Don’t you know how expensive food is now?

You will eat his food until 2AM.

You enter homes and remove your shirt

But your underarms are sweaty;

You even try to raise your arms.

A friend lends you his mason’s trowel.

You use it for building, yet still you insult him.

Why do you behave like that?

You speak without thinking

You speak without consideration.

Why are you so shameless?’

Madilu is definitely in the mix on the chorus, but there are three or four other male voices that are not so easily identified. Some sources suggest Sam Mangwana is among them. I guess at Dalienst and Josky as two more.

They elongate the note that ends each of the first two lines of the chorus: ‘ehhh-ehhh’, which really emphasises the power and skill of their harmonising.

Musically, the horns begin the track, supplying a very brief introductory passage before the opening chorus.

Then we launch straight into the verses, delivered by Franco in his forceful, resonant but occasionally slightly hoarse voice, pitched lower than the chorus.

The horns add a four note coda after each line he sings: ‘barp-barp-be-ba’.

Behind him, but fairly low in the mix, we can hear percussion and a complex interplay of guitars weaving an intricate pattern that continues throughout.

From time to time Franco signals the end of his verse with his trademark ‘Mmmmm’, signalling that he has finished singing and it’s time for the chorus to launch in.

The sebene is midway through the song, between two iterations of the lyrics. For Franco, it is surprisingly lyrical. (Compare it, for example, with the insistent metallic twang on ‘Azda’) In my humble opinion it is even more powerful.

I suspect that may be because Franco is playing the lead on the mi-solo guitar, but I stand to be corrected. It picks up the melody that has been simmering away at the back of the mix all the way through.

The rhythm, lead and mi-solo guitars wind their magical skeins, the lead adding only relatively spare notes of emphasis.

Then the horns enter over the top for a while with a refrain that mimics the chorus, complete with those ‘ehhh-ehhh’ sounds. The horns are often a comparatively unnoticed dimension of Franco’s sound. Used sparingly, as here, they still make a powerful contribution to the overall effect.

Indeed, this is the point of sheer perfection in this track, as invariably demonstrated by those unruly hairs on the nape of my neck.

Then the guitars take over once more, before the second round of singing begins.

During the second set of lyrics, we can occasionally hear the voices of the chorus passing comment on what Franco is singing.

After they have sung the closing chorus, the guitars make their third appearance, the horns once again joining in with their refrain, and finally the guitars take the music to fadeout.

As far as I’m concerned, soukous doesn’t get any better than this.

I love ‘Ya Jean’ and ‘Cantique’, closely followed by ‘Marie Jose’, ‘L’argent Apelle L’argent’ and many, many more.

But I keep on returning to Franco, even though he played his last over 35 years ago. He still sounds fresh. I’m always bowled over by his unparalleled virtuosity, as an innovative and versatile guitarist, but also as a composer, arranger and social commentator.

‘Tres Impoli’ captures him at the very peak of his powers. If I ever had a desert island, this would be an indispensable accompaniment to my solitude.

TD

December 2025

Leave a comment