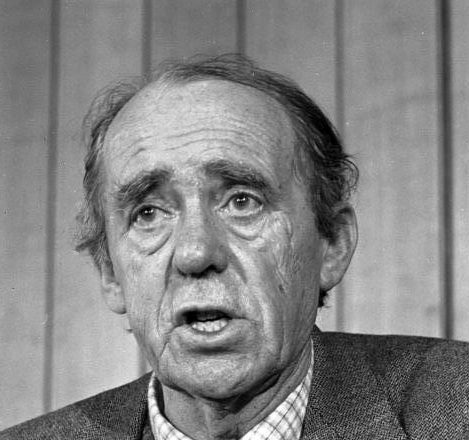

Heinrich Böll (1917-85) was born into a Roman Catholic, pacifist family in Cologne, Germany. He was conscripted in 1939, shortly after beginning a degree in German and Philology at the University of Cologne.

He served for five years in several countries and was four times wounded. On leaving hospital in August 1944, he tried to avoid further service by feigning sickness and using forged papers, but joined up again in March 1945 and was taken prisoner in April by advancing Americans.

In 1942 he married Annemarie Cech, a friend of his sister’s, and they went on to have four sons, though the eldest died shortly after the War ended.

Returning to Cologne, Böll worked for a while in the City’s statistical bureau, while beginning to publish short stories and, in 1949, his first novel.

Böll received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1972.

‘Billiards at Half Past Nine’ (‘Billard um Halb Zehn’) was published in 1959. I read the English translation by Patrick Bowles, published in 1961.

The novel deals with the events of a single day – 6 September 1958 – but employs a host of flashbacks to explore the history of three generations of the Faehmel family.

Heinrich is celebrating his 80th birthday on this very day. His son Robert, a creature of habit, plays billiards daily in a local hotel, always between 09:30 and 11:00. Robert’s son, Joseph, like Robert and Heinrich before him, is an architect.

Heinrich’s wife, Johanna, was placed in a sanatorium during the War, possibly because of her interest in helping the Jews. Robert’s wife, Edith, died in the War, possibly as a result of bombing. Joseph is seeing Marianne, who miraculously managed to escape her family’s suicide pact at the War’s end.

Schrella, an old school friend of Robert’s, returns to Germany after a long absence in the Netherlands and elsewhere. Both Robert and he had to flee Germany to escape the brutality of the Nazi police, having refused to take what Böll calls ‘the Buffalo Sacrament’ (by which he means giving support to the Nazis, and others wedded to physical violence).

Schrella meets some ghosts from his past, especially the former Nazi, Nettlinger, who persecuted them both during the War.

Heinrich is celebrated for having built the local Abbey of St Anton, but Robert, eventually recruited into the German army as a demolition expert, blows it up in the final days of the War, following the orders of an insane General who is obsessed with ‘the line of fire’. Robert is unhappy that the monks have supported the Nazis.

The War now over, Joseph is the architect working on the Abbey’s renovation. He discovers his father’s role in its destruction by finding his tell-tale markings on the ruins

As the family makes its way to Heinrich’s 80th Birthday Party, Joanna leaves her sanatorium, also determined to attend. She is armed with a pistol hidden in her handbag, but exactly who is she planning to shoot?

Finally, as the novel ends, Heinrich is presented with a birthday cake in the shape of St Anton’s. He cuts off the spire and passes it on a plate to Robert.

The novel is a complex puzzle, constructed out of the first person narratives of several of the leading characters, who naturally have rather different perspectives on other people and events. This makes it extremely difficult to follow the finer details of the plot, without constantly re-reading material from earlier chapters.

Nevertheless, the novel rewards the persistent, standing as powerful, thoughtful and evocative testimony to life in Germany during the first half of last century.

TD

June 2025

Leave a comment