This is the fourth in a series of twelve monthly posts, each exploring a musical composition of profound personal significance.

Each choice is connected in some way with its immediate predecessor, although these links may be tenuous because I am inventing them as I go along.

I began with Ya Jean by Madilu System – and will hopefully end with that, too, once the cycle of twelve is complete.

Madilu led me to Autorail by Orchestre Baobab and that, in turn, took me to Sweet Fanta Diallo by Alpha Blondy.

Thus far, then, we have visited the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Senegal and Ivory Coast. Next, we head to the United States of America for a slice of classic Southern Rock.

Indeed, it is thought the term was first applied to this month’s subjects, in a review of a gig they played in 1972. The author was an Atlanta journalist on an underground paper called The Great Speckled Hen. He rejoiced in the name Mo Slotin.

In February of that year President Nixon was about to visit China and the Watergate Conspiracy was already under way.

Several thousand miles away in England, a miners’ strike caused a national state of emergency and David Bowie’s alter ego Ziggy Stardust made his first appearance.

I was on the verge of my 13th Birthday, halfway through what is now called Year 8 at a Home Counties boys’ grammar school.

A shy, myopic, slightly-built youth, crowned with an unruly mop of ginger hair, struggling to control the powerful surge of testosterone.

On 12 February 1972, the Allman Brothers Band released their fourth album, Eat a Peach, on Capricorn Records.

The front cover depicted an oversized peach lying in the back of an elongated flatbed truck, set against a backdrop of scudding white clouds in a vivid blue sky.

It was a double album containing a mix of live and studio recordings. The former were drawn from several performances at New York’s Fillmore East the previous year. The latter were mostly recorded at Criteria Studios, Miami, between September and December 1971.

One of the studio tracks is Blue Sky. It features two outstanding guitar solos by two superb guitarists. But, by the time Eat a Peach was released, one was already dead and buried.

How do I connect it with Sweet Fanta Diallo?

Perhaps most obviously because Blondy’s song features a rainbow – and rainbows invariably appear in the sky, often while the sky is turning blue!

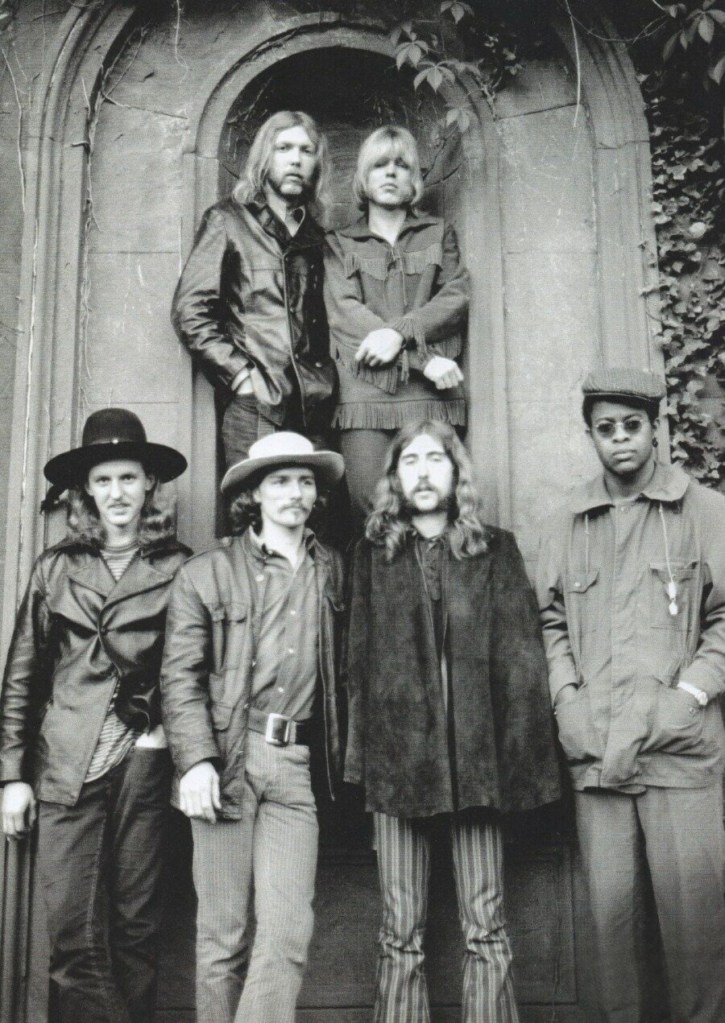

The Allman Brothers Band

Howard Duane Allman (better known as Duane) was born in Nashville on 20 November 1946; his brother Gregory Lenoir Allman (known as Gregg) on 8 December 1947.

Their father served in the army, but was murdered on Boxing Day 1949 when they were still toddlers. Their mother enrolled them both in a military academy, until the family moved to Florida in 1957.

Both boys learned to play guitar right-handed, though both were left-handed. By 1961 they had both started playing in local bands, Duane left high school early; Gregg graduated in 1965.

At that point they both went on the road with their own band, the Allman Joys, which subsequently became Hour Glass.

By 1968 Duane had become an outstanding session musician, working out of Muscle Shoals with the likes of Wilson Pickett, Percy Sledge and Aretha Franklin.

But he wanted to form a new band of his own, attracted by a novel formation built around twin lead guitarists and twin drummers.

By March 1969 he had the personnel he wanted. Aside from Duane and Gregg (who now played the organ and usually sang lead vocals) the band comprised:

- Forrest Richard Betts (Dickey) (1943-2024) on guitar;

- Raymond Berry Oakley III (Berry) (1948-1972) on bass;

- John Lee Johnson (Jaimoe) (b 1944) on drums and congas; and

- Claude Hudson Trucks (Butch) (1947-2017) on drums and percussion.

A second keyboard player – Reese Wynans – was dropped, presumably because Duane wanted only one of those (or else because Wynans was a threat to Gregg’s position).

The Allman Brothers Band gave their debut performance in Jacksonville, Florida but moved almost immediately to Macon, Georgia, to become the mainstay of new label Capricorn Records.

This drug-fueled, long-haired, mixed race ensemble enjoyed, at best, a strained relationship with many local residents.

Their first, eponymous album, The Allman Brothers Band, was released in November 1969; their second, Idlewild South, in September 1970.

Neither was commercially successful, though both contained what is now considered classic material, including Dreams and Whipping Post on the first; Midnight Rider and In Memory of Elizabeth Reed on the second.

Duane’s burgeoning reputation was further enhanced by the release of Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs in November 1970. By all accounts, he and Eric Clapton formed an instant bond, Clapton later referring to him as a ‘musical brother I’d never had but wished I did’.

But it was only with the July 1971 release of the live double album At Fillmore East that the Allman Brothers Band finally broke through to stardom. It perfectly encapsulated the controlled energy of their live performances, skin-tight and honed to perfection through their relentless touring schedule.

Many rock connoisseurs still rate it one of the best live albums ever recorded.

Only a few weeks after that release, the band returned to Criteria Studios in North Miami to work on three studio-based tracks for Eat a Peach: Stand Back, Little Martha and Blue Sky.

They had just played gigs on two successive nights, in Montreal and Miami respectively, and had only six days of studio time before their next concert in New Jersey.

They were, finally, on the cusp of wealth and fame. But, arguably, they had already reached their musical zenith. Much of the band was now addicted to heroin and it began to affect their performances.

Shortly after a Maryland gig on October 17, both Duane Allman and Berry Oakley flew to Buffalo to check into a rehabilitation clinic. But both checked out again within a week.

By October 28 Allman was back in Macon and, on the evening of Friday October 29, he was killed in a motorcycle accident.

At the inquest, the county coroner called it an ‘unfortunate accident’. Allman was travelling at speed along Hillcrest Avenue. A flatbed truck carrying a crane pulled out from Bartlett Street, directly in front of him.

Swerving to avoid the truck, Allman’s motorcycle skidded some way along the road with him pinned underneath. He was still alive on reaching hospital, dying three hours later of severe internal injuries.

He was a few weeks short of his 25th birthday – and a mere twelve years older than me.

This is the stuff of rock and roll legend, which thrives on prodigiously talented musicians who live too fast and die too young.

Just like Hendrix, Morrison, Joplin and so many others, Duane Allman’s stellar reputation has been further boosted by the tragic tale of his early demise. Over the years it has become progressively harder to separate the man from the myth.

The Duane Allman Myth survives intact, more than half a century after his death. Many refer to him reverently by his ‘Skydog’ nickname, even though it had limited currency while he was alive.

He was more often called ‘Dog’ (because of the undoubted physical resemblance) though, for some reason, Wilson Pickett called him ‘Skyman’. The two were subsequently combined.

It seems to me important to celebrate Blue Sky for itself, rather than as a monument to the memory of Duane Allman.

Moreover, the song’s reputation rests on the interplay between two powerful guitarists. Maybe Dickey Betts had the misfortune to die old. Perhaps he didn’t have quite the same genius, or acquire quite the same cachet, but his performances often came close to matching Allman’s, whether live or in the studio.

For those who like rankings, Rolling Stone’s 2023 countdown of the best ever guitarists (which I would describe, politely, as ‘idiosyncratic’ and advise you take with a huge pinch of salt), has Duane Allman at number 10 and Dickey Betts at number 145.

They are inevitably compared – and of course I shall compare them further below.

Dickey Betts

Forrest Richard Betts was born in a poor neighbourhood in West Palm Beach, Florida on 12 December 1943, some three years before Duane Allman.

It was a musical upbringing: his father, Howard, was a country fiddler; his mother played cornet in Salvation Army bands.

There were frequent family jam sessions, featuring what Betts later called ‘square dance music’. He could never master the fiddle himself, but began to play along at the age of five, learning ukulele before graduating to banjo, mandolin and, eventually, guitar.

Betts cited Chuck Berry’s Maybellene as one early influence, as well as Duane Eddy and Freddy King, conceding that, ultimately, he persevered with the guitar to attract more girls.

Around this time the family moved from Florida’s east coast to Sarasota, on the west, south of Tampa Bay. Betts joined a band called the Swinging Saints, leaving high school at 16 to play with them professionally on a nationwide tour, as part of a travelling circus.

He moved on to other forgotten Florida bands, with names like the Impossibles and the Jokers, occasionally picking up work as a club musician in Jacksonville:

‘We called it Jackass Flats: It was a redneck rough-ass town, a navy base where long hair wasn’t looked upon too good, especially late at night. I learned how to brawl in the streets and play the blues in Jacksonville.’

By the mid-60s he was fronting a band called Soul Children, playing covers in Sarasota clubs. Then Berry Oakley persuaded him to join his band, the Blues Messengers. They played more original material and held down a residency in a Tampa blues club.

In 1968 the Blues Messengers were poached to play in a new Jacksonville club, simultaneously changing their name to the Second Coming. Betts was now acquiring a reputation as one of the best guitarists in Florida.

Meanwhile, Duane Allman was trying to persuade Oakley to join the new band he was intent on forming. Allman played a series of jams with members of the Second Coming during which, by all accounts, Betts surrendered most of the solos to his younger rival. And Allman didn’t seem too grateful, appearing diffident and ‘standoffish’.

There was initially some mutual suspicion, but Oakley acted as intermediary, drawing them together. He was first to recognise how their playing styles complemented each other.

Betts later recalled:

‘Duane’s melody came more from jazz and urban blues, and my melodies came more from country blues with a strong element of string-music fiddle tunes. We were almost totally opposite except we both knew the importance of phrasing.’

‘[His] style was real definite, and mine was, too. We didn’t copy each other. We didn’t need each other. We were opposites. He had a stinging, spitfire trebly sound, and I had a B.B. King-Freddie King sound. I milk the notes longer. It was a real unique thing.’

Their long-time roadie, Joseph ‘Red Dog’ Campbell, added:

‘Duane played guitar better than anybody out there – except maybe Dickey Betts. Many nights Duane walked off stage and said to me, ‘goddamn, he ran me all over the stage tonight. He kicked my ass.’ It’s not that they were trying to outdo each other, but Dickey would come up with off-the-wall shit and Duane would have to keep up.’

Betts began to contribute his own compositions, notably the jazz-influenced instrumental In Memory of Elizabeth Reed on Idlewild South.

Later, after Allman’s death, he composed two of their best-loved tracks, Jessica and Ramblin’ Man, for the follow-up album, Brothers and Sisters (1973).

In between, he composed Blue Sky and sang the lyrics.

Even Bob Dylan has name-checked Betts, in Murder Most Foul (2020), though admittedly amongst a cast of thousands:

‘Play it for the Reverend, play it for the Pastor

Play it for the dog that got no master

Play Oscar Peterson, play Stan Getz

Play, ‘Blue Sky’, play Dickey Betts

Play Hot Pepper, Thelonious Monk

Charlie Parker and all that junk.’

It only fair that Allman should have the last word on Betts:

‘I’m the famous guitar player, but Dickey is the good one.’

Eat a Peach

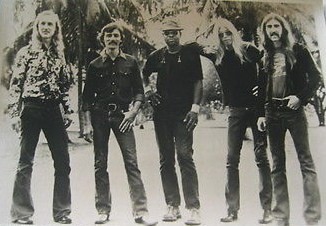

Following Allman’s death, the rest of the band discussed their future prospects, ultimately deciding to go back on the road. Two months later they were back in their Miami studio completing Eat a Peach.

With Gregg struggling in the wake of his sibling’s death, the older Betts gradually took on a more prominent leadership role.

They recorded three further post-Duane tracks for Eat a Peach: Melissa, ‘Ain’t Wasting Time No More and Les Brers in A Minor.

Ain’t Wasting Time encapsulates Gregg’s response to his brother’s death, while Les Brers is another Betts composition, the title allegedly a mangling of ‘less brothers’. (It should be ‘fewer brothers’ [Ed]).

They tried hard to make their music sound as good as it would have been had Duane still been around. They strove to get back in decent physical shape.

The album was still untitled when Duane Allman died, but the artwork had already been finalised. It was based on an old postcard though, for many years, an urban myth circulated to the effect that Duane was killed after crashing into a truck full of peaches.

The title was lifted from something Allman once said, when asked what he was doing ‘to help the revolution’:

‘I’m hitting a lick for peace—and every time I’m in Georgia, I eat a peach for peace.’

It has been suggested (by Butch Trucks, no less) that this is an indirect allusion to Prufrock:

‘Shall I part my hair behind? Do I dare to eat a peach?

I shall wear white flannel trousers, and walk upon the beach.

I have heard the mermaids singing, each to each.’

That seems a myth too far, even if Allman really was a fan of Eliot’s poetry.

It was more likely a ‘tongue in cheek’ reference to oral sex. Some sources indicate that Allman actually said something subtly different:

‘… Every time I’m in Georgia, I eat a peach for peace … the two-legged Georgia variety.’

The Album was released on 12 February 1972, eventually going gold and reaching number 4 on the Billboard Top 200 album chart.

The five surviving band members performed 90 gigs in the remainder of 1972, Betts taking over Allman’s slide guitar parts:

‘It was difficult to suddenly have to play slide. I’ve always enjoyed playing acoustic slide, but I never cared much for playing electric slide and I hated having to play Duane’s parts. It was uncomfortable, but if we were going to play those songs, then I had to play them.’

Even as Gregg Allman recovered his mojo, Oakley began to struggle in his place, overcome by the combined effects of depression, alcoholism and drug addiction. He began to be substituted.

Almost exactly a year after Duane Allman’s demise, he too died in a motorbike accident, crashing into a bus in much the same part of Macon.

But whereas Allman had everything left to live for, Oakley was a shell of his former self. He too was only 24.

They are buried alongside each other in Macon’s Rose Hill Cemetery

Blue Sky

Blue Sky is the fourth track on side three of Eat a Peach: five minutes and ten seconds of unadulterated pleasure.

Betts reportedly felt that Gregg Allman should take the vocals, but Duane encouraged Betts to do so, saying simply: ‘it sounds like you’.

Today the lyrics seem naive, hackneyed, anodyne even. They probably weren’t much better in 1972!

Betts begins with two verses of two lines apiece, followed by the four line chorus:

‘Walk along the river, sweet lullaby

They just keep on flowin’, they don’t worry ’bout where it’s goin’, no, no

Don’t fly, mister blue bird, I’m just walkin’ down the road

Early morning sunshine, tell me all I need to know, oh

You’re my blue sky, you’re my sunny day

Lord, you know it makes me high

When you turn your love my way

Turn your love my way, yeah.’

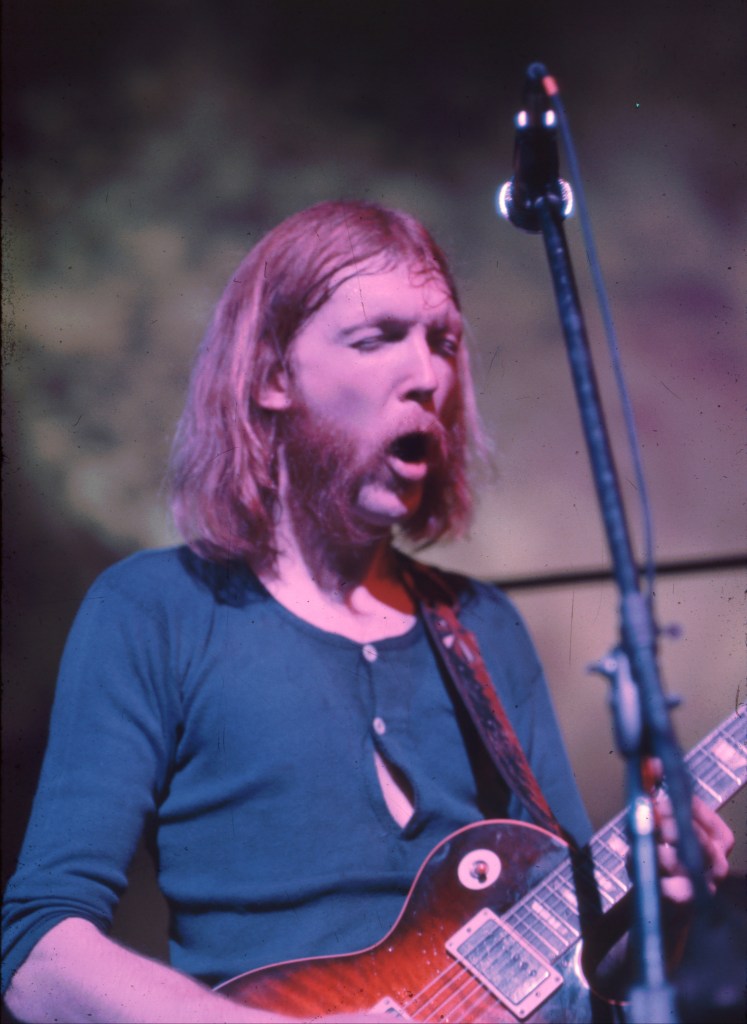

Allman’s guitar solo begins at 1:07 and then, after a brief shared section, Betts begins his solo at 2:37.

At 3:50 they share a melody together before Betts completes the song, adding one further verse and repeating the chorus for good measure:

‘Good old Sunday mornin’, bells are ringin’ everywhere

Goin’ to Carolina, it won’t be long and I’ll be there

You’re my blue sky, you’re my sunny day

Lord, you know it makes me high

When you turn your love my way

You turn your love my way, yeah, yeah.’

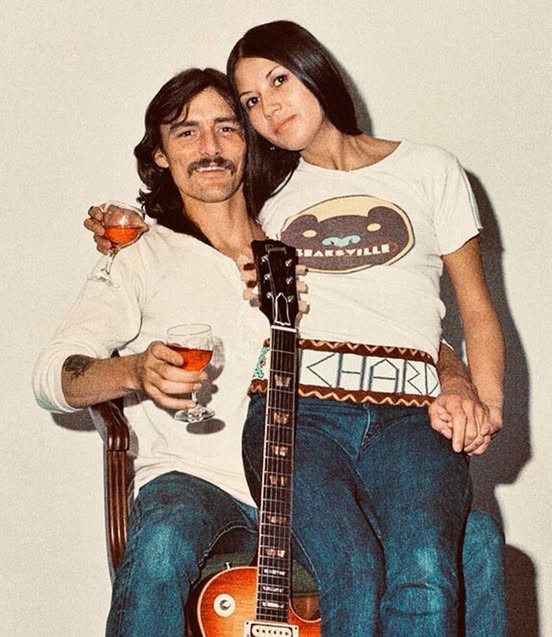

Betts wrote the song about his girlfriend, Sandy Wabegijig, but decided to remove any personalisation to make the song more relatable. Wabegijig was from a Canadian First Nations family, her surname, translated, means ‘clear blue sky’.

The song was written in the spring of 1971, when they had just begun living together in Love Valley, North Carolina. They had a daughter, Jessica, born in May 1972, (the inspiration behind the song of that name) and married in 1973.

They divorced in 1975, Betts apparently refusing to sing Blue Sky for a while afterwards.

But it would be quite wrong to assume Wabegijig was the love of his life. He had been married twice before he married her – and there were to be two more wives before he was through.

These lyrics were never going to rival Dylan’s. And Betts wasn’t a particularly strong singer either. His voice is thin, rather high-pitched, slightly nasal. The vocal track seems slightly subdued, perhaps a touch too low in the mix.

At best, he conjures up a laid-back, relaxed, slightly lilting groove as a foundation on which the track can build. But this is the classic ‘slow burn’, for the lyrics are merely the bread in this sandwich: the filling comprising the two chunky guitar solos, one after the other. Allman goes first.

At first listen, the two solos are strikingly similar, but subtle differences gradually reveal themselves.

Allman’s style is fuller, more rounded, bluesy and emotional. He builds sonorous phrases, one on top of the other, his guitar quite literally singing.

Betts seems to pick out the notes a little more carefully, slightly more staccato, country-style but also with a slight jazz inflection. He combines this succession of notes into beautiful melodic refrains.

It is instructive to listen to each in splendid isolation.

Here is Duane Allman:

And here is Dickey Betts:

Musical tastes differ but, heard like this, I’d guess the vast majority of musically educated listeners would give Duane Allman the edge, at this comparatively early stage in Betts’ career.

Betts is outstanding, but Allman is even better.

Curiously though, that edge seems to disappear when the two halves are placed together. The second half of Blue Sky is not noticeably different in quality to the first.

Maybe the whole is greater than the sum of the parts.

Or perhaps Duane Allman’s superb rhythm guitar work underpins Dickey’s lead so beautifully that it creates a combined effect equally as powerful, Duane’s solo needing correspondingly less support from Betts?

Johnny Sandlin was called in to finish the mixing for Eat a Peach. He recalled:

‘As I mixed songs like ‘Blue Sky’, I knew, of course, that I was listening to the last things that Duane ever played and there was just such a mix of beauty and sadness, knowing there’s not going to be any more from him’.

Does the sadness cling because of what happened to Allman, or is there anyway a slight air of melancholy about Blue Sky?

After all, skies are only temporarily blue, Sunday mornings will soon become Monday mornings and many more young men will die in motorcycle accidents…So it goes.

Personal relevance

I first encountered the Allman Brothers in 1974 when I was 15 years old. Tuning in to Radio Caroline, I particularly enjoyed the programmes dedicated to listeners’ favourite album tracks.

Some were almost ubiquitous: either Stairway to Heaven or Whole Lotta Love; either Time or Money; either Supper’s Ready or The Firth of Fifth; And You And I; Sympathy for the Devil; Radar Love.

Others were selected more sparingly, amongst them Jessica and Rambling Man.

Caroline rarely ventured into the Allmans’ back catalogue. I had to discover that for myself, initially buying their first compilation album, The Road Goes on Forever, when it was released in 1975.

I soon filled in the gaps by purchasing At Fillmore East and Eat a Peach too.

I distinctly recall giving a school assembly, most probably in 1976, on the theme of dreams and dreaming. I used the relevant Allman Brothers track to introduce my theme.

It simply wasn’t possible for a repressed English grammar school boy to take on the full Southern Rock shtick, but I mimicked some aspects, blending them with other musical influences, from funk and disco at one extreme to Frank Zappa and Caravan at the other.

This eclectic mix was further complicated by exposure to the bands I saw in this pre-punk era, amongst them: Dr Feelgood, Thin Lizzy, Cockney Rebel, Ace, Judas Priest, Groundhogs, Argent, Babe Ruth and Curved Air.

Blue Sky struck a particular chord. During my teenage years, I rated it the best guitar playing I’d ever heard. It’s still the best American guitar playing I’ve ever heard, but since then I’ve heard so much more, not least Syran M’Benza and Barthelemy Attisso.

Blue Sky still makes me joyfully happy-sad, the melancholic undertone forever associated with teenage angst.

Thankfully adolescence is a once in a lifetime experience.

TD

April 2025

Leave a comment