We returned to the Coast Path at the end of March 2025, some nine months after completing the section from Exmouth to Charmouth.

We based ourselves in Weymouth for a week, from Saturday to Saturday, reserving 5 Park Mews via cottages.com. This first floor, one-bedroomed holiday let cost £345 plus a £75 refundable security deposit.

Though smaller than the cottages we prefer, it was perfectly located, in the centre of town, just a few minutes’ walk from the bus stops and railway station. It had everything we needed, including a bath to soothe our aching limbs.

We had anticipated a straightforward journey to Weymouth, via the direct service from Woking, but hadn’t counted on weekend engineering works.

Our outward journey included a replacement bus service between Bournemouth and Poole, after which we could complete the journey by rail. There was a similar but slightly different arrangement on the return journey.

The weather was excellent throughout the week, mostly sunny, bright and warm, but also frequently windy. The only rainfall was on Thursday afternoon, after we had finished for the day.

The bus connections westwards from Weymouth were excellent and, though services were infrequent, they were always reliable. Single journeys now cost £3 apiece, but my new Freedom Pass made all but my early morning journeys free.

Our walking schedule turned out as follows:

- Sunday: Charmouth to Burton Beach (8.0 miles)

- Monday: Burton Beach to Abbotsbury (8.4 miles)

- Tuesday: Abbotsbury to Ferrybridge (10.9 miles)

- Wednesday: Rest day

- Thursday: Ferrybridge to Ferrybridge (Portland circular) (13.0 miles)

- Friday: Ferrybridge to Osmington Mills (8.3 miles)

That amounts to 48.6 miles, so we have now completed 595 miles of the Coast Path, leaving only 35 miles outstanding.

Weymouth

Weymouth is a substantial town of more than 50,000 people, the third largest settlement in Dorset. It sits on the eastern side of a promontory that culminates in the Isle of Portland, at the mouth the River Wey, a short chalk stream.

The Town developed out of two separate parishes located on either side of a harbour.

To the south lay Wyke Regis, which incorporated an area called ‘Weymouth’. It became a chartered borough in 1252, engaged principally in the wine trade.

To the north was Melcombe Regis, which emerged as a port in its own right, primarily supporting the wool trade. Some historians think it probable that the Black Death entered England in 1348 by means of a ship travelling from Calais to Melcombe Regis.

Queen Elizabeth brought the two parishes together as the double borough of Weymouth and Melcombe Regis in 1571. Shortly before this, Henry VIII had built two fortifications nearby, at Sandsfoot Castle and Portland Castle respectively.

In 1635, a hundred or so emigrants left aboard a ship called Charity, ultimately establishing the parallel settlement of Weymouth, Massachusetts.

The English version changed hands more than once during the ensuing English Civil War. Hundreds were killed in the Battles of Weymouth that took place in 1645.

Between 1789 and 1805, King George III devoted more than a dozen summer holidays to Weymouth. As a result the King’s Statue was erected in 1809, now enjoying pride of place on the seafront.

At roughly the same time, the Napoleonic Wars gave Weymouth increasing military significance. Portland Harbour was constructed for the Royal Navy between 1849 and 1872, with Nothe Forte standing at its entrance.

When Weymouth Station opened in 1857, tourism gathered pace. Up to 1987, the line extended, via Weymouth Harbour Tramway, to ferries serving the Channel Islands and Cherbourg. The last ferry service closed in 2015.

During the First World War, Weymouth became a major centre for the recovery and recuperation of injured servicemen, especially soldiers from ANZAC regiments. It was a regular Luftwaffe target during the Second World War, playing a significant role in the Normandy Landings.

Thomas Hardy (1840-1928) was a frequent visitor, featuring Weymouth in several novels, including ‘The Trumpet-Major’ (1880), in which he disguised it as ‘Budmouth’. John Cowper-Powys (1872-1963) published his novel ‘Weymouth Sands’ in 1934.

Thomas Love Peacock (1785-1866) was born here, while G A Henty (1832-1902) died aboard his yacht in the harbour.

More recent luminaries include comedians Alan Carr and Andy Parsons.

In October 2024 the Office for National Statistics recorded 49 pubs in Weymouth, equivalent to 87.86 pubs per 100,000 people. Some sources claim there were up to 90 pubs here in the 1960s.

It has the atmosphere of a pub-heavy locale, with a heavy drinking culture and some evidence of alcoholism, though that is often the case in larger English coastal towns.

Weymouth is certainly lively and seems relatively prosperous. There has been extensive regeneration over the last 20 years. We noticed relatively few empty retail outlets or permanent closures, though several eateries had not yet opened for the summer season.

I liked the Town’s buzzy vibe, its avoidance of sleepiness, but I couldn’t discern a unique personality: Weymouth’s charms are broadly generic.

Having arrived a little early to access our apartment, we pulled our suitcases along the Esplanade, stopping at a beach kiosk for coffee and pastries. One or two brave souls were bathing, but most other beachgoers were walking their dogs.

After unpacking we visited Tesco Extra for supplies, then embarked on a late afternoon orientation walk around the harbour. A crow half-heartedly attacked my head.

Afterwards we ventured back along the Esplanade to the Black Dog, calling in for a drink before picking up our customary fish supper. This one was supplied by King Edwards Fish & Chips.

Day 1: Charmouth to Burton Beach

We were up early for the 08:42 X53 Jurassic Coaster bus, departing from the seafront stop beside the King’s Statue.

The journey to Charmouth via Bridport takes some 90 minutes, including some slow ascents and sudden descents. We nabbed the front seats on the top deck for the full fairground-ride experience.

Alongside us, two women chattered excitedly: they were walking from Lyme Regis to Charmouth.

Having arrived at Charmouth beach, we bought coffees from the Soft Rock Café. My initial preference for the nearby Beach Café was overruled by Tracy, because we had previously bought ice creams there.

She calls this principle ‘varietousness’.

The coffee was mediocre but, who knows, it could have been even worse at the Beach Café.

It was a beautifully fresh, sunny morning as we began our ascent behind the beach, heading in the direction of Stonebarrow Hill, above the cliff face known as Cain’s Folly (derivation uncertain).

We passed through this ornate field gate, part of the West Dorset Walkers Welcome project, commemorating the landfall of Danish Viking ships on Charmouth Beach in 836.

The Anglo Saxon Chronicle places this three years beforehand:

‘This year fought King Egbert with thirty-five pirates at Charmouth, where a great slaughter was made, and the Danes remained masters of the field. Two bishops, Hereferth and Wigen, and two aldermen, Dudda and Osmod, died the same year.’

Soon afterwards we reached the first of many clumps of vivid yellow broom.

We were now in the National Trust’s Golden Cap Estate, named after the massive flat-topped hill rearing ahead. It reaches a height of 191m (627 feet) and is said to be the highest spot on England’s south coast.

The golden shade on the higher reaches is attributable to Upper Greensand, a variety of sandstone, weathered for 100 million years or so.

The climb is not quite as stiff as it appears. On the summit there is a small stone memorial commemorating Randall McDonnell, 8th Earl of Antrim, who chaired the National Trust from 1966 to 1977.

Soon afterwards this unusually shaped tree root, shaped like an arthritic hand, is another WDWW production (and by no means the last).

Looking back on this side, the striking colour of Golden Cap is more visible.

Somewhere on the descent we spotted an elderly couple climbing towards us. Mindful of coast path protocol, I gave way, stopping to allow the woman to pass by.

But, in momentary hesitation, she couldn’t decide whether to lead with her arthritic knee or her artificial hip (as she afterwards explained) and promptly took a tumble. Fortunately she was fine; her male partner’s equanimity undisturbed meanwhile.

Reaching Seatown we stopped for lunch at a picnic bench just in front of the Golden Cap Holiday Park. We were greeted by strains of impromptu guitar music, played by someone near the Park’s entrance.

There is little else at Seatown, other than the Anchor Inn and some public toilets, neither of which we patronised.

An earlier iteration of the Anchor was destroyed by the Great Storm of November 1824, of which more below. It also caused extensive damage in Weymouth, where boats were said to have been washed through the streets.

We continued on our way, completing the stiff climb out of Seatown towards Thorncombe Beacon. There are three Bronze Age bowl barrows nearby.

We admired a wooden triptych, from WDWW of course, recalling the smuggling that was once endemic here.

It quotes from ‘A Smuggler’s Song’ (1906) by Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936):

‘Five and twenty ponies,

Trotting through the dark –

Brandy for the Parson, ‘Baccy for the Clerk.

Laces for a lady; letters for a spy,

Watch the wall my darling while the Gentlemen go by!’

We could see the length of Eype Beach stretching towards West Bay, far below. The village of Eype stands back from the Beach, its name derived from the Old English for ‘steep place’.

St Peter’s Church also functions as Eype Centre for the Arts, where PJ Harvey recorded much of her album ‘Let England Shake’ in 2011.

Passing Eype Beach Holiday Park, I admired a row of three ‘glamping pods’ that resemble a military installation. We climbed past an upturned rowing boat and a brick-built pill-box, soon finding many more pods at Highlands End Holiday Park.

A notice explains that a nearby site is used by the ‘Devon & Somerset Condors Paragliding Club’.

It adds, quite unnecessarily:

‘Paragliding can be a dangerous activity.

Participating pilots do so at their own risk.’

Soon we had reached the outskirts of West Bay. The beach was fairly quiet, but the quayside round the harbour was heaving. A traffic jam of day trippers dawdled slowly round the margin while a bunch of men in wellington boots and waders dug about purposefully in the harbour mud below.

West Bay is essentially Bridport’s harbour, formerly used to export ropes and nets manufactured there. The original location was further inland, but prone to silting and ultimately too small, so this one was constructed in 1740.

The advent of steam power hastened its decline. The railway reached Bridport in 1857 and was extended to West Bay by 1884, but that extension had closed to passengers by 1930.

West Bay is now forever associated with the television series ‘Broadchurch’, but was also used as a location for the film version of ‘The Navy Lark’ (1960).

It took a quarter of an hour to ease our way through the holidaymakers. Finally escaping into fields, we immediately encountered a diversion caused by a landslip on the seaward side of the Bridport and West Dorset Golf Club.

I’m not too keen on massed holidaymakers, but regular readers will know that I’m even less enthused by golfers and their golf courses – just one of many unjust prejudices, I fear.

A partly-fenced path had been created between the fairways, which led us eventually into Freshwater Beach Holiday Park. The signage here left much to be desired. It was only with some difficulty that we worked out where to cross the River Bride, before doubling back on ourselves to regain the coast once more.

We passed beneath the village of Burton Bradstock, whose name recalls its location on the Bride, but also that it was once owned by Bradenstoke Priory, some 80 miles distant.

Eventually we reached Burton Beach, also known as Hive Beach, my target for the day, where we joined a lengthy queue at the Hive Beach Café.

The Whippy machine had already been emptied but, mercifully, came back into operation as we reached the service hatch.

We took our purchases down to some benches just behind the beach, watching several small children enjoying themselves. One particularly adventurous baby had launched a daring escape bid.

Billy Bragg may or may not live in a mansion just round the corner, beyond the National Coastwatch lookout. Some newspaper reports say he sold up in 2021, but other sources are less sure.

Walking up Beach Road to Common Lane, we arrived at the bus stop well before the X53 back to Weymouth.

We found the two ladies from that morning – and an amiable but voluble drunk besides. He hit trouble when declaring that he’d like to shag a specific someone’s daughter…There were groans and sharp intakes of breath.

He apologised profusely to all his listeners and peace descended once more.

Dinner was at home that evening. While half-watching the television I replied to a woman who had engaged me on social media about Dracup family history.

A former Dracup herself, she grew oddly suspicious, apparently egged on by another family member, formerly a policeman.

Our correspondence culminated in her declaring me ‘a f***ing scammer’.

Sadly, possession of the Dracup surname doesn’t guarantee a strong intellect: some will always tend towards a thickness substantially greater than two short planks.

Day 2: Burton Beach to Abbotsbury

We caught the same X53 departure from the same stop, except that it departed ten minutes earlier on a weekday. A pony was being exercised upon the beach, as joggers puffed their way along the Esplanade. The weather remained bright and sunny, but the breeze was noticeably cooler.

The two ladies from yesterday climbed aboard at the Station, hastily finishing their breakfasts.

We reached Hive Beach by 09:30, now almost deserted, some half an hour before the Café would reopen. The man from the National Coastwatch lookout, in hi-viz jacket, scrutinised the small waves lapping on the beach before returning to his post.

Expecting limited coffee-drinking facilities, we had filled our flasks, enjoying a quick slurp while sitting on the same benches as the evening before. (For whatever reason, ‘varietousness’ did not apply.)

We both needed a comfort break rather urgently, but having reminded Tracy of the ‘beware of adders’ signage, we both agreed to hold on for a while!

Climbing up beside the dunes we soon reached the Old Coastguard Holiday Park, several dog walkers forcing us to hold fire meanwhile. We eventually found relief in a narrow cleft on Cogden Beach, from where one could see the full stretch of Chesil Beach, all the way round to Portland.

We admired a small cairn sheltering near a concrete ruin and, slightly later, a stone circle. The Coast Path turns slightly inland here, passing to the landward side of Burton and Bexington Meres, with their surrounding reed beds, a haven for birdlife.

A rabbit munched on the grass ahead, failing to notice us until we were almost on top of him.

As we approached West Bexington the path round the field edge was flooded, so there was no choice but to take to the beach. The official guide refers to a ‘covered walkway’, but that must be a figment of the author’s imagination for the Dorset Wildlife Trust says there are no surfaced paths.

It took us a while to cross the half mile or so of beach before West Bexington, essentially a car park from which two rows of houses stretch inland. The Café was closed.

We rested while trying to establish how far the path continued along the Beach towards East Bexington, since the map shows a track called Burton Road. This materialised eventually and our progress became much smoother.

We reached a mysterious pile of rectangular stones, words inscribed around their sides, but couldn’t manage to work out their meaning. This turns out to be yet another WDWW artwork, naming some of the unusual plants that live here, including tassleweed, mouse ear and toothed medick.

A little further on there is a wooden bench commemorating John Varley, who lived in the Old Coastguards Cottages behind. It features John Masefield’s (1878-1967) Sea Fever (1902):

‘I must go down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky,

And all I ask is a tall ship and a star to steer her by;

And the wheel’s kick and the wind’s song and the white sail’s shaking,

And a grey mist on the sea’s face, and a grey dawn breaking.

I must go down to the seas again, for the call of the running tide

Is a wild call and a clear call that may not be denied;

And all I ask is a windy day with the white clouds flying,

And the flung spray and the blown spume, and the sea-gulls crying.

I must go down to the seas again, to the vagrant gypsy life,

To the gull’s way and the whale’s way where the wind’s like a whetted knife;

And all I ask is a merry yarn from a laughing fellow-rover,

And quiet sleep and a sweet dream when the long trick’s over’.

One of the Cottages, Mark Cottage, is presently for sale, priced at £800,000. This price includes The Rocket House, a beach house at the bottom of the garden.

We passed another pillbox on the hillside approaching Abbotsbury, alongside a brick-built platform with staircase, now empty. A small fishing boat lay just off shore.

Reaching the Abbotsbury car park at Buller’s Way, we were eagerly anticipating a pre-lunch coffee at the Chesil Beach Café. Although advertised as open, it too was closed.

So we climbed the wooden walkway on to Chesil Beach and had our lunch there, overlooking a pair of sea fishermen and a small blue tent, one end threatening to take off in the stiffening breeze.

Chesil Beach is officially 29 km (18 miles) long, stretching from West Bay to Portland. It reaches a maximum height of 15 metres and a maximum width of 200 metres.

It is made of shingle that varies in size from one end to the other. At the eastern end, pebbles may be up to 5cm long, whereas they are typically pea-sized near West Bay. Fishermen and smugglers were said to use this method to establish where they had landed.

Sailing vessels were particularly vulnerable to shipwreck on Chesil Beach during south-westerly gales, so several coastguard lookouts were posted along its length.

Making our way inland, we began to climb towards St Catherine’s Chapel, enjoying the picturesque view down towards the Swannery below.

We passed a sign for the Macmillan Way, a 290-mile path connecting Abbotsbury with Boston in Lincolnshire. And we appreciated this bench, dedicated to Daph, wondering what story lay behind the phrase ‘Never lose height’.

The Chapel was built in the late Fourteenth Century by the monks of Abbotsbury Abbey, below, as a place of pilgrimage and retreat. It is built out of local limestone.

English Heritage oversees the Chapel. According to it, St Catherine of Alexandria (she of the Catherine wheel):

‘…became the patron saint of virgins, particularly those in search of husbands, and it was the custom until the late 19th century for the young women of Abbotsbury to go to the chapel and invoke her aid. They would put a knee in one of the wishing holes in the south doorway, their hands in the other two holes, and make a wish.’

The Chapel featured briefly in Powell and Pressburger’s ‘The Small Back Room’ (1949).

Having taken our fill of photographs, we descended towards Abbotsbury, diverting slightly from the Coast Path to emerge on Chapel Lane.

Abbotsbury sits about one mile inland from Chesil Beach. Abbotsbury Castle is actually an Iron Age hill fort, located some seven miles distant from its more famous neighbour at Maiden Castle.

The first documentary evidence of Abbotsbury appears in a Tenth Century royal land charter. In the following century, Cnut granted more local land to one Orc who, settling in the area, founded the Benedictine monastery of Abbotsbury Abbey during Edward the Confessor’s reign.

The Abbey acquired considerable wealth and lands but, in subsequent centuries, it and the surrounding village were several times attacked from the sea, and the population was also much depleted by the Black Death.

Henry VIII closed the Abbey in 1539, granting the estate to Sir Giles Strangways, the commissioner who had conducted its dissolution. It passed through several generations to Stephen Fox, First Baron Ilchester (1704-76), via his wife, whose maternal grandmother was a Strangways.

Aside from the Abbey ruins there is a tithe barn, dating from around 1400, as well as the parish church of St Nicholas, originally Fourteenth Century. The Subtropical Gardens were founded by the Countess of Ilchester in 1765.

The Swannery may have been established as far back as the Eleventh Century, though the earliest written records are from 1393. It is thought to be the only surviving managed swannery in the world, its population numbering around 600 birds.

Abbotsbury saw one or two skirmishes during the English Civil War, Parliamentarians destroying the home of Royalist Colonel Strangways, a descendant of Sir Giles.

Several other buildings date from the Seventeenth or Eighteenth Centuries, when fishing was the dominant industry here. By 1861, the population was almost 1,100, but is today less than half that number.

Much of the Village is still owned by the Ilchester Estate. By some accident of inheritance it is the property of Hon Mrs Charlotte Townsend, daughter of the ninth Viscount Galway, estimated to be worth a cool £489 million.

By virtue of the Swannery, and excepting the King, she is the only person resident in this country permitted to own swans.

We ended our walk at Bellenie’s Bakehouse where we were kept amused by the owner’s quips while scoffing his delicious Dorset Apple Cake.

At some point in the conversation he decided that we must move to Bridport. Abbotsbury is too busy with tourists and traffic, he said, although the Neubergers have clearly decided otherwise.

We had time for a brief tour, taking in the remains of the Abbey, the churchyard and tithe barn. There are several ‘artisanal outlets’, studios and the like. We browsed through the Dansel Gallery, a huge collection of wooden products for sale.

We caught the X53 outside the Swan public house and, on the way into Weymouth were joined by pupils from Budmouth School who sat directly behind us:

Pupil 1: ‘That’s what I’m like; I say odd things at the wrong time’.

Pupil 2: ‘No shit!’

The two ladies were also aboard. Passing them on the street afterwards, we learned that they were heading home next day.

That evening we took advantage of a 25% discount at the Ship Inn beside the Harbour. I had a prawn cocktail starter, followed by steak pie with mash and red cabbage, finishing with New York cheesecake.

Day 3: Abbotsbury to Ferrybridge

Next morning we were back on board the 08:32 X53 for the final time, reaching Abbotsbury by around 09:00.

It was April Fools’ Day.

Tracy insisted that we make our way back to the precise point we had left the Coast Path on the previous day, before climbing up to the Chapel. Not being quite such a stickler in these matters, there was a fair bit of grumbling before I obeyed.

Having skirted the hill once more, we made our way round and down past the miller’s garden, crossing a stream before arriving beside the Swannery.

The first part of our route took us across country, to protect the bird colonies on the upper reaches of The Fleet – the body of water lying immediately behind Chesil Beach.

For much of the morning we made our way across a succession of fields, in near-perfect spring weather.

Before reaching Merry Hill we turned abruptly down the slope, following a stream through farmland slightly to the west of Langton Herring. A small herd of cows were an unwelcome obstacle just ahead of another pair of ornate gates, courtesy of WDWW.

There was still some waterlogging in this section, but we finally reached two benches immediately above The Fleet, one occupied by a pair of elderly twitchers with binoculars. They moved off soon after we arrived, so we took their bench and drank some coffee before resuming ourselves.

The Fleet is a large, shallow, brackish tidal lagoon, no more than five metres deep. It is 13 kilometres long, the width varying from 65 metres to 900 metres. It covers a total area of almost five hectares.

Aside from ducks, geese and swans, visitors may find the likes of wigeon, pochard and even an occasional osprey.

Several boathouses are built beside the shore, mostly on the Chesil Beach side. In some cases the surrounding area is kept relatively tidy; in others, far less so.

The wind grew stronger and more blustery as we progressed eastwards. A succession of walkers passed by, all heading in the opposite direction, and a helicopter flew overhead, glinting in the sunlight.

The path cuts across the neck of Herbury Island, a rounded promontory that juts into The Fleet.

An abortive effort was made to drain the entirety of The Fleet between 1630 and 1646. Then, from 1665, one William Fry tried to drain the area north of Herbury, which has subsequently become known as ‘Fry’s Works’.

The Great Storm of 1824 also caused havoc on The Fleet. A huge wave overtopped Chesil Beach, sweeping along the lagoon and carrying away buildings in its path.

To the south of Herbury, Gore Cove stretches round to Moonfleet Manor, a hotel that takes its name from the 1898 novel by John Meade Falkner.

The Manor was previously called Fleet House. Its Historic England listing says it is Eighteenth Century, with late Victorian remodelling and restoration. It may share the site of a predecessor built by Maximilian Mohun of Fleet (1596-1673).

The house subsequently passed to a family called Gould, who sold it on to a Bristol brewer called George. In 1946 it opened as Moonfleet Hotel.

Falkner’s novel is set in the 1750s, in a village called Moonfleet, after a once prominent local family, the ‘Mohunes’.

A plaque commemorating Falkner may be found in the Old Parish Church, further down the lagoon. It was badly damaged in the Great Storm, causing a new church, Holy Trinity, to be built slightly further inland. The Old Church still serves as a Mortuary Chapel for members of the Mohun family.

The village of Fleet stretches along the lagoon from Moonfleet Manor to East Fleet, some way beyond the Old Church, but very few properties are visible from the Coast Path, which sticks beside the shore.

We found a sheltered bench at the point where a footpath leads inland to the Old Church and stopped for our sandwiches. Four swans preened themselves just offshore.

Afterwards we pushed on past occasional circular concrete pillboxes and WWDW installations until the Tidmoor Firing Range near Chickerell.

The signage was alarming, but the firing range was thankfully silent.

Having skirted the large flat-topped mound, we found the substantial Haven Littlesea Holiday Park, and took advantage of a small copse just beyond for an afternoon coffee break.

Before long we were alongside another substantial MoD complex within a huge wire fence. This is the Wyke Regis camp, originally built by the Royal Engineers in 1928 to provide military training in the construction of bridges and ferries.

During the Second World War, the RAF conducted some of their ‘bouncing bomb’ trials here.

Having finally emerged from the vicinity of the wire, we could see Portland looming ahead but, rounding Pirates’ Cove, the Coast Path signage abruptly disappeared.

We started across the beach but gave up half way, only to meet a dog-walker who confirmed it was the correct route after all. However, the Path was closed further on, owing to a landslip near the Chesil Beach Holiday Park.

Having reached the point of closure, we began the official diversion, which directed us through suburban Wyke Regis. We stopped to speak with a couple coming from the other direction. They told us the landslip was impassable, even on the beach, owing to extensive mud.

We reached the bus stop on the A354 Portland Road shortly after 15:00. The school-run traffic was at its peak, so it took an age to reach Weymouth town centre.

Having finally reached our destination, we dropped into the Wafflicious ice cream parlour, taking our purchases over to a shelter on the Esplanade. We braved a mini-sandstorm while watching a helter-skelter being erected on the beach.

That evening we visited The Boot for a drink on a friend’s recommendation, finding it in the hands of new owners. Then we moved on to the Old Rooms for a dinner I’d booked a few hours previously.

We were worried since a group of 12 had arrived just ahead of us, but our food arrived on time and was really rather tasty. I had a king prawn, chorizo and feta starter, followed by pulled lamb shepherd’s pie with vegetables. Sadly though, the pub had only a single beer on draft – Greene King IPA.

Rest Day

After a late start we walked down to Pascal’s Brasserie on Cove Street where we met Sonia, Tracy’s former nursing colleague and a Weymouth resident, for an extended brunch. They hadn’t met for several years so a great deal of catching up was required.

In between, we both enjoyed superb full English breakfasts.

We began the afternoon with a visit to Books Afloat, an old-school second hand bookshop, cash-only and crammed to the rafters. It reminded me greatly of the late and much-lamented Scientific Anglian in Norwich.

Although it specialises in nautical titles, I confined myself to the classic literary paperbacks section, coming away with ‘Not Wisely But Too Well’ (1867) by Rhoda Broughton, ‘The Golovlevs’ (1880) by Mikhail Saltykov-Schedrin and ‘A Girl of the Limberlost’ (1909) by Gene Stratton-Porter. A good haul, all told.

After touring parts of the town centre we’d so far missed, we homed in on The Good Life Café Bistro where we had our compulsory cream tea.

The evening was spent indoors, quietly, and involved negligible eating!

Day 4: Ferrybridge to Ferrybridge (Portland Circular)

There had been much prior discussion and consultation over the question whether to take Portland in a clockwise or anti-clockwise direction.

The official guide favours clockwise (the east coast first) on the grounds that the best views are from the west side. However, since we are now walking the Coast Path in an easterly direction, anti-clockwise (the west coast first) is more logical.

Perhaps surprisingly, Tracy had no definitive ruling on the point, ultimately leaving it to me to decide. I opted for anti-clockwise, partly because the best of the weather was expected in the morning.

We caught a number 1 bus from the Esplanade, reaching Ferrybridge a few minutes before 09:00. We were buffeted by a stiff, cold breeze as we began the exposed stretch across to Portland, and there were a few drops of rain.

Portland is not really an island since Chesil Beach (as well as the A354) connect it to the mainland.

It took a while to reach comparative shelter. There is little on one’s starboard side, apart from the endless shingle, though the Dorset Wildlife Trust’s Wild Chesil Centre breaks the monotony early on, supplying welcome toilets.

On the port side there is, initially, a miscellany of boats and businesses. Amongst the most prominent is Billy Winters Bar and Diner, which apparently borrows the fishermen’s nickname for a small local prawn caught only in the winter months.

After a while the portside action gives out, only resuming with a large ‘drive thru’ Starbucks, near Hamm Roundabout, rapidly succeeded by an even larger Lidl.

There is a second roundabout, and then a third, preceded by two slim chimneys, carved out of Portland stone. They commemorate Portland’s six freemasons’ lodges: Portland, Loyal Manor, Quintus, United Service, Vindelis and Chesil.

That’s a lot of silly handshakes for such a small place: Portland is only six kilometres long and no more than 2.7 kilometres wide, with a population of some 13,000.

Incidentally, Vindelis (or Vindilis) was supposedly the Roman name for Portland.

Some centuries later, in 789 or thereabouts, there was another Viking raid in the vicinity. This is taken from Aethelweard’s Latin version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, produced around 980:

‘Suddenly a not very large fleet of the Danes arrived, speedy vessels to the number of three; that was their first arrival. At the report the king’s reeve, who was then in the town called Dorchester, leapt on his horse, sped to the harbour with a few men (for he thought they were merchants rather than marauders) and admonishing them in an authoritative manner, gave orders that they should be driven to the royal town. And he and his companions were killed by them on the spot. And the name of the reeve was Beaduheard.’

From 1140 onwards, there are several references to a castle, possibly built during the reign of William Rufus (1087-1100). It might have been on the site of the Rufus Castle ruins visible today (see below) but, then again, it might not.

We made our way to Chiswell Beach, at the extreme end of Chesil Beach, and the delightful Quiddles Café on the sea wall. The sun had emerged as we sat outside, on the pastel-coloured chairs, overlooking the deserted beach below.

Various streamers and balloons floated above us, possibly to discourage seagulls.

There was once a distinct village of Chiswell, previously called Chesilton, but the loss of 30 lives and 80 houses in the Great Storm marked the onset of its decline.

Ascending the slope behind, we initially lost our way, heading down towards a colony of huts. Eventually we found the right path, beside the basketball court, emerging on to the clifftop with a splendid view of Chesil Beach, stretching all the way back towards West Bay.

Inland we could see the Portland Cenotaph, first erected in 1926, which commemorates the 237 islanders lost in the First World War and the 108 killed in the Second. There is also a memorial nearby for the 13 men killed by an explosion aboard the submarine HMS Sidon in Portland Harbour in June 1955.

We entered Tout Park Quarry, now a sculpture park and nature reserve. The Quarry was active for two centuries, closing in 1982. The Portland Sculpture and Quarry Trust opened the sculpture park in 1983.

This is ‘The Roy Dog’, reputed to live in Cave Hole, on the south-east coast of Portland (see below). He is a black dog, large as a man, with fiery eyes, one coloured green, the other red. He is prone to seize unwitting passers-by, carrying them down into his dreadful lair.

Near the site of Blacknor Fort there is a small plaque commemorating ‘Barry Humphries of Cirencester’ (1978-2010). He crashed 65 feet to his death here one Saturday afternoon, when falling rocks severed his safety rope.

Blacknor Fort, completed in 1902, was subsequently equipped with two 9.2 inch guns. It was decommissioned in 1956 and, today, a private home sits on the gun emplacement’s concrete surround.

Passing the rather less attractive accommodation above Mutton Cove, we reached the western extremity of Southwell, where stands part of the former Admiralty Underwater Weapons Establishment (AUWE), a top secret installation during the Cold War.

It was targeted by what became known as the Portland Spy Ring, active between 1953 and 1961, which passed classified documents to the Russians.

We could now see the tops of several buildings on Portland Bill ahead, though had to wait for two horses to walk past before getting any closer.

The first to appear is the Old Higher Lighthouse, at Branscombe Hill.It was first constructed in 1716, together with its partner, the Old Lower Lighthouse on the eastern side of Portland Bill.

Both were rebuilt in 1869 then, once the present lighthouse was completed, the old ones were auctioned off.

In 1923, Marie Stopes bought Old Higher as a summer residence.

From beside the National Coastwatch lookout there is a clear view of the current Lighthouse itself, its stark red stripe vivid against the dim blue haze of sea and sky.

It stands 41 metres high, cost £13,000 to build and came into operation on 11 January 1906. The distinctive red foghorn was added in 1940. The Lighthouse is no longer manned: it was automated in 1996 and is now controlled from Harwich.

A white stone obelisk, seven metres high, stands further seaward. It was built in 1844 and is intended to warn mariners of a rock shelf jutting out below the waterline.

As the breeze stiffened, we chose a bench some distance beyond the lighthouse on which to eat our lunch.

While we munched, a small vessel rounded the Bill, fairly close to the shore. But this didn’t seem to provide the money shot for the assembled photographers, standing poised behind their tripods below Red Crane.

Such cranes were once used to load Portland Stone, but now solely by fishermen.

The photographers were still poised as we left, perhaps half an hour later. We navigated our way through a host of wooden beach huts, soon reaching the Broad Ope crane above Cave Hole. I hurried past without stopping, just in case the Roy Dog was lurking.

I did photograph wooden Sandholes Crane as we passed by.

We progressed through a series of abandoned quarries, eventually climbing up to the road near Cheyne House, overlooking Freshwater Bay.

What I took to be another wartime installation is a pumping station, formerly used to raise water from the bottom of the cliffs.

Heading along the Southwell Road, we missed the unmarked path down on our first attempt, enjoying a short rest on a handy bench before retracing our steps.

On the descent we met a young man walking towards us and passed the time of day. He planned to walk the entire Coast Path in one effort, following the 52-day itinerary but in reverse, camping out each night. He must have been half way through his first week.

I politely explained Tracy’s strong reservations about taking the Coast Path backwards. Only to discover her sympathetic to his excuse – that he would be returning to Bristol, and Minehead is far closer to Bristol than Poole.

He warned us of poor signage in the section he had just completed.

Soon we had entered the undercliff and were descending through the heavy undergrowth to secluded Church Ope Cove, where there is a further collection of residential beach huts.

Some believe this may be where Beaduheard was killed by Vikings in 789 AD.

A party of schoolchildren sat, mostly crosslegged, on the beach.

The picturesque ruins of Rufus Castle perch immediately above the Cove, this iteration dating from the Fifteenth Century. Richard, Duke of York, had it built between 1432 and 1460, possibly on the site of an earlier fortification (see above).

What survives is part of a keep, once a tower shaped like an irregular pentagon. The walls were up to seven feet thick.

JMW Turner drew these ruins in 1811, and they also feature in Hardy’s novel ‘The Well-Beloved’ (1897), under the name ‘Red King’s Castle’:

‘Eastward from the grounds the cliffs were rugged and the view of the opposite coast picturesque in the extreme. A little door from the lawn gave him immediate access to the rocks and shore on this side. Without the door was a dip-well of pure water, which possibly had supplied the inmates of the adjoining and now ruinous Red King’s castle at the time of its erection.’

The name of the Cove refers to St Andrew’s Church, whose last few remaining stones also sit above it. The official listing refers to Twelfth and Fourteenth Century elements, noting that it was abandoned in the Eighteenth Century.

Also nearby, but not quite visible from the Coast Path, is Pennsylvania Castle, a mock-Gothic mansion built in 1800 for John Penn (1760-1834), who later became Governor of Portland. It too appears in ‘The Well-Beloved’, as ‘Sylvania Castle’ and is now an upmarket hotel and wedding venue.

Marie Stopes, a close friend of Hardy’s, was a regular visitor to the Cove, reportedly scandalising the natives by indulging her passion for skinny-dipping.

A generation later, the Portland Spy Ring helped two Russian spies to land here.

The top of the climb out of Church Ope Cove is marked by a large stone ammonite dug into the earth. It commemorates the opening of the first section of the King Charles III England Coast Path in 2012. This runs the 20 miles from Rufus Castle to Lulworth Cove.

Such ‘doubling up’ may help to explain some of the dodgy signage, for the SWCP and KCIII ECP are not necessarily coterminous. The latter always follows the most seaward route while the former does not.

In the next mile or so, for example, the official South West Coast Path – as marked on Google Maps – now takes a higher line, eventually joining a road close to the south-eastern extremity of the Prison.

There was no obvious signage though, so we continued along the undercliff past Little Beach. Someone had used stones to mark out what looked like ‘Lola 4 Lars’.

A little way beyond we found a path upwards signed ‘Coast Path’, emerging slightly further along the prison’s perimeter. This was once the official SWCP route according to my guide, though that was last updated in 2016.

Doubling back in the direction from which we maybe should have come, we went to the Jailhouse Diner, run by prisoners. We bought two coffees and two pieces of fruit cake for £8, the cake served by the inmate who had baked it. (Between you and me, it had a slightly soggy bottom, but I wouldn’t have dreamed of telling him so!)

Portland Prison was established in 1848, primarily to supply convict labour for Admiralty Quarries, from which stone was hewed to build Portland Harbour.

It became a Borstal in 1921, then a Young Offenders Institution in 1988 and a Category C Adult/Young Offenders’ Prison in 2011. Some 500 prisoners occupy seven different blocks.

A highly critical inspection in 2019 was followed by a rather better outcome in 2022.

Resuming, we skirted the high perimeter wall, itself listed, along with several other features of the Prison. The atmosphere was grim, threatening and oppressive, and I was glad not to linger on what was suddenly a cold, grey afternoon.

I tried not to notice anything untoward happening in a van parked beside the wall – and felt a twinge of hypothetical guilt on spotting a ‘report anything suspicious’ sign later.

The Coast Path briefly joins Incline Road, passing an engine shed for the locomotives that formerly served the Admiralty Quarries, then veers off left, seemingly determined to avoid the north-east extremity of Portland.

This has been out of bounds since Portland officially became a Royal Navy Dockyard in 1914. When the Dockyard closed in 1959, the area was initially retained as a Naval Base. When that finally closed in 1995, the site was sold to Langham Industries, which operates Portland Port Ltd.

The infamous Bibby Stockholm was moored here until January 2025, but I don’t pretend to understand why such heightened security remains essential. The locals are reputed to call this north-eastern corner ‘the Forbidden City’.

The ‘Portland Neighbourhood Plan’, part of the Weymouth and Portland Borough Council’s Local Plan, says:

‘Cemetery Rd to the Engine Shed, Grove – is a route of some 1.5 km, which cannot be fully accessed due to the Port’s security concerns. If fully open and repaired, it would open up the East side of Island and improve the SW Coast Path offer. The road up to the Cemetery is in reasonable condition but the old army road beyond this is badly overgrown and in poor condition. A potential route from here using the pathways close to the cliff face, the track bed of the High Level Railway and appropriate routing around the open ground adjacent to Nicodemus is potentially viable, subject to detailed assessment. The route in places would require additional security fencing to the seaward side.’

That Plan was adopted ten years ago, so don’t hold your breath for those unspecified ‘security concerns’ to be resolved any time soon!

You’ll have to make do instead with this online tour.

The official route passes through a desolate no man’s land, courtesy of all that quarrying.

It flirts briefly with the former RAF Portland, now hosting a community farm and unofficial campsite, before reaching the entrance to the Verne Citadel, built between 1857 and 1881 to defend Portland Harbour. This is surrounded, on its southern and western sides, by a huge ditch, some 20 metres deep and 40 metres wide.

Part of the Citadel houses another prison: The Verne. This Category C institution, first established in 1949, presently hosts some 600 sex offenders, including the artist formerly known as Gary Glitter.

We joined the Merchants Railway route down through Verne Common Estate. This opened in 1826, making it the earliest rail service in Dorset.

Initially horse-drawn, it was later cable-operated, bringing stone down two miles from the quarries to a pier at Castletown, below. It closed in 1939.

The lower slopes are dominated by the gutted shell of a large block, formerly part of the ‘Hardy Complex’. This Royal Navy accommodation was sold on to developers when the Navy left the Harbour. One block was fully renovated by 2008; the other remains an empty eyesore, despite planning permission to convert it into much-needed housing.

We skirted Portland Castle, built by Henry VIII between 1539 and 1541, also as one of a pair, the other being Sandsfoot Castle on the Weymouth side of the Harbour.

At the start of the Civil War it was in Parliamentary hands, but was captured by Royalists in 1643. It was later besieged twice before surrendering to Parliamentary forces in 1646.

After the Napoleonic Wars it was converted into a private residence, only to revert to accommodation for military officers. In 1955 it opened to the public, though part of the grounds was retained by the Naval helicopter base.

This photograph shows part of the Castle, with the ‘Hardy Complex’ lurking behind.

From here the Coast Path heads round Osprey Quay which hosted the sailing events for the 2012 London Olympic Games. We admired the Crabbers’ Wharf Holiday apartments and the multi-storey boatpark.

We stopped beside the memorial for Danny the Dolphin who died in 2020 after being struck by a ship; the information board about ‘Tom the Torpedo’; and the memorial commemorating the 29 sailors killed when a boat belonging to the aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious sank in the Harbour in 1948.

By 15:15 we were crossing Ferrybridge once more, this time along the starboard side, away from Chesil Beach.

When our bus reached Weymouth Town Centre it was starting to rain. We took shelter in the Doghouse Micropub where we made the acquaintance of the charming Skye, whose house it is. A trio of local CAMRA worthies discussed other favourite watering holes nearby.

Afterwards it was another quiet night in.

Day 5: Ferrybridge to Osmington Mills

Next morning, we again reached Ferrybridge by around 09:00. It had been raining but, as we left the bus, the rain had stopped and the sky was already brightening.

The first part of our route passed around Smallmouth Beach, the back wall stacked with innumerable brightly coloured canoes. We were now following the Rodwell Trail, retracing the route of the former Weymouth to Portland Railway (see above).

Passing Castle Cove Beach, which hosts a large sailing club, we reached the ruins of Sandsfoot Castle, which became derelict as early as 1725.

It too appears in a Victorian novel: ‘The Poisoned Cup’ (1876) by Joseph Drew (1814-1883), a resident of Weymouth.

It doesn’t seem very good:

‘When Charles had explained to Lord Burleigh the attachment that existed between himself and Jessie and the particulars of Sir John Trenchard’s proposal for her hand his noble kinsman not only highly approved of his determination to proceed to Weymouth but placed in his hands a despatch which had that day arrived at Court announcing the death of Sir John Bond and consequently the vacancy of the Governorship of Sandsfoot Castle. “And now,” continued Lord Burleigh, “I will endeavour to secure for you this appointment so that you may retire from one occupation to another without quitting the service of our noble Queen”.’

We were now amongst some of the most desirable residential properties in town, our attention drawn by listed Portland House, built in 1935 to a ‘Hollywood Spanish design’.

Soon afterwards we emerged on to Bincleaves Green, beside the Wyke Coastguard Rescue lookout. This contains a monument to Sir Thomas Fowell Buxton (1786-1845), the Weymouth MP, brewer and abolitionist.

We were now following the Elizabethan Way, set out to mark Queen Elizabeth II’s Silver Jubilee in 1977. It took us through Nothe Gardens, towards Nothe Fort, a D-shaped fortification occupying the end of Nothe Peninsula.

This was built between 1860 and 1872 and comprises three storeys: magazines at the bottom; in the middle, heavy gun emplacements, with gunners’ accommodation alongside; and ramparts at the top, from which lighter weapons could be fired.

In 1961 it was sold to the Borough Council, which initially intended to develop it into a luxury hotel, though it is now a museum and tourist attraction.

We made our way down to Stone Pier Café. Naturally enough, this sits adjacent to Stone Pier, a short extension to the peninsula, jutting out into Weymouth Bay at the entrance to Weymouth Harbour.

Here we met Sonia once more, accompanied by Ernie, her lovely old dog. He has a dodgy ticker.

After coffee, cake and chat, we set off together alongside the harbour entrance, past Weymouth Gig Rowing Club and Weymouth Lifeboat Station. A lifeboat was first stationed here in 1869 and the original stone-built lifeboat station is still standing, alongside a modern boathouse built in 1996.

Another small peninsula sits on the opposite side of the harbour entrance, marking the start of Weymouth Esplanade and accommodating Weymouth Pavilion.

The original Pavilion opened in 1908. It was requisitioned during the Second World War, reopening as The Ritz in 1950. Only four years later, this largely wooden structure was severely damaged in a fire. The present Pavilion opened in 1960 but has several times been threatened with closure and demolition.

The Coast Path runs along the southern edge of the Harbour, crossing Town Bridge, then heading back in a seawards direction on the northern side, along Custom House Quay, finally joining the Esplanade near an impressive sweep of Georgian townhouses.

A little further down, the beach donkeys stood in readiness for their first customers. The Jubilee Clock Tower, constructed in 1887, looked resplendent in the bright morning sunlight.

We continued round the broad sweep of the Bay, eventually coming abreast of the RSPB Lodmoor Nature Reserve, which occupies a saltmarsh behind the seafront. Heading uphill at Overcombe, we reached the grass down above Bowleaze Cove by 12.15, stopping there for lunch on one of the benches.

Bowleaze is dominated by its Holiday Park – which seems to have expanded since I last visited some twenty years ago – and by the immense, low-slung, art deco-ish ruin of the Riviera Hotel.

Built in 1936-1937, its first owner went bankrupt prior to completion, so it did not open until the 1939 summer season. In October that year it took in 135 evacuees, disabled children from London special schools, along with their teachers and medical staff.

By the late 1950s it had become part of the Pontins group, then it was sold again in 1999 and refurbished, then sold and refurbished once more in 2009. At the end of 2020 it was put up for sale with an asking price of £5.5m, but there was no buyer.

In February 2022 Storm Eunice caused the ballroom roof to collapse. By the summer of 2023, it was said to be closed for another round of extensive refurbishment but, when we passed by, it was mostly unoccupied and obviously in poor condition. Rumours of imminent sale continue to swirl.

Our route continued across fields, rounding Redcliff Point and passing close by the PGL facility at Osmington Bay. Inland, there is the Osmington White Horse, cut into Osmington Hill in 1808 to celebrate the regular visits made by George III.

We now faced a choice: either speed ahead to catch the next bus back into Weymouth, or else take our time and wait for the next bus but one.

We chose the second option, immediately descending to the shingle beach at Osmington Bay for a paddle. It was completely deserted. We disturbed an egret stalking along the water’s edge, also enjoying the solitude.

Unfortunately though, more people arrived fairly quickly. A group of three sat not too far away, putting our paddling to shame by wading in up to their chests.

Ultimately resuming, we reached Osmington Mills at roughly 15:00. John Constable (1776-1837) spent his honeymoon hereabouts in 1816, completing several drawings and an oil painting of Weymouth Bay.

The Coast Path heads down Mills Road, skirting The Smugglers’ Inn before striking out towards Durdle Door and Lulworth Cove. We recconnoitred the start of our next and final section, then climbed down on to the beach, hoping to circle back to our starting point.

But the going was tricky for tired feet, so, doubling back, we visited the handy public toilets before climbing a mile or so up Mills Road to reach the A353 at Osmington.

On the way we disturbed a young woman putting a horse through its paces in a show jumping ring.

We reached the bus stop in good time for the X54 service back to Weymouth. The top front seats were occupied by a woman and a Chinese mature student she had been guiding around the area. She struggled to sustain the small talk required, patting him awkwardly on the shoulder before descending at her stop.

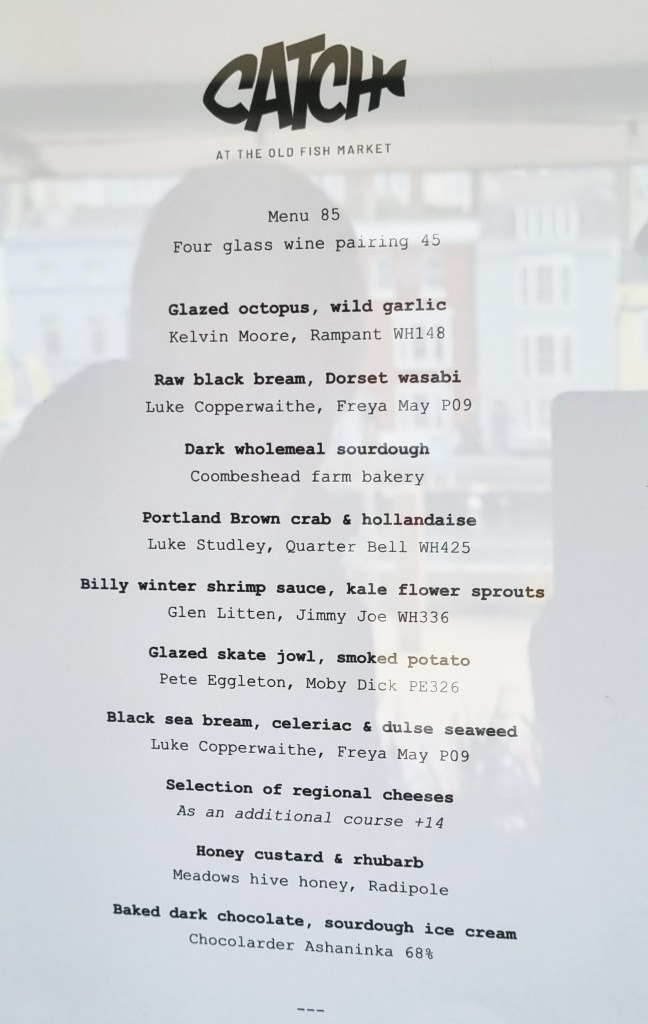

On this final evening our celebratory dinner was provided by Catch: a fish-based tasting menu with paired wines and optional cheese. It was a bit too piscatorial for me, but I enjoyed it nevertheless.

Home

Next morning there was ample time to pack and eat our ‘part one breakfast’ before heading down to Coffee Jazz for coffee and ‘part two’.

We pulled our cases along the Esplanade once more, stopping to watch a group of players and officials set up a beach volleyball court. They were digging deep holes in the sand to take the stanchions at each end of the net, measuring constantly to ensure they aligned.

At the Station we caught the 11.21 service to Bournemouth, picking up a replacement bus service to Southampton Central, and finally connecting there with a train through to Woking.

We were home by mid-afternoon.

TD

April 2025

Leave a comment