This is the third in a series of posts about music that is personally important to me.

I intend to write twelve posts in all – one per month throughout 2025 – each post connected in some way with its predecessor; the final post somehow linked with the first.

These connections are being forged as I go along: I have not pre-planned the pieces of music I am going to choose. It follows that some of the connections may end up being less than robust.

This month’s choice is Sweet Fanta Diallo, by Alpha Blondy. There is an original and a remastered version. Both are equally good.

In this case I can make a clear connection between my new selection and my previous choice, Autorail, by Orchestre Baobab.

The lyrics of Autorail were written by Medoune Diallo (1949-2018) – and he was most probably the featured vocalist on Autorail too – while the subject of Blondy’s song also has the surname Diallo.

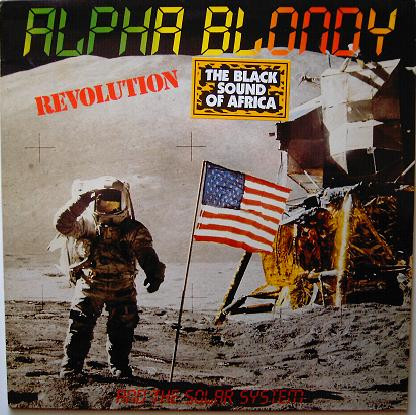

Sweet Fanta Diallo was the opening track on Alpha Blondy’s fifth album, Revolution, released in 1987, and also as a single that same year. Both were officially credited to ‘Alpha Blondy and the Solar System’

I have no personal memory of the song from the time of its release, although I do recall hearing other Blondy tracks around that time, especially Brigadier Sabari.

It’s highly likely that I did encounter Fanta Diallo several times in the late 1980s, but I didn’t come to treasure the song until after my own personal struggle with poor mental health.

Unlike my two previous choices, this one is driven by my appreciation for the lyrics rather than the musical quality, though I have no complaint with the latter. It also helps that the lyrics are in English!

Alpha Blondy

Alpha Blondy is, of course, a stage name.

He was born Seydou Koné on 1 January 1953 in Dimbokro, Ivory Coast, the eldest son in a family of nine children. Up to 1962, he was cared for by his grandmother, but then joined his parents in the town of Odienné where he spent the next decade.

He attended high school, intending to become a teacher. Calling himself ‘Elvis Blondy’, he formed a band with fellow students, but gave so much time to music that he was expelled.

In 1973 he hitchhiked to Monrovia, Liberia, where he lived for a year, giving French lessons and learning English. But he wanted to leave Africa for the United States, and finally arrived there in 1976.

He enrolled in a New York business school to learn business English, then at Hunter College, where he took further language classes before joining a foreign students’ programme at Columbia University.

During this time, he encountered Rastafarianism and was heavily influenced by Burning Spear’s 1976 concert in Central Park.

He was, allegedly, twice married while living in the United States, first to Kathleen, a white woman whom he quickly divorced, second to Carroll, a black Jamaican.

He made some steps musically, primarily through contact with the Jamaican musician and producer Clive Hunt. They recorded eight songs at the Eagle Sound studio in Brooklyn, New York, but these were never released.

During this period, he experienced a mental health breakdown, possibly assisted by the drug habit he had developed, and was committed to a psychiatric hospital.

He asked to be repatriated to his home country and, on his return, was admitted to the Bingerville Psychiatric Hospital in the outskirts of Abidjan.

On his release he began playing music again, calling himself ‘Alpha’ to mark this new beginning.

Shortly afterwards he re-encountered an old friend, Roger Fulgence Kassy, who presented a show on RTI (Ivorian television) called ‘Premiere Chance’. This gave many young Ivorian musical artists their first break. Blondy performed four songs for the show, one Burning Spear cover and three of his own compositions.

Kassy worked with a close-knit group of presenters and producers known as ‘Studio 302’, one of whom was Georges Tai Benson. On the strength of ‘Premiere Chance’, Benson agreed to produce Blondy’s first album, Jah Glory, which appeared in 1982.

Blondy was backed by a group of studio musicians, under the name ‘The Natty Rebels’. The track Brigadier Sabari, which condemns the police violence that Blondy himself experienced, became an anthem of protest, cementing his fame.

Three further albums followed in rapid succession – Cocody Rock in 1984, Apartheid is Nazism in 1985 and Jerusalem in 1986 – before Revolution appeared in 1987.

This was a major departure from Blondy’s previous work, often with a lighter, mellower sound, adding violin and cello parts alongside the guitar and horns. It also featured the legendary Cameroonian sax player Manu Dibango (1933-2020).

Since then, Blondy has produced numerous studio albums, continues to perform worldwide and supports various humanitarian causes. He has also been affected by further mental health issues, notably in 1993, when he again entered a psychiatric institution.

Sweet Fanta Diallo

Blondy recalls scenes from his past relationship with a young woman called Fanta Diallo, but his memories blend possible reality with a mystical perspective:

‘Fanta walking on the rainbow, now!

Fanta shivering in moon light waves

Fanta hugging me on the mountain top

Fanta kissing me on the burning rocks.’

One day, Fanta disappears, causing Blondy to wonder repeatedly where she’s gone. He recalls her in similar, but slightly different scenarios:

‘Fanta walking on the rainbow, now!

Fanta kissing me on the burning rocks

Fanta kissing me in the candlelight

Fanta hugging me on the burning rocks.’

The musical accompaniment is jaunty, bouncy, happy, almost childish, the tune driven along by the rhythmic parp-parp of a tuba, over which keyboards and strings – violins and cellos – predominate.

But then, suddenly, a completely different mood, a heavy poignancy, is superimposed on this light-hearted, even slightly naïve little ditty:

‘The last time I saw her

Psychiatric hospital; psychiatric hospital

Psychiatric hospital; psychiatric hospital

Now I know I did you wrong

Now I know I did you wrong, wrong, wrong.’

And, as the tune fades out, Blondy is seemingly declaring his love and longing, but he makes this declaration to the rainbow on which Fanta walked, rather than to her directly:

‘Yes, I love you rainbow

And I love you rainbow, ray

Yes, I love you rainbow, rainbow ray

Yes, I love you rainbow ray

Never leave me rainbow

You got to lead me rainbow ray

Please help me rainbow

You got to lead me rainbow ray

Please help me rainbow

You got to lead me rainbow ray.’

It seems there are two dominant interpretations of this song.

In one version, Blondy has returned from America in poor mental health. He spends several months in a psychiatric hospital. When finally well enough to leave, he wants to return to thank Fanta Diallo, a beautiful and caring nurse who was central to his recovery, only to learn that there is no-one by that name on the hospital’s staff.

In the alternative and more likely version, which Blondy himself has advanced, Fanta Diallo really existed. He had a relationship with her before he left for America. Indeed, she was instrumental in helping him achieve his ambition to leave Ivory Coast for the United States.

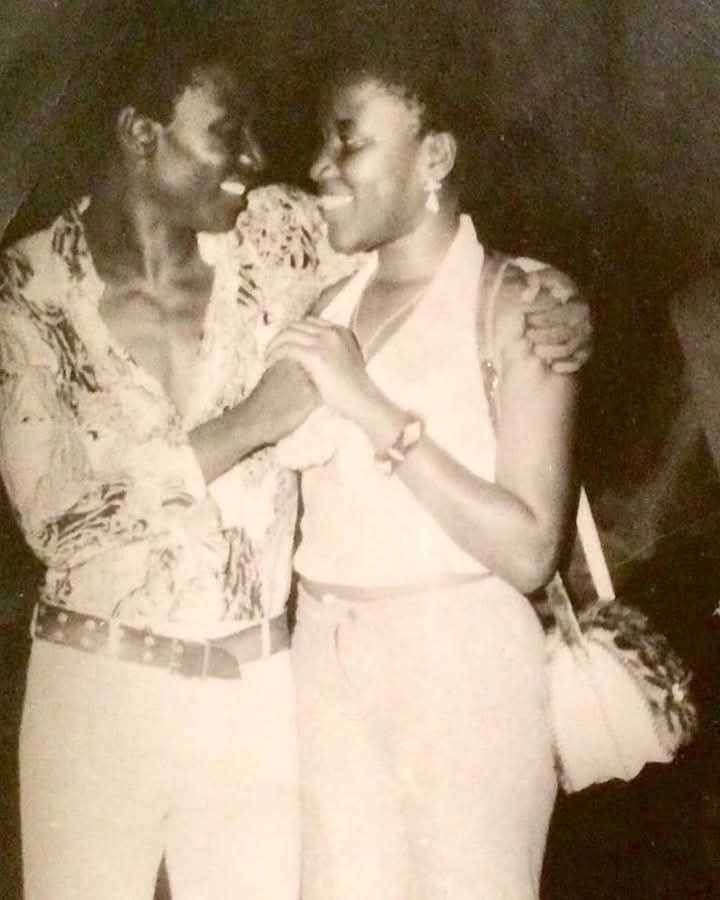

There is even a photograph published online, purporting to show the two together in 1973.

Fanta is said to have been born in Ivory Coast’s second city, Bouaké. Her father was an inspector on the railway linking Ivory Coast to Burkina Faso and Niger (another connection with Autorail). When she met Blondy, she was a student at the Lycee Sainte-Elisabeth in Korhogo.

But, once Blondy arrived in America, he forgot about her completely, did not write and so effectively terminated their relationship. As noted above, he had at least two serious relationships with other women during his residence in the United States.

On returning to Abidjan, while attending the Bingerville Hospital, he finally faced up to this behaviour, bitterly regretting the way he had treated Fanta. Might he even have wanted to revive the relationship, perhaps?

She visited him while he was in the psychiatric hospital. But she had already married someone else and had a completely new life. Blondy’s chance had gone.

Fanta is said to have died in 2004, aged only fifty, and is buried in the Williamsville Cemetery in Abidjan. Blondy is reputed to pray regularly at her grave, though that may be apocryphal.

Personal relevance

Reggae has attracted me since my first exposure to it.

That dates to when I received, probably as an Eleventh Birthday present, a small transistor radio, equipped with medium and long wave and a telescopic aerial. It had a black leather case with white stitching.

A new world of music suddenly opened up for me, as I listened covertly to Radio Luxembourg under the covers.

The reggae songs I particularly remember from this era included ‘Israelites’, by Desmond Dekker (1968/69), ‘To Be Young, Gifted and Black’ by Bob and Marcia (1970) and ‘Double Barrel’ by Dave and Ansel Collins (1971), all of which made the upper reaches of the British charts.

I lost touch a little during my Radio Seagull/Radio Caroline years (roughly 1973-1975). By this time, I had in my room the family’s old Bush Radio, with valves and a large veneered cabinet. It was rigged up to a wire aerial that passed round the loft, and I spent hours searching out distant short wave stations.

But I digress.

My interest in reggae revived during a subsequent disco phase, with occasional punk and pub rock influences. Police and Thieves was a particular favourite, whether the original version by Junior Murvin or the cover by The Clash.

When I reached UEA in 1978, Steel Pulse and the fledgling UB40 were ubiquitous.

Later on, we frequented a reggae disco in Norwich, near the Art School, where there was much skanking to Jamaican dub classics. Black Uhuru’s ‘Shine Eye Gal’ and ‘Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner’ were particular favourites.

A third strand of influence was supplied by Linton Kwesi Johnson, whose albums Forces of Victory (1979), Bass Culture (1980) and LKJ in Dub (1980) were widely played in student circles.

By the mid-80s, I was visiting my brother in Hulme, Manchester. He lived in one of the Crescents while taking a degree in sculpture at Manchester Poly.

We would sometimes go to the neighbouring PSV ‘Caribbean Club’ for some serious Dub, played through giant speakers that vibrated inside your chest cavity, and as many cans of Red Stripe as we could afford.

But I didn’t encounter African Reggae until I heard the music of Alpha Blondy and Lucky Dube on Charlie Gillett’s world music radio show. Charlie has featured in both previous episodes of Ouroboros.

Initially, it was Blondy’s Brigadier Sabari that made the biggest impression but, over the years, I have come to prefer Sweet Fanta Diallo.

For me, it captures the bittersweet nostalgia of a man looking back to an idyllic former relationship – recalling with some regret a love he has lost and a past he can never recapture.

Until I researched this post, I’d always assumed that his betrayal of their love – ‘now I know I did you wrong’ – had damaged Fanta Diallo’s precarious mental health, and that it was she who resided in the psychiatric hospital.

But that is far less important than the emotions conjured and played upon by the song.

Blondy’s recollections seem a mixture of scenarios that might actually have happened and a more mystical vision arising in his imagination.

My imagination can picture these two young lovers, bathing in moonlit waves and jumping between rocks heated by the sun until they were burning hot. Both these recollections would place the couple on the coast, so perhaps near Abidjan rather than inland, where Blondy and Diallo lived.

There are mountains in Ivory Coast too. Mount Nimba, in the extreme west, on the border with both Liberia and Guinea, stands at 1,752 metres. It is quite conceivable that these lovers climbed to the top of an Ivorian mountain and embraced there.

But Fanta cannot actually have walked upon a rainbow, so that must be a vision.

Indeed, Fanta seems to become the rainbow. Like a rainbow, she melts away under the sun. And, in the final part of the song, Blondy declares his love for this personified rainbow, which now embodies Fanta’s spirit. He asks it never to leave him, to lead him and help him through the remainder of his life.

The rainbow is, of course, deeply symbolic, representing the connection or bridge between earthly existence and what lies beyond, between physical, human love and supra-human spiritual love. It also denotes renewal, through the appearance of the sun after rain, expressing hope for better times, commitment to new beginnings.

Despite that sudden, dismal recollection of the psychiatric hospital, which plunges both the listener and the singer into deep remorse, the song ends on this positive, uplifting note.

And, as with all great music, the whole is vastly greater than the sum of its parts.

TD

March 2025

Leave a comment