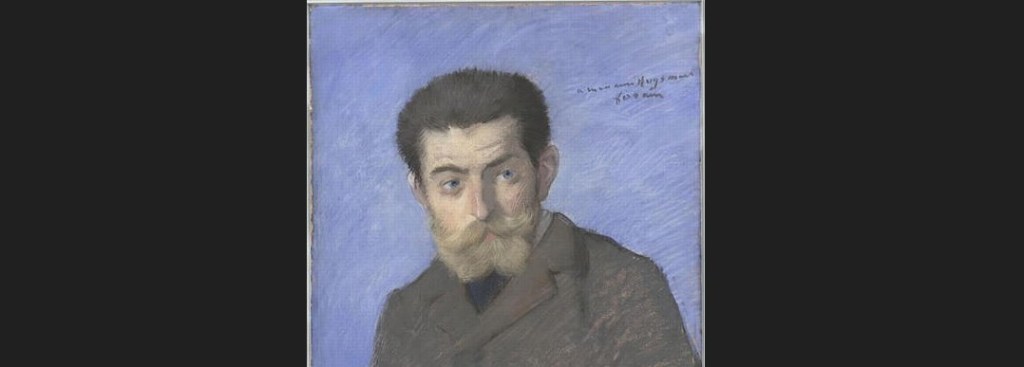

Novelist Joris-Karl Huysmans (1848-1907) is best known for ‘Au Rebours’ (Against Nature) (1884), widely regarded as a seminal work in the French Decadent tradition.

‘La-bas’ (The Damned) was published seven years later in 1891. I read the 2001 translation for Penguin Classics by Terry Hale.

Huysmans was employed as an administrative civil servant in the national office for criminal investigation, attached to the French Ministry of the Interior. He probably drafted much of this novel during working hours, using Ministry notepaper, even utilising material drawn from official criminal files.

Given the sensational nature of The Damned, there was surprisingly little controversy upon publication, although the book was banned for a while from railway bookstalls.

Don’t read it if you are of a particularly sensitive disposition, or easily shocked. Be prepared for the graphic depiction of sadistic violence and Satanic ritual.

The principal character is Durtal, a writer and a version of Huysmans himself. He is cynically disillusioned by contemporary life, finding himself drawn instead to the medieval world view.

The tone is set early, by an extended description of a Crucifixion – from the Tauberischofsheim Altarpiece, painted by Matthias Grunewald (c1470-1528).

This hammers home the sadistic dimension of Christian belief with pornographic precision. It is distinctly unpleasant, not easily forgotten. But perhaps that helps to explain the success of Christianity as a religion.

Durtal has begun a biography of Gilles de Rais (c1405-1440) a prominent nobleman who fought alongside Joan of Arc. But, afterwards, he became a monster, ultimately tried and executed for heresy, sodomy, rape and the murder of at least 140 children.

We listen to Durtal’s graphic reimagining of these crimes, as he charts the slow disintegration of his subject.

Huysmans also describes Durtal’s own life while he is engaged in writing this book. It features several conversations with a trio of friends, mostly arising after sumptuous dinners given by Carhaix, a bellringer. He lives with his wife, (who cooks the dinners merely), in an apartment beneath the bells in the Catholic Church of Saint Sulpice. From time to time, he exits to toll them.

These discussions are theological in nature, as Durtal strives to understand the theory and practice of contemporary Satanism, as observed in late Nineteenth Century Europe. He believes that this will help him understand the Fifteenth Century perspective of Gilles de Rais.

By a huge coincidence (or is it predestined?) he becomes irresistibly attracted to Madame Chantelouve, the wife of an acquaintance, who pursues him and with whom he begins a sexual relationship.

She turns out to have Satanic leanings and is closely associated with the leading Parisian practitioners.

At the book’s climax, she takes Durtal to witness a Black Mass and, sexually aroused by the experience, immediately copulates with him:

‘She grabbed hold of him, took possession of him, and initiated him into obscenities whose existence he had never suspected; she was like a ghoulish fury. But when, eventually, he was in a position to escape, his heart stood still: for he saw that the bed was littered with fragments of the Eucharist.’

He terminates the relationship.

The Crucifixion and the Black Mass act like bookends. In between them, Huysmans blends obscure erudition and occasional sensationalism to create a densely textured narrative that can seem claustrophobic and stifling. One is unwillingly fascinated; one somehow longs to escape.

The Damned attracts and repulses in equal measure but, like Against Nature, it is a classic example of Decadent literature, helping the reader to understand more clearly the prevailing zeitgeist in fin de siecle Paris.

TD

March 2025

Leave a comment