After a seven month hiatus, we returned to the South Downs Way at the end of January 2025, our trip timed to coincide with Tracy’s Birthday.

We’d been scanning local weather forecasts for several days, fearing more high winds and driving rain, given the series of winter storms that had been battering Britain. All my waterproof gear was packed, along with a supply of plastic bags.

But, in the event, the weather was mostly benign. We got wet only during the final hour of the first day, while the second was bathed in glorious winter sunshine.

We adhered exactly to our plan: on day 1, a complex early morning journey to Cocking, followed by the 19.3km to Amberley and our overnight stop; on day 2, a further 9.7km to Washington before heading home.

The total distance was 29km – almost exactly 18 miles.

Day 1: Cocking to Amberley

Arriving at Woking by 08:30, I had time to collect a coffee and warm almond croissant from Starbucks before joining the Portsmouth Harbour via Guildford service.

Alighting at Haselmere Station, we crossed to await the Midhurst bus. At the stop we found two lively young mums and their two equally lively toddlers, all on their way to the library.

The service into Midhurst ran a little late, and we were puzzled by the apparently complex transfer to our second bus envisaged by Google Maps, only to discover the two stops were adjacent.

The driver of our second bus, headed to Chichester, was just finishing her roll-up before setting off. She may have been anticipating further stress since we heard that the previous service hadn’t turned up!

We arrived at the South Downs Way stop, on the A286 south of Cocking at approximately 10:20. It was chilly, dry and reasonably bright.

Making our way up Hillbarn Lane, we reached a cluster of farm buildings and timber merchants. The farm shop was closed. I struggled to spot the tap at this water point, having to stare hard for several seconds before it registered.

After pausing to admire the view across the valley, we resumed our ascent, now into woodland, soon arriving at this homemade sign advertising the Unicorn Inn at Heyshott.

On entering a large clearing, we spotted a handful of deer, but they vanished in an instant, leaving this deerless expanse – and a strangely-shaped tree.

This land is part of the Cowdray Estate, some 16,500 acres, owned by the 4th Viscount Cowdray, Michael Orlando Weetman Pearson. It incorporates a mansion – Cowdray House – a golf club, a polo club and 330 houses.

Pearson helped produce ‘Sympathy for the Devil’ (1968), Godard’s avant garde film featuring the Stones. According to the Daily Mail, he split from his second wife, Marina Rose, nee Cordle, in 2023.

She is the daughter of a former Tory MP, reportedly an adviser to the Oxford Centre of Mindfulness, a proponent of silent meditation and ‘Qigong’. This turns out to be a mixture of tai chi and meditation, with rhythmic breathing thrown in for good measure.

We began to encounter notices about a resident flock of Badger Face Sheep, which had been prepared by the Graffham Down Trust.

The sheep are a hardy, Welsh mountain variety with two possible colour schemes: a black belly or a white belly. The former are three times more numerous.

The Trust was formed in 1983 by residents of the nearby village of Graffham, to preserve and protect the downland, including its indigenous flora and wildlife. They had wanted to restrict the clearance of downland for arable farming.

Part of the land the Trust now oversees is the Dimmer Reserve, named after its Honorary President and former Reserves Manager, Paul Dimmer, who sadly died of cancer in 2022.

We also passed a handy information board about the archaeological features up here, including two Bronze Age barrows. One is a 20-metre bowl barrow surrounded by a ditch; the other a rarer 15-metre bell barrow. There is also a cross dyke thrown in for good measure.

We stopped nearby, sitting on a handy tree trunk to take our morning coffee. We’d filled our flasks before setting out. Two mountain bikers passed by, descending towards Cocking, deep in conversation.

Soon after resuming, we reached a signpost, supplied by the Friends of the South Downs, the charitable membership organisation dedicated to protecting the Downs.

It developed out of a walking group, the Society of Sussex Downsmen, first formed in 1923. Three years later, they managed to prevent a mysterious secret syndicate from building a new town above the Seven Sisters cliffs.

We had expected to stop for lunch somewhere in the vicinity of Littleton Farm, a little further on. But, emerging from the woodland, we came upon a bench overlooking the countryside below, extending northwards towards the North Downs. The horizon was shrouded in mist.

We were close to Crown Tegleaze which, at 255 metres, is the highest point on the South Downs in Sussex, exceeding Ditchling Beacon by a full seven metres.

Adopting the ‘bird in the hand’ principle, we had our sandwiches here, taking in the beauty of our surroundings.

On the descent we passed these signs, explaining that the farm we were passing through belonged to Linking Environment and Farming (LEAF), a charity whose mission is:

‘To inspire and enable more circular approaches to farming and food systems through integrated, regenerative and vibrant nature-based solutions, that deliver productivity and prosperity among farmers, enriches the environment and positively engages young people and wider society.’

Beneath, there is the insignia of a Red Tractor Farm.

Red Tractor declares itself:

‘…the UK’s largest food chain assurance scheme, setting standards and ensuring compliance at every stage of the chain, to reassure consumers that food is produced safely and responsibly.’

Advancing into the field, we saw that our way lay across it, but the SDW waymark had taken a tumble.

On reaching Littleton Farm and its Campsite, the wisdom of our early lunch was confirmed. The farmyard gate was locked, the café – provided by Cadence Cycle Club – closed until April.

There wasn’t even a bench available for weary hikers.

Crossing the busy A285, we set our sights upon the vista ahead. As we climbed, our view across the misty lowlands opened up once more, as we came abreast of the two large radio masts at Glatting Beacon.

There are also several tumuli marked in the fields hereabouts.

We passed an uncommunicative woman with two very bouncy dogs, then spotted a bench, carved from a tree trunk, at the gate marking the Slindon Estate.

Placed neatly at one end, though upside-down, we found a pair of ladies’ Karrimor walking boots.

While drinking our afternoon coffee, we attempted a rational explanation for their presence.

Our best guess was that someone female had walked up through the mud, changed into running shoes which they had carried up with them. They had then commenced a circuit, expecting to rendezvous with their boots on completion, turning them bottom-up to protect against rain showers.

Elementary, my dear Watson…or perhaps there was a less rational explanation!

While we pontificated, the uncommunicative woman returned with her dogs and, hanging her jacket over the fingerpost, removed a layer before setting off again. She remained uncommunicative.

The Slindon Estate is National Trust land, comprising some 3500 acres. Slindon itself lies further south, close to Fontwell. Hilaire Belloc (1870-1953) spent his childhood there.

Passing a field full of inquisitive sheep, we arrived at this signpost, denoting a Roman road, 57 miles long, connecting Chichester (Noviomagus Reginorum) with London (Londinium). It was subsequently called Stane Street (‘Stane’ being an outmoded variant of ‘Stone’).

There is a Neolithic Camp at Barkhale, on the slopes of Bignor Hill, one of about 70 similar constructions across the British Isles. Their use is uncertain, though they may have been fortified settlements of some kind. This one probably dates from around 3700BC and its boundary ditch encloses an area of almost seven acres.

A sign marks the way to Bignor Roman Villa, which boasts well preserved mosaic floors. A wooden farm building was built circa 190AD, later replaced by a four-roomed stone structure, further extended between 240 and 290AD.

More extensions were added throughout the first half of the Fourth Century, until there were some 65 rooms. The remains were rediscovered in 1811.

Just before descending towards Houghton and Amberley, we found Toby’s Stone.

It is inscribed:

‘Toby 1888-1955:

Here he lies

Where he longed to be

Home is the sailor,

Home from the sea

And the hunter

Home from the Hill.’

Those lines are from ‘Requiem’ by Robert Louis Stevenson, but his authorship isn’t acknowledged.

The stone commemorates one Toby Wentworth-Fitzwilliam, once secretary to the Cowdray Hounds, more properly known as George James Charles Wentworth-Fitzwilliam. He was later the director and secretary of the British Field Sports Society.

He might have been the Tenth Earl Fitzwilliam, but the title passed elsewhere.

Apparently, he had been born following a marriage in Scotland, without ‘benefit of clergy’. It was valid under Scottish law, but not under English law. There was a later ceremony in England, but it was post Toby. His mother, allegedly upset that he had chosen a governess to marry, is said to have personally declared him illegitimate. A 1951 court case found against him.

This brought to mind the plot ‘Man and Wife’ (1870), a novel by Wilkie Collins.

There are other commemorative markers up here too, including a wooden one recalling ‘Henry Claude Strathern Evill (1931-2024)’, another landed gent.

We began the slow descent, passing Egg Bottom Coppice to our right.

As we did so, a land rover passed by, pulling a cartload of oddly complacent sheep. It seemed improper to photograph them on the way to their doom but, as it turned out, they were only hitching a ride to a field further down the hill.

The water meadows below looked extensively flooded, but most of them seemed to lie above Amberley, approaching Bury.

It was a long slog until we reached the lane just above Houghton, which is visited by the Monarch’s Way but not the SDW.

Several cars seemed to be hurtling along this road, and it didn’t help that another was parked at the best crossing place, the owner removing her wellingtons.

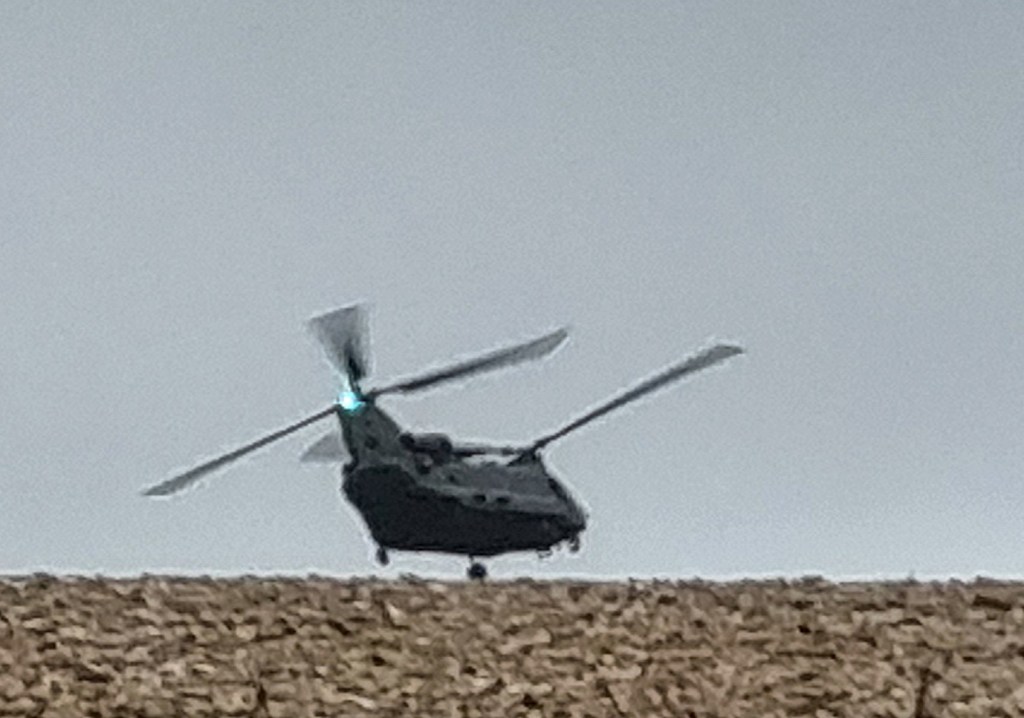

While we skirted around her, a Chinook helicopter swooped low over the road, continuing above the field to our right.

Once across, we found ourselves on a muddy track heading down towards the River Arun. We noticed a mysterious rectangular box in a tree, hanging from two pink ties, but our efforts to guess the solution to this second mystery were less inspired.

The rain began in earnest while we approached the floor of the valley. As it grew heavier, we made the decision not to stop to don our waterproof trousers.

The route across the water meadows was straightforward, but we had to negotiate a seriously muddy curve of the riverbank, before crossing to the opposite bank via a footbridge.

Skirting the sewage works, we went under the railway line and across the B2139, following the route round to the top of Mill Lane.

Here we turned, crossing the B2139 a second time before heading along School Road and the High Street until we reached our destination. It was almost exactly 16:00.

Overnight in Amberley

According to the Parish Council, Amberley’s name may be derived from the Old English for ‘a measure of volume’.

There was likely a small Roman settlement here and possibly a Saxon wooden church on the same site as St Michael’s, whose oldest sections date from the mid-12th Century.

The Bishops of Chichester had a palace nearby. Initially a manor house, it was fortified in 1377, becoming Amberley Castle. The last Bishop to occupy it died in 1536. By the time of the Civil War, it belonged to a Royalist, John Goring, causing it to be attacked by Parliamentarians. These days it is a hotel.

By the 18th Century, the Village had become an important stopping place on the main coach road from Arundel to London. The nearby chalk pits were established early in the Nineteenth Century and, at their peak, employed upwards of 100 men. By the mid-19th Century, Amberley had a population of 650 and supported eight public houses. The railway station opened in 1863.

Writer Noel Streatfield lived here as a child and the artist Edward Stott settled here from 1887 until his death in 1918. Illustrator Arthur Rackham also lived hereabouts for a while.

The Black Horse dates from the early Nineteenth Century. It closed in 2012 and was saved from redevelopment as housing by a local action group. The present owners bought it in 2016, reopening after extensive refurbishment.

Making our way inside, we tried our best not to spread too much mud and water on the floor. A friendly elderly couple asked whether we were walking the SDW and from which direction we had come.

We signed in at the bar, taking to care to reserve our places at the first breakfast sitting, which is at 09:00. (There are two sittings because the breakfast room is small. I had tried reserving in advance but was told I couldn’t.)

Following a brief tour, we went up to our room.

It being Tracy’s birthday, I had splashed out on one called Snaggey, which has a super kingsize bed and an ensuite roll top bath. Midweek bed and breakfast cost me £183.

We ran a slow-filling bath and, having soaked away the mud, headed downstairs to the bar for a drink, ahead of dinner in the restaurant.

I enjoyed a pint of Amberley Ale, brewed by the Langham Brewery in nearby Lodsworth, while Tracy had her usual cider.

This is a prosperous part of the world, so the air was full of cut-glass, public school accents, emerging from a predominantly elderly clientele.

Dinner was very good indeed. I had a starter of mini haggis, neeps and tatties, in honour of Burns Night, followed by venison with sprout tops, all rounded off by apple and plum crumble with custard.

Next morning we made our way down to the breakfast room at 09:00 precisely, only to find that our booking hadn’t been received by the breakfast team. Fortunately, they squeezed us in anyway. Breakfast was delicious and we were allowed to put extra coffee in our flasks for later.

I tried to work out the relationship of the four women of a certain age sitting at the adjacent table: two elderly mothers and their two middle-aged daughters maybe?

Day 2: Amberley to Washington

We were under way by 10:00 in glorious winter sunshine, making our way back up Mill Lane towards a beautiful house called Highdown, which I remembered from previous walks in the vicinity.

Several Roman burial sites were said to have been uncovered when it was built a century or more ago.

Further up Amberley Mount, which we were now ascending, there is evidence of late Bronze Age settlement: two large circular huts have been excavated here.

There are also several more tumuli and, a little further on, earthworks known as Rackham Banks – a cross dyke adjacent to another small late Bronze Age settlement.

Our attention was drawn by the glorious view across the Arun Valley beneath us, revealing further flooding along the course of the River. We tried to spot the Black Horse from a distance.

Suddenly a glider whooshed past us, the first of several passes during the next hour.

We stopped to look down on Parham House. The Estate was owned by the Monastery of Westminster, but Henry VIII bestowed it upon one Robert Palmer of Henfield, and the Palmer family built the house in the 1570s.

It was bought by Sir Thomas Bishopp in 1601 and the Bishopp family retained it until 1922. Then it was purchased by the same family that owns the Cowdray Estate. Now it is owned and run by a charitable trust chaired by Lady Emma Barnard, the Lord Lieutenant of West Sussex, who inherited the property and still lives there.

As the day warmed, I borrowed some of Tracy’s sun cream, which has never before been applied on a January day in England!

We stopped for coffee in a small wooded copse, watching a young buzzard hunt slightly further down the slope.

Emerging from the shade, we began to encounter a steady stream of dog walkers, courtesy of the car park at Kithurst Hill. Further on, near Chantry Lane, we enjoyed a small pond, glittering in the sunlight.

Just beyond, two model plane enthusiasts were attempting a launch…and were ultimately successful.

We passed a herd of cows behind a fence, waiting patiently for their lunch and, shortly afterwards, I held open a gate for a horse and its rider to pass through.

The horse seemed to be heading straight for my face until the rider wrenched the head round with his reins. They descended slowly down the hill, accompanied by a dog.

We reached a fingerpost informing us that we had completed 52 miles of the SDW and had just 47 left to go.

We could just see lines of wind turbines – presumably one end of the Rampion offshore wind farm – and a radio mast over by Worthing.

Rampion has 116 turbines, each hub 80m high; each blade with a 112m diameter. It should generate sufficient electricity to power some 350,000 homes.

At Barnsfarm Hill there are two options, both marked as the South Downs Way. One route turns off left, steeply downhill, before curving round into the centre of Washington and over the A24 near St Mary’s Church.

The more direct route heads straight on, down Highden Hill, passing another, closer radio mast. As we belatedly discovered, there is no bridge across the A24 at this point, forcing one to take one’s life in one’s hands.

The Guide says:

‘The A24 crossing is extremely busy, so the South Downs Way is now officially only signed following the old A24 route north to the village of Washington.’

We don’t recall it signed that way in the direction we were walking. Both options seemed equally ‘official’.

Having made it across in one piece, we stopped beside the SDW signpost on the other side. Tracy lost her footing on the lip of a deep pothole and, unable to resist the weight of her backpack, toppled over before I could catch her.

Fortunately, there was no serious damage, except to her pride! We were only 100m from the bus stop, which sits on a slip road called Washington Bostall. It was roughly 13:00.

We caught the bus to Horsham and, from there, a train up to Clapham Junction.

It had been a beautiful day and, overall, a memorable expedition.

TD

February 2025

Leave a comment