This family history post explores the life of Edmund Dracup (1858-1914), a lifelong inhabitant of Bedford, whose descendants spread the Dracup name into Kent and Gloucestershire.

Edmund made a valiant effort to better himself, initially as a teacher and later by converting himself from a printer and compositor into a local journalist. He had a passion for cricket, but was far better at writing about the game than playing it!

He married Louisa Dennis, a nursemaid from Riseley, some miles north of Bedford. They were both shoemakers’ children. She devoted herself to Methodism and temperance, dying a centenarian some 40 years after her husband and outliving four of her six children.

Immediately before their marriage, she was most probably caring for the young Marconi, briefly resident in Bedford with his mother and brothers when aged 4 to 5. But we only have her word for it.

Although she seemed morally irreproachable, Louisa was some months pregnant when they married, which is entirely out of character. She apparently struggled to survive the birth of her first child. Perhaps it was this experience that led her to embrace religion with such enthusiasm.

They had six children. The three elder sons all became printer/compositors, no doubt owing to their father’s influence, but they did not rise beyond this as he had done.

Edmund died aged 55, a victim of the consumption that killed his father, and most probably his grandfather, before him.

Aside from a brief excursion to Lancashire, the eldest son, Edmund Dennis, also remained in Bedford. He was the longstanding secretary of the Bedford Typographical Association, the printers’ trade union. His politics may have conflicted with those of his father.

The second son, Horace Edgar, was in his youth a more talented sportsman than his father. Following his marriage, he moved to Cheshire – and briefly to Leicester for a short-lived change of career – before establishing the Dracup name in Maidstone, Kent, where some of his descendants still live.

The third son, Willis Jesse, returned from the Great War to find his wife living with another man, who had probably fathered his second son. He divorced and remarried, eventually returning to Bedford with his second wife and youngest son, a prominent bird fancier.

His eldest son, Willis Jesse junior, initially fell foul of the law. He followed his mother, stepfather and middle brother to Gloucestershire. Here, while working as a chimney sweep, he was responsible for establishing the Dracups in Yate and Thornbury, where so many of his descendants still live today. Tragically, three of his grandchildren – Margaret Elizabeth (4), Angela (3), and Carol Ann (3) – perished in a house fire.

Edmund’s eldest daughter, Louisa Ellen (Nellie), followed her mother’s lead. But she was also a talented musician, playing violin and cello and performing locally. She never married and, in later life, devoted herself to caring for her mother.

His second daughter Charlotte Rose Melinda (Lottie) began in much the same mould, but escaped through marriage, moving to Hemsby, Cheshire. Sadly, she was killed in a road accident, witnessed by her 10 year-old daughter. Her husband received £700 compensation and remarried soon afterwards.

Finally, the youngest son Alfred James fell under his mother’s influence, rather than his ailing father’s. He became a clerk in the Ministry of Labour, but a promising career was cut short as he became the fourth generation to succumb to consumption.

Their story runs parallel to that of my direct Dracup ancestors, their cousins, who were also resident in Bedford at this time.

Immediate antecedents

Edmund was the eldest son of Jonathan Dracup (1832-1878), one of three brothers who ventured south from Great Horton, Yorkshire, in the 1850s, in search of wider opportunities.

Jonathan and his younger brother Eli (1837-1928) settled in Bedford having spent some years in Wickham Market, Suffolk. Jonathan arrived first, most probably in 1864.

Shortly afterwards, he and his wife Mary (nee Mitchell) lost two infant daughters – Laura Helena in 1865 and Priscilla in 1867. Mary herself died on October 16, 1875, at the age of just 42.

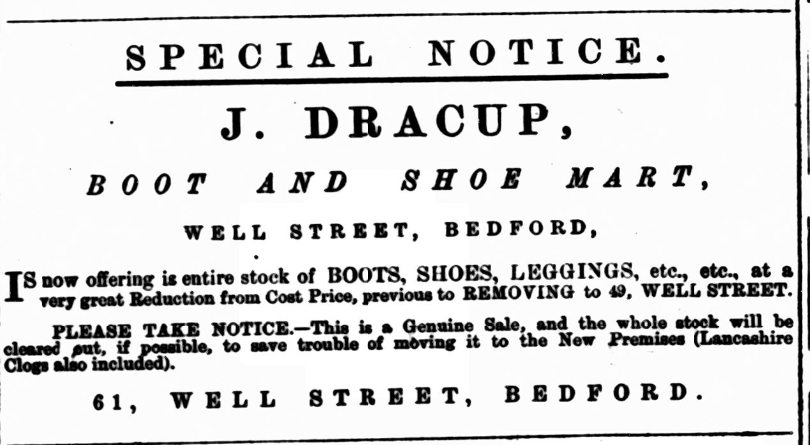

By 1871, Jonathan was a dealer in boots and shoes, based at 61 Well Street (in what is now Midland Road).

He also had literary pretensions. An advertisement carried in the Bedford Record in June 1877 includes a poem – of sorts:

‘Note the fact before you start

If good boots you really seek

Off to Dracup’s cheap shoe mart

Number sixty-one Well Street.

Boots for Rinking, Walking too

In such a splendid varied lot.

Boots for Gentry, and also

For the peasant in his cot.

Boots – the Volunteers’ delight

When they foot to foot advance;

Boots for those who want them light,

When they join the merry dance.

Boots, stout-soled and waterproof,

For gents and ladies in wet weather;

Boots for happy lovers bright,

Just about to join together.

Boots for those who rise each day

And off to their labour dash;

Boots for all who can but pay,

Just a little READY CASH.

Now all who health and wealth would save;

Study ere you further seek;

On your minds these lines engrave,

The Goods of Dracups in Well Street.’

This did not have the desired effect. By November 1877 he had to sell his entire stock, before downsizing to smaller premises at 49 Well Street.

Brother Eli and his young family had arrived in Bedford meantime, quite possibly at Jonathan’s request

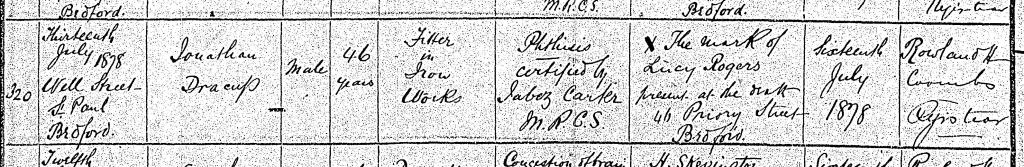

Within eight months, Jonathan was dead from consumption, aged 46, leaving an estate of less than £200 to his five surviving children. The death certificate listed his employment as ‘fitter in an iron works’, suggesting that he had ultimately lost his shoemaker’s business.

I have written already about The Explosive Misfortunes of Emily Dracup, Jonathan’s eldest child, and Edmund’s other siblings.

Emily had married in Bedford in 1876, only to lose her young husband in a gunpowder explosion just a year later. After her father’s death she moved to Portsea on the South coast, accompanied by her baby daughter and two younger brothers, Jessie Lund and Albert Eli. Her sister Rose Melinda also went to Portsea, entering service in a house nearby.

That left Jonathan’s eldest son Edmund the only family member still resident in Bedford, although his Uncle Eli and family were living close by.

Edmund’s youth

Edmund had been born in Wickham Market in April 1858, and baptised there, at All Saints Church, on 25 July.

He appears in the 1861 and 1871 censuses, initially in Wickham Market and then at 61 Well Street.

We know that he attended evening science classes in Bedford – his name is amongst those awarded a certificate for a Class II Physical Geography examination he took in May 1871.

There is a log book surviving from Riseley National School, kept by the school master. It mentions that, in October 1871, Edmund sat an examination to become a pupil teacher there and, from 1872, served in that capacity with the first class.

Riseley was a substantial village in North Bedfordshire, located about nine miles north of Bedford. The Imperial Gazetteer of 1870 estimated the population to be 1,026, spread between 221 houses.

The local manor, Melchburne House, belonged to Lord St John. The Barony of St John of Bledsoe had been created in the Sixteenth Century. The 15th Baron was confusingly named St Andrew Beauchamp St John, and he it was who established Riseley School. He died in 1874 and was succeeded by his son, even more confusingly called St Andrew St John.

There was no school board: the log book shows that the schoolmaster was accountable to the vicar, whose living was in the hands of Lord St John. The vicar at this time was Joseph Johnson Blick (1832-1885). In April 1873, he married Joanna Hills Bostock, a resident of South Hampstead in London, and left the living in 1876.

The schoolmaster was John Pierson (1843-1915), who began at the School as a certificated master in January 1871, continuing until 1887.

Riseley National School was built in Church Lane in 1840. It could initially accommodate up to 135 children and was enlarged in 1872. However, the log book indicates that attendance fluctuated considerably, not least to accommodate the annual harvest.

Edmund was further examined by the Reverend Blick in March 1872 and judged:

‘…to be a little behind in Grammar, but the piece selected was very difficult.’

He was nevertheless promoted to pupil teacher of the 2nd year, moving on to the 3rd year from 1874 and, the 4th year from 1875.

I could not discover whether Edmund commuted to work, most likely by bicycle, or if he lodged for a time in Riseley. There is a reference to him being prevented from attending one day by floods, which may suggest the former.

The pupil teacher concept had been evolved by James Kay-Shuttleworth in the 1830s. It was intended to improve the education of working class children by apprenticing the most able amongst them as assistant teachers.

They would typically begin a five-year programme at the age of 13, be examined annually and paid on a scale according to seniority and experience. Under arrangements introduced in 1846, the pupil teacher was entitled to 90 minutes’ daily instruction from the school master. The pay was £10 per year.

In December 1875, Edmund was absent for a week ‘sitting for a scholarship at Battersea’. This was only weeks after his mother’s death, and it must be a reference to his Queen’s Scholarship examination, success in which would admit him to teacher training college with a £25 grant.

He would begin a two-year course, with three discrete stages: for candidates, scholars and masters respectively. Progression was by means of examination, after which there was a period of teaching practice.

The reference to Battersea shows that Edmund was seeking entrance to St John’s College, the country’s first teacher training college, established there in 1840. It was located in Old Battersea House, in Vicarage Crescent.

In January 1876 there is a final entry in the school log book:

‘The senior P.T [pupil teacher] who is leaving was presented by the scholars with half a sovereign, which they had gathered for him. On Friday he received notice of his success at the late scholarship exam.’

Edmund’s marriage

I could not definitively establish whether Edmund took up his place at St John’s College, but it seems unlikely.

The next two years were particularly eventful for the family.

Edmund’s elder sister Emily married Charles Clarke Paxton, apprentice to a Bedford gunsmith, in July 1876.

Their daughter was born in the final quarter of 1876, so Emily had been some months pregnant at the time.

But then Charles died on 29 August 1877, following an explosion at his workplace, leaving Emily widowed after the briefest of marriages, their child still less than one year old.

And, just eleven months later, their father Jonathan died following the collapse of his boot and shoe business, leaving only a small inheritance.

One imagines that Edmund must have been required at home, expected to support his family, no doubt dismayed that his nascent career had been nipped in the bud.

The precise circumstances surrounding the departure of all his siblings to Portsea are unclear, but Edmund clearly had no intention of accompanying them, seeing his own future in Bedford.

He might have shared their plight, but he chose a different path.

On 17 August 1879, he married Louisa Dennis in St Paul’s Church, Bedford. Both were aged 21. Louisa was from Riseley, so Edmund presumably met her while he was a pupil teacher.

She had been born on 4 September 1857, to James Dennis (1835-70) a shoemaker and Ellen, nee Hall (1837-1919), both born and bred in Riseley. The connection between their parents’ professions may offer a clue as to how they met.

Their first child was born in January 1880, indicating that Louisa was herself some four months pregnant at the time of their marriage.

Although this doesn’t seem particularly unusual for the place and time, it doesn’t quite fit with her later character as a highly religious woman. Was it necessary for the nursemaid to become pregnant to secure the ambitious Edmund? Was he intending to marry her anyway?

Edmund the printer/compositor

By the time of the 1881 Census, Edmund, Louisa and their son Edmund Dennis were living at 11 St Leonards Street, just a few doors down from Uncle Eli and his family at Number 19. St Leonards Street is a cul de sac on the south side of the River Ouse, close to St Johns Station.

Eli was no doubt keeping a benevolent eye on his brother’s eldest son.

Edmund, now 23, was working as a printer/compositor at the offices of the Bedfordshire Standard. One assumes that he had secured this new job shortly before his marriage.

Two further children were born – Horace Edgar in 1882 and Louisa Ellen in 1886 – before he next appeared in the local papers.

In January 1887, he was amongst the attendees at the annual meeting of the Bedford Working Men’s Institute. This had been founded at least a generation beforehand, initially supported through donations from the Duchess of Bedford and local gentry, but subsequently by members’ subscriptions.

In 1887 receipts amounted to £155 and the Institute had a small surplus. During the year the library stock had been replenished and refreshed and now amounted to over 3,000 volumes.

Edmund was also present at the annual meetings in 1888 and 1889.

At about this time, the family moved to 21 Millbrook Road, newly built, just off the Ampthill Road, still quite close to Eli’s house in St Leonard’s Road.

In December 1888, Louisa was briefly mentioned in press reports of an assault, which places the family at this address. A neighbour, Arthur Nice, was accused by his wife Bertha. Louisa was one of the neighbours who interceded.

She stated that, had they not done so, she feared Bertha would have been murdered. Bertha asked for a judicial separation but the magistrate was unwilling to grant this, considering it not to have been an aggravated assault.

Bertha Nice was a 37 year-old schoolmistress. She and Arthur had married in 1876, when he had been a clerk. They separated soon after this incident and, by 1911, Bertha was a headmistress, while Arthur was a homeless gardener living on the streets of Islington.

In September 1889, Edmund was on the jury at an inquest into the death of a child called Mabel Leadbeater, aged nine months, who was scalded to death when she overturned a saucepan of water placed on the fire. The jury returned a verdict of accidental death.

A few months later, he was on the jury at an inquest into the death of Maria Field, a governess and daughter of a prominent Bedford accountant. The verdict was death from natural causes.

In October 1889, Edmund was invited, with other local journalists, to a dinner given by the Mayor of Bedford, Alderman Hawkins JP, for public officials from across the borough. This indicates how he had risen in status.

Other reports from this period show he was a stalwart member of the Conservative Draughts Club and, by 1891, its Honorary Secretary.

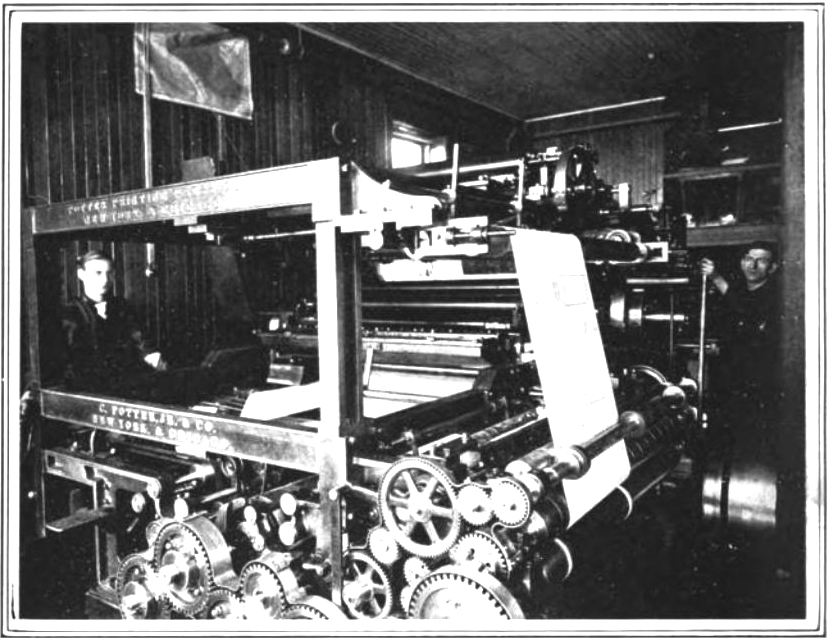

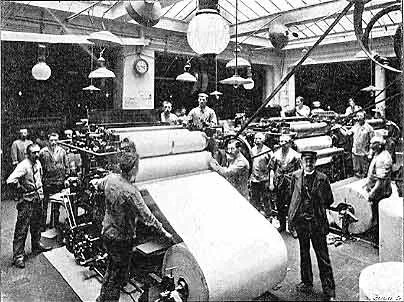

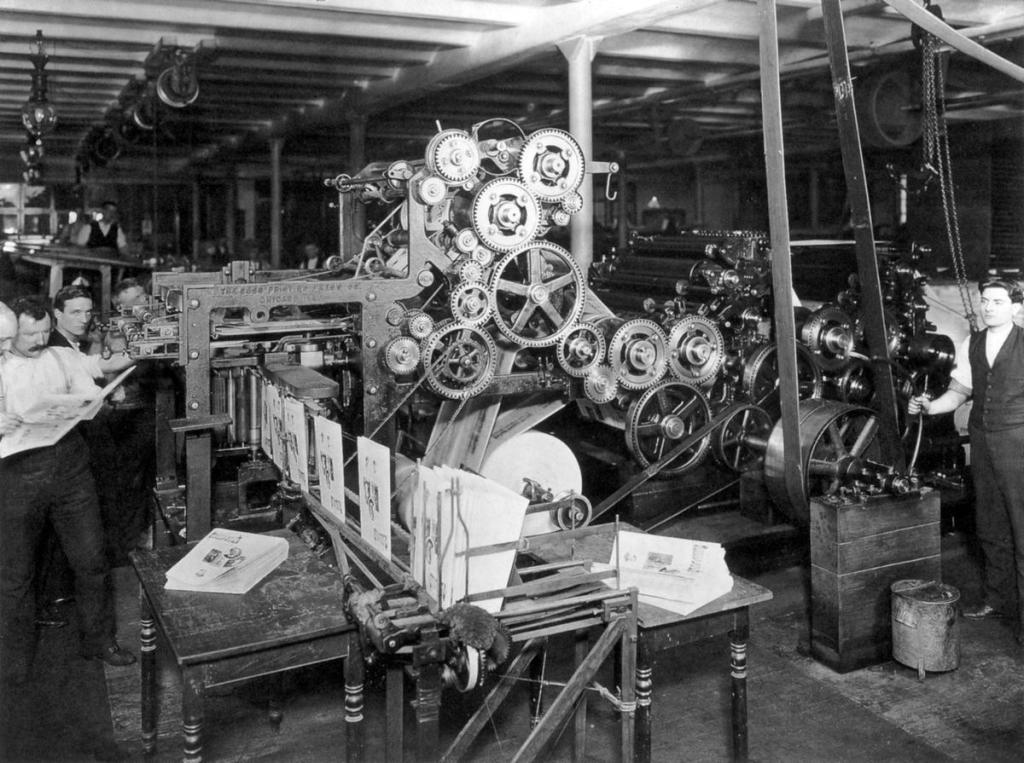

Printing and compositing in the late Nineteenth Century

This was a time of rapid advance in printing technology. In the first half of the century flat bed presses were gradually superseded by those with rotating cylinders. A roll of paper would be attached to the cylinder and pressed on to the bed of type.

By the 1860s, stereotype printing was introduced. A thin metallic plate or stereotype, cast from a mould holding the composed type, would be curved around a rotating cylinder. This sped up the printing process, with the added advantage that it did not wear down the type.

From the 1860s, presses were also introduced that used a ‘web’ or continuous roll of paper, often printing on both sides of the page at great speed. By 1875, the most advanced presses could turn out 14,000 newspapers an hour.

Other machines were developed to fold newspapers, and even the laborious work of the compositor was mechanised.

This glowing description of a ‘composing machine’ patented by Alexander Mackie in 1865 is drawn from ‘A Short History of the Art of Printing in England’ by Arthur C.J. Powell (1877):

‘It consists of two parts; the first, in appearance, resembles a very small cottage pianoforte. It is fitted with keys of ivory and ebony just like its prototype, and is manipulated in a similar manner; where the music would be, is placed the manuscript, and instead of playing a tune, the operator spells out the “copy” letter by letter. By a judicious arrangement of the keys, a whole word can often be spelt at once, just as a chord is struck on the piano.

Every depression of a key produces a perforation in a strip of paper about two inches wide, and of unlimited length, and so quickly is the operation performed, that an average of 16,000 perforations an hour is easily obtained.

When the strip is perforated, it is transferred to the composer, an instrument which looks very like a round iron table with upright projections upon its edge. These projections are boxes in which the types are stored, eight different types being in each box, and on a wheel just underneath them are fixed a number of little platforms, each having a row of holes through which pins may be made to fix.

Much writing and many diagrams would fail to convey an adequate notion of the mechanism of this wonderful machine; it must, therefore, suffice here to say, that driven by steam power, and guided by the perforated strip, in the same manner as the power loom is guided by the jacquard card, the platforms rise to their respective boxes from which the types are extracted by the pins before alluded to. Sometimes a whole word is thus extracted at once, that is to say, when the letters composing it are found in one box.

As the platforms approach a bell-mouthed channel, called the “spout”, a pusher sweeps them off into it and they are thence carried away by a continuous band, and after being turned upon their backs, are finally deposited in a long line, and from time to time are removed by a boy who divides them into lines of proper measure, and justifies them, ie properly spaces them out. With this machine, 15,000 types an hour can be set up, and one machine will do for any sized type from pica to nonpareil.’

By 1886, the linotype had been invented, which enabled text to be selected using a keyboard. The machine drew together a line of letter moulds, over which lead was poured to create a line of type. This enabled a compositor to generate some 6,000 characters per hour.

Printers and compositors enjoyed comparatively high social status and were relatively affluent. They needed a good education to compose type quickly and accurately, were literate and often well-read. They also needed manual dexterity and an understanding of design principles. Most compositors served a five to seven-year apprenticeship before they could qualify as printers.

But a printer’s work was often difficult and stressful, imposing a heavy workload and tight deadlines. It demanded long hours, often spent in poorly ventilated premises.

Though printers were comparatively healthy, certain types of ill health were common. This is Dickens, writing about London printers in 1864:

‘Of printers, the mortality is high, mainly for want of space and ventilation in the printing offices, which frequently are old houses ill suited for the work…

…for the common want also of good drainage, and a complete separation of the water-closets from the workrooms; for want of a wholesomely regulated system of overwork and nightwork, and for want of wholesome arrangement for the taking of their meals by the compositors. Consumption is twice as common among London printers as it is among the general male population of London, and the mortality of London printers, between the ages of thirty-five and forty-five, is considerably more than double that of the male agricultural population.’

It was estimated that 70% of English compositors who died in 1870 did so from consumption or other chest diseases, while more than half of the obituaries published by the Scottish Typographical Association cited consumption as a cause of death.

Perhaps this had something to do with the fact that printing and compositing did not demand great physical strength or exertion, so were relatively attractive to potentially consumptive workers, who were then worn down by working long hours in often crowded and unsanitary conditions, or else contaminated each other.

Edmund the local journalist

The 1891 Census found Edmund and Louisa still resident at 21 Millbrook Street, where they were both to spend the rest of their lives.

Edmund, now aged 35, was described as a newspaper reporter, and their three children were now aged 11, 8 and 4 respectively.

How Edmund made the transition from printing the Bedford Standard to writing for it is not recorded.

He seems to have specialised in coverage of local sports fixtures. In June 1893 he turned up at the annual dinner of the Bedford Swifts Football Club, where he responded to the Chairman’s toast to the Press alongside his colleague from the Bedfordshire Times. The Swifts had been founded only three years previously.

In October 1894 he once more served on an inquest jury, this time investigating the death of Edward de Verdon Corcoran, a wine and spirit merchant, who had been thrown from his dog cart as it was crossing a bridge over the railway line. A verdict of accidental death was returned.

In 1895 Edmund’s name appears amongst the nominees of Samuel Howard Whitbread, of the brewing family, a Liberal, as local MP. This seems inconsistent with his previous politics, and employment on a Tory newspaper.

In September of that year Edmund played cricket for a Bedfordshire Standard team, against representatives of the Bedfordshire Times. The Standard won easily, Edmund contributing seven runs, batting at number 4.

In February 1896, the Bedford United Printers Cricket Club was formed:

‘This new Club was successfully launched last Friday evening at a meeting held at the Peacock Inn, Mill Street. Mr E Dracup was voted to the chair, and representatives of several printing establishments in the town were present. As the name implies, the Club is to be confined to the Press and Printing Trades, and as several of the fraternity are possessed of at least a little cricketing talent, the Club has a good prospect before it and should be able to give a good account of itself and to hold its own with the junior clubs of the town and neighbourhood. Mr J W D Harrison (Beds Standard) was elected President; and the proprietors of printing establishments in the town, with Editors and Managers of newspapers, are to be invited to become Vice Presidents…

…It was decided that the Club’s colours should be black and white, which are decidedly appropriate, a jocular member remarking that white paper and black ink are the chief emblems of the printing trades. The minimum subscription is to be 2s 6d for journeymen and 1s for apprentices, and the practice ground will be Bedford Park. The Secretary has already commenced the arrangement of matches, and as the Club will also join the proposed Bedfordshire League, should such be formed, it will have a full season’s cricket.’

In May that year, both Edmund and his eldest son were part of a United Printers’ team that easily beat Kempston, though neither was called upon to bat. One of them did take a catch, however.

In 1897 Edmund joined the Committee. He played several times over the next few years, but usually failed to distinguish himself.

In 1898 Charles Jones was charged with throwing a stone at the glass door of Edmund’s next door neighbour in Millbrook Road, Albert Gleeson. Edmund gave evidence against the boy, who was fined or, if he defaulted, sentenced to 14 days’ with hard labour.

At the United Printers’ annual meeting in February 1900, Edmund was elected captain. He played more regularly, perhaps, but his performances did not improve.

In 1901, he was appointed to the Committee of Bedfordshire County Cricket Club, as a representative of the Bedfordshire League. He was continuously reappointed until 1910.

From 1902, he also served as Honorary Secretary and Treasurer of the United Printers, subsequently leaving playing duties largely to his elder sons.

In August 1903 he gave evidence at an inquest into the death of James Beard, aged 79. A young cyclist called Harold Burton Crisp was pulling an older 12-stone woman in a trailer down Oakley Hill near Clapham, just north of Bedford, when he collided at speed with the victim. Edmund had been cycling himself, to nearby Milton Ernest.

The inquest jury found Crisp culpable; he was arrested and charged with manslaughter. Edmund also gave evidence against him at the subsequent criminal trial, where Crisp was exonerated.

In May 1905, plans for alterations to 21 Millbrook Road were agreed.

In 1908, Edmund was persuaded to retain his role as Hon Secretary and Treasurer of the United Printers, but only on condition that he received some assistance. This arrangement continued in 1909, but he finally gave up the post in 1910, having held it for 12 years.

Local journalism in the late Nineteenth Century

This was the heyday of the local newspaper. Local papers were particularly valued by their working class readership. They were often made available in reading rooms, pubs and working mens’ clubs, as well as to private subscribers. Some copies might be read a dozen times or more.

It was relatively common for printers to transform themselves into journalists and, by so doing, seek to escape their working class origins. But those origins helped them to appreciate what their readership wanted from a local paper, not least the promotion of their town’s local identity and a sense of community.

The coverage of sport had a particular significance in this respect, and it seems this was Edmund’s particular specialism, though he would have been unable to escape more general duties.

The Standard was founded in 1883, so it seems likely that Edmund joined at its inception, initially as a printer. The newspaper company was registered with £2000 of capital distributed in £1 shares. It was a weekly paper with a decidedly Conservative bias, published every Friday, costing one penny.

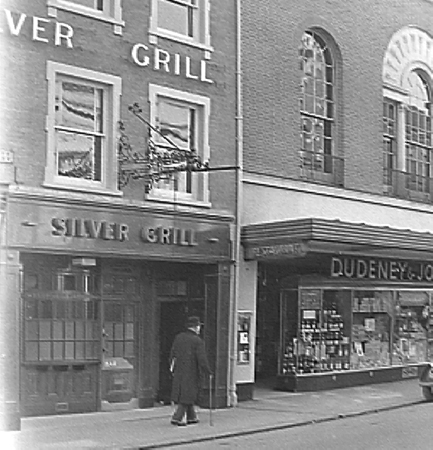

The publisher was Frederick Thomas Howard. He had been born in 1853 and began his career as a printer’s apprentice. By 1891, he and his family were resident at 61 High Street and he described his employment as ‘stationer’. The shop often appeared in the local press, typically as a venue where a local dentist extracted teeth!

The Standard was initially based next-door-but-one, at 65 High Street but, by 1903, the newspaper, printers and stationery shop were all resident at Number 61.

The paper was initially edited by Philip George Skipwith (1824-1909), a barrister. He was succeeded by John William Drinkwater Harrison (1848-1946), a civil engineer and local politician, whose tenure ran from 1896 to 1913. He it was who had been elected President of the United Printers’ Cricket Club.

Charles Bumstead (1864-1908), was latterly the newspaper’s manager. At the time of his funeral, Edmund was one of four reporters employed by the paper.

Edmund’s decline and death

In March 1910 Edmund was presented with a ‘gold albert’ in recognition of his long service for the United Printers.

The 1911 Census indicates that all three elder sons had left home. The only children remaining were his two daughters and youngest son.

It suggests that Edmund was still active as a journalist, but he was coming to the end of his career.

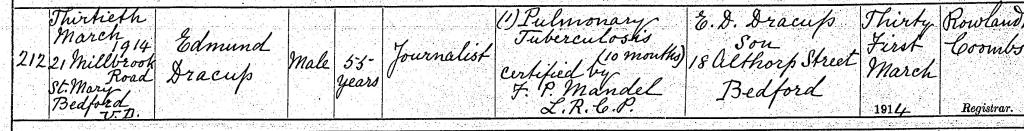

He died on 30 March 1914 and was buried in the Foster Hill Road Cemetery. His death certificate states that the cause was pulmonary tuberculosis, which he had been suffering for ten months. The death was reported by Edmund Dennis, his eldest son.

I can find no reference to his death or funeral in contemporary digitised Bedford papers, though surely the Standard itself must have carried an obituary.

This brief eulogy was published in the Biggleswade Chronicle of 10 April 1914:

‘DEATH OF A WELL-KNOWN JOURNALIST

The funeral took place on Saturday at Bedford amid many manifestations of sympathy and regret of the late Mr Edmund Dracup, a well-known journalist of that town. Deceased was 55 years of age and was for many years in the employ of the “Beds Standard” Company. He was widely known in sporting circles and was an excellent writer on this and other subjects. In former years he played a very prominent part in the local world of cricket. He held the post of hon. secretary of the Beds. Printers Cricket Club at one time, and has also served on the Committee of the Beds County Cricket Club. He has been in failing health for some time.’

Edmund’s estate amounted to £272, a relatively modest sum, not much greater than that left by his father. Probate was awarded, not to one of the family, but to ‘Sidney Charles Moyes, Relieving Officer’.

Moyes had formerly been on the staff of the Bedford Mercury and was a friend of Edmund’s. Now employed as the Relieving Officer for the Bedford Union, he was responsible for alleviating poverty and destitution across the Town.

Why did Edmund select Moyes as his executor rather than his wife or any of his five adult children? It seems that he regarded his three elder sons as now financially independent and, having secured their initial employment, felt no further financial obligation towards them.

He did feel such an obligation towards his wife, unmarried daughters and youngest son, but seemingly didn’t think it was their place to administer his estate, or else didn’t trust them to do so in accordance with his wishes.

An ‘In Memoriam’ notice was published in 1917:

‘DRACUP – In loving memory of our dear husband and father, Edmund Dracup, who died 30th March 1914.

‘Days of sadness still come o’er us

Tears in silence often flow

Ever will our hearts remember

The dear one we lost three years ago’

‘Peace, perfect peace’

- From his loving wife and children.’

Similar notices appeared in both 1919 and 1920.

Edmund Dennis

Youth

Edmund Dennis was born on 19 January 1880.

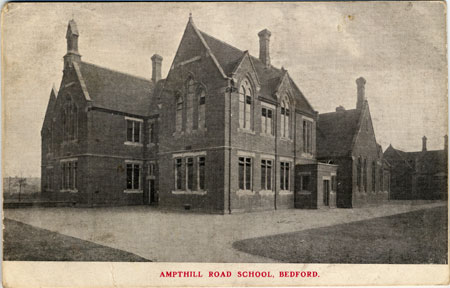

On 1 June 1885, he was admitted to Ampthill Road School, his address given as 28 Gwyn Street, north of the Ouse, at the northwestern limit of the Town.

He was admitted to the Harpur Trust Boys’ Elementary School on 18 January 1887, and completed Standard I. Then, on 31 October 1887, his address now Millbrook Road, he was admitted to Ampthill Road Boys’ School. The record shows he completed Standards V and VI there, departing in January 1893 at the age of 13.

Edmund junior was indirectly the cause of an assault on his mother in 1889. Horace Edgar was also involved, as were turnips!

Contemporary newspaper articles report the trial of George Lepper, an immediate neighbour at 19 Millbrook Street, employed as a bricklayer, who was charged with assaulting Louisa on 3 November 1889:

‘Mr Clare appeared for the prosecution, and in opening the case said he really must in this case ask for something more than the punishment inflicted in trivial cases of assault, because he considered this was a really serious charge.

His client was the wife of Mr Edmund Dracup, and was a fragile and delicate woman in bad health, and just about the very last person upon whom a man ought to lay hands. The defendant appeared to be a violent man, and it seemed to him there was no other term to describe him than as a ruffian. The circumstances under which the assault arose were these:

Complainant and defendant lived in Millbrook Road, which was one of the new roads along the Ampthill Road. It appeared that Mr Dracup’s boys, with other boys, had been playing in the street together, and as far as he could find, doing no harm to anybody, when the defendant chased the complainant’s two little boys.

Both ran down the passage of their own home; the smallest [sic] of the two being so frightened that he got into an outhouse, the other managed to get into the kitchen where his mother was at work. The defendant, however, did not stop, but went right into the kitchen and drove the little lad into a corner, and began ‘leathering’ him, right and left.

The mother was standing by seeing what took place, and defendant was so violent in his treatment of her boy, absolutely without cause, that she went up for the purpose of rescuing him from the clutches of this violent fellow. Defendant thereupon took hold of her with both hands and forced her backwards. She again returned, and this time the defendant struck her a severe blow in the chest, knocking her into a chair.

What possible excuse could there be for a man to lay hands upon a woman in this way, and he asked them to see that this sort of treatment should not go unpunished. Mrs Dracup was immensely upset, and she had ever since been completely unnerved, and she also told him there had been previously threatening words used to her by defendant.

He then proceeded to call the following evidence:

Mrs Louisa Dracup, living in Millbrook Road, deposed that on Thursday last she was working in the kitchen, when her little boy ran in, followed by defendant. Her little boy ran into the corner, and defendant came in and beat him over his head as hard as he could. Her husband was not at home. She told him that if he did not get out of the house she would summons him. He thereupon used bad language and took hold of her by both shoulders and pushed her back. He continued beating the boy, and she asked him, ‘Do you want to kill him?’ He then struck her in the chest and knocked her on to a chair.

Edmund Dracup, ten years old, son of prosecutrix, deposed that he and another boy were playing with some turnips in a field, and Mr Lepper told them not to play with them. They threw them down and defendant chased them down the passage. His brother ran into the barn, and he ran into the kitchen, and defendant followed him and thrashed him. He saw him strike his mother in the chest and knock her backwards.

In defence, Lepper said last witness was playing with some turnips in front of his house, and when he told him to go away he threw one at him and put his fingers to his nose. He ran after him and corrected him. In support of this he called Charles Smith, who deposed that he saw the boy playing with Mr Lepper’s turnips, and when he told him to go away the boy ‘cheeked’ him.

He was fined £1 0s 6d, including costs, or fourteen days. Paid.’

Note the barrister’s description of Louisa as ‘a fragile and delicate woman in bad health’.

Five years after this incident, Edmund Dennis found himself in trouble again. In June 1895, at the age of 15, he was charged at the Borough Petty Sessions, alongside a companion called Charles Jones, with writing obscene words and drawing obscene figures on the door of Ampthill School.

His father blamed Jones, arguing he was the instigator but, nevertheless, the two boys were jointly fined 2s 6d plus costs of 7s.

Edmund junior seems to have been a proficient footballer. In November 1897, when only 17, he captained a scratch team, ‘Mr E D Dracup’s XI’, which lost to Bushmead Albions 2-3, the game being played on the Duke’s Field.

Marriage and family life

In July 1900, aged 20, he married Elizabeth Sarah Wooding, aged 22, the eldest daughter of William Wooding, a hotel porter. On the face of it, this doesn’t seem a favourable match for the eldest son of upwardly mobile parents.

Shortly afterwards, the pair removed to Darwen in Lancashire, where they were at the time of the 1901 Census, living at 18 Harwood Street. Edmund was employed there as a printer-compositor.

On 3 November 1901, a daughter, Edith Beatrice Dracup, was born at Darwen.

But succeeding children were born in Bedford, suggesting that the period in Darwen was brief: Edward William arrived in April 1904; Elsie Kate in October 1907 and Edna Dorothy in September 1913.

We know that, by 1908 at the latest, Edmund Dennis was employed by the Bedfordshire Times, direct competitor to Edmund’s Standard.

The Bedfordshire Times Publishing Company Ltd. had been formed in 1905. In 1910, the company purchased a factory in Sidney Road to house the Sidney Press, which produced books and pamphlets while the Newspaper was printed at its offices in Mill Street.

The 1911 Census recorded the family living at 13 Sandhurst Place, a semi-detached house only a stones-throw away from Millbrook Road. The three children then born were aged 9, 6 and 3 respectively, while another printer-compositor by the name of Alfred Vince was boarding. Edmund’s employment was described as ‘printer – machine minder’. He was now 31.

In that year, a Beds Times cricket club was formed, with Edmund junior part of the team.

But then, in June 1911, a farewell party was arranged at the Club Room of the Cross Keys, because Edmund – described as a member of the Beds Times Sidney Road printing staff – was leaving to take up a position in Manchester.

The report also mentions that he had been Secretary of the local branch of the Typographical Association (the printers’ trade union) for four or five years.

A precursor of the Association – the Northern Typographical Union – had been formed in 1830. In 1844, it reconstituted itself as the National Typographical Association, but was forced to dissolve in 1848 following a major strike in Edinburgh.

A Provincial Typographical Association was formed in Yorkshire and Lancashire which, in 1877, became the Typographical Association.

The Bedford Branch was established in 1904, so Edmund Dennis may have joined at its inception.

However, it seems he had second thoughts about leaving Bedford, for, in May 1912, he was recorded as playing cricket for the Beds Times against the Beds Standard, a match won by the Times. He played several further fixtures in 1912 and 1913.

In June 1915 there is a reference to Sergeant E D Dracup serving in EARE (the East Anglian Royal Engineers). He would have been 35 at this point. The EARE had their headquarters at Bedford.

The 1918 Electoral Register records him at a different address – 10 Eastville Road, somewhat further down the ladder of side roads leading off the Ampthill Road. It was another semi-detached house.

He was still there at the time of the 1921 Census, now aged 41 and employed as a compositor once more, at the Sidney Press in Sidney Road.

During the 1921 Sidney Press and Beds Times staff outing to Dunstable Downs, Edmund junior reprised his cricketing days, appearing in the Sidney Press Team that beat the Times. He was out for a duck.

He managed to score six runs in the 1922 return match, but this time the Beds Times were victorious.

A 1924 report reveals that Edmund was a supporter of the Bedford and District Workers’ Hospital Fund, attending the annual delegates’ meeting. He became a committee member in 1925.

At the inquest into the death of Alfred William Johns of Eastville Road in December 1927, Edmund is mentioned as having been part of a search party formed by neighbours.

He found a torn piece of raincoat on the barbed wire surrounding a pond in Race Meadows, Ampthill Road, and the body was subsequently discovered. A verdict of suicide was returned.

At the fifth annual dinner of the Bedford Branch of the Typographical Association, held at the Silver Grill in March 1930, Edmund was presented with a marble clock to commemorate his 21 years as Secretary. His wife was also presented with ‘a handsome painted china coffee set’.

In 1935, he had a letter printed in the Bedfordshire Times urging all the Town’s master printers to comply with the fair wages clause adopted by the Town Council.

In 1936, at the twelfth annual meeting of the Bedfordshire Times Social Club, he was presented with a watch in recognition of his eight years’ service as joint honorary secretary.

In December 1937, he attended a meeting organised by the Bedford Division Labour Party, confirming his political persuasion.

That month, he was also presented with an engraved gold badge marking his long service as secretary of Bedford Typographical Association:

‘In his reply, Mr Dracup said he much appreciated the honour paid to him. Except for a short break, when he was working away from the town, he had held the office for over twenty-eight years and had seen the membership grow from twelve to over a hundred. It was his greatest ambition to see Bedford one hundred percent organized for the benefit of both employer and employee.’

In March 1939, at a special meeting of the Hospital Fund, Edmund spoke against the means-testing arrangements then in force and proposed an amendment to revise them.

His wife’s death, and afterwards

In his role with the Bedfordshire Times Social Club, Edmund Dennis was invariably organizer of the annual ‘wayzgoose’ for Times and Sidney Press staff. This was a printers’ annual dinner, often combined with an excursion. The derivation of the term is contested.

Unfortunately though, the last event before the Second World War was overshadowed by personal tragedy. In June 1939, local papers reported the sudden death of Edmund’s wife, Elizabeth:

‘Particularly distressing circumstances surrounded the death in the early hours of Sunday morning of Mrs Elizabeth Dracup, of 10 Eastville Road, Bedford. With her husband, Mr E D Dracup of the composing department of the Sidney Press Ltd, she had spent a happy day on the annual outing of the staffs of that firm and of the Bedfordshire Times Publishing Co. Ltd. After the homeward journey, however, just after Mrs Dracup reached the corner of Eastville Road at about 4am on Sunday, she collapsed and died almost immediately. She had walked on ahead with some friends, and her husband came up to find her lying on the pavement.

Mrs Dracup, who was 61, had suffered from bronchial catarrh for some years but she seemed to be in particularly good health throughout Saturday. She was a native of Bedford, being the daughter of Mr and Mrs W Wooding of Bedesman’s Place. One of her main interests in Bedford was the Women’s Co-operative Guild. Her husband is joint hon. secretary of the Bedfordshire Times Social Club (Sidney Press Section) and for thirty years he has been the secretary of the Bedford Branch of the Typographical Association…’

The funeral took place at the Cauldwell Street Methodist Church.

The 1939 Register shows Edmund now living alone at 10 Eastville Road, his employment described as ‘printer, compositor (jobbing)’. He was to remain at this address for the rest of his life.

In April 1946, the Bedford branch of the Typographical Association resumed their annual dinners (postponed during the war years).

On this occasion, Edmund, retiring as honorary secretary after 36 years, was presented with a cheque:

‘In making the presentation to Mr Dracup, on behalf of the branch members and Bedford employers in the printing industry, Mr Riding [General Secretary of the Typographical Association] paid tribute to the painstaking and quiet manner in which he had carried on. Mr Dracup had shown countless acts of kindness and overcome many problems. Mr Dracup had done a wonderful job of work, which, in the speaker’s opinion, would remain unchallenged for many years.’

In April 1947, the Bedfordshire Times featured Edmund in his role as an allotment holder on the Ampthill Road Allotments, where he had cultivated his allotment comprising ‘twenty poles of stubborn land’ for thirty years.

By September 1957, Edmund was ill in Biggleswade Hospital and he died there on 3 October 1957, aged 77. The funeral was conducted at the South End Methodist Church and he was buried alongside his wife in the Foster Hill Road Cemetery on 7 October 1957.

His children

As for his children:

- In the 1921 Census, eldest daughter Edith Beatrice, aged 19, was working as a Mount Maker at a local picture frame manufacturer, Marion and Foulger Ltd. On Boxing Day 1922, she married Ernest James Denton Copperwheat, a shop assistant, at the Cauldwell Street Primitive Methodist Church. In July 1935, Copperwheat died of pneumonia aged only 39, leaving Edith a widow. By 1939, she and her two children were living next door to Edmund at 12 Eastville Road. Edith died in 1989.

- In the 1921 Census, Edmund William, aged 17, was a compositor at the Sidney Press, alongside his father. In 1926, he married Edna May Jones (1902-90) in Prescot, Lancashire. By 1939, he was working as a linotype operator and mechanic in St Helens. He died in 1971.

- In October 1933, daughter Elsie Kate married James Charles Wilcox (1908-87), a capstan lathe hand, of Victoria Road Bedford. They lost their son, Robert Edmund Wilcox, in 1972 when, working as a signal technician, he was struck by a freight train on the main St Pancras line near Ampthill. Elsie died in 1990.

- In July 1938, Edmund’s youngest daughter Edna married Horace William Arthur Wright (1910-73), a motor fitter. Edna died in 1983.

Horace Edgar

Youth

A second son, Horace Edgar, was born on 15 June 1882. On 22 October 1888, aged six, he was admitted to Ampthill Road School. His father gave his address as Cavendish Street, also to the north of the Town.

He completed Standards III to VI before leaving on 14 June 1895, aged 13.

In 1899 and 1900 he also put in a couple of appearances for the United Printers cricket team, generally outperforming his father. At the annual prize-giving in December 1900 he was awarded an umbrella for his batting performances!

By the time of the 1901 Census he was already employed as a journeyman printer.

From 1900 onwards he regularly played football for Britannia Rovers, featuring in midfield. By the end of 1901 he was team captain. In 1902, however, he switched to play for a different team, called St Cuthbert’s Socials, where he was captain for the 1902/03 season, and elected to the Committee in 1904.

He also continued to play cricket for the Printers Club in the summer, being made second team captain in 1902. At the November 1902 Cricket Club concert he performed two mandolin solos. He continued to play creditably for the second team, which won its league in 1904. In 1905 he joined the club’s committee.

Marriage and a brief change of career

In June 1907, aged 25, Horace married Emma Mabel Bourne, a year his senior. She was the daughter of Richard William Bourne, a land agent and surveyors’ clerk, lately resident in Thornton Heath, near Croydon, and Lucy Patience Spearman nee Saunders.

In 1901, she had been living with her married sister, Florence Seymore, a hairdresser’s wife, at 50, The Grove, in East Bedford. It was a comparatively handsome residence, called Norfolk Cottage, where the family employed a male servant.

The wedding took place at All Saints Church in Upper Norwood. The record describes Horace as a printer, then resident at 105 Stockport Road, Hyde in Cheshire, so he must have departed Bedford at some point between 1905 and 1907.

The 1908 Electoral Register places him at this address though, by 1909, he had moved to 46 Green Street, and in 1910 to 29 Mottram Road, both in Hyde.

A son, also called Horace Edgar, was born on 19 October 1909. The 1911 Census places the young family still at 29 Mottram Road. Horace senior was described as a compositor.

But, confusingly, a 1911 Wright’s Directory for Leicester locates him at 184 Belgrave Gate in that City, describing him as a Draper and Haberdasher.

There was definitely a man of this name at this address, since the Leicester Daily Post of 14 September 1911 reported:

‘The cause of a fire in Belgrave Gate, yesterday morning, was unusual in that although a child was playing with a match yet the conflagration itself was caused by the attempt of the mother to avert the risk of fire.

At 1.35 a telephone message was received by the Fire Brigade that a fire was in progress at the premises of Mr H E Dracup, a draper in Belgrave Gate. They turned out with the motor, under Second Officer Kinder, but on arrival it was found that the fire, which was of small extent, had been extinguished by the neighbours. A pair of window curtains and a Venetian blind were burnt in the upstairs front room, but this was all the damage.

Mrs Dracup stated that her little boy was playing with a match. She went up to him to break the brimstone head off, so that no danger should result. While doing this the head burst into flames, and she dropped it on to the curtain. Immediately all was ablaze, and the brigade were ‘phoned for.’

It must have been a very brief change of career.

By 1913, the family had moved to 8, Railway Bank, Croft Street, back in Hyde, where they remained in 1914.

A daughter, Irene Florence (known as Renee) was born in December 1915, completing the family. By 1918, they were resident at 14 Wood End Lane in Hyde, where they remained until 1920.

Maidstone

An advertisement appeared in The Kent Messenger of 24 July 1920:

‘Small House wanted in Maidstone – Dracup, “Kent Messenger” Maidstone’.

On 14 August, this was clarified to:

‘Small House wanted to rent in Maidstone; or would purchase – Dracup, “Kent Messenger” Maidstone.’

And in 1921 they moved to 5, Pope Street, Maidstone, where they were located at the time of the 1921 Census. Horace, now aged 39, was employed as an overseer in the jobbing letterpress printing department of the Kent Messenger Newspaper and Printer, located at 123 Week Street, Maidstone.

When Renee was baptised, on 10 September 1922, at St Michael’s, Maidstone, the record described Horace simply as ‘printer’.

This photograph of a picnic must date from 1920 or thereabouts. Horace Edgar and Emma Mabel are on the left in the foreground. Behind them are Horace’s mother Louisa, and his sister Louisa Ellen. The second woman near them is possibly his second sister, Charlotte Rose Melinda. Horace’s children, Horace junior and Irene are on the right. I’m not sure of the identity of the three remaining women.

In December 1930, Horace junior and senior acted as officials at the Kent Messenger Old Crocks Reliability Trial, completed by 23 cars, which ran between Maidstone and Ashford.

By then, Horace and Mabel were living at Bedford House, 17, Pine Grove in Maidstone, together with Horace junior. Renee’s whereabouts are unclear.

The 1939 Register showed Horace senior and Emma Mabel still at the same address, and he was still employed as an overseer for letterpress printing at the ‘Kent Messenger’.

Horace senior died in Maidstone on 26 May 1953, aged 70, at the house in Pine Grove. Emmie Mabel died in Oakwood Hospital, Maidstone on 28 March 1966.

As for his children:

- In 1934 Horace junior, aged 24, married Margaret Kelly, a 29 year-old Roman Catholic farmer’s daughter from Roscommon in Ireland. In March 1929, she had been registered as a nurse at the Kent County Mental Hospital in Maidstone. They lived at 61 Monckton’s Avenue. By 1939 Horace had changed employer, now working in the electrical repair trade. Three children were born, in 1934, 1936 and 1943. Horace junior died in January 2001.

- In 1926, Renee was a bridesmaid at the second marriage of her uncle Willis Jesse (see below). She later attended the Military College of Science, temporarily located in Lydd, Kent, at the time of the 1939 Register, when she was part of the 5th Kent Company of the Auxiliary Territorial Service (the ATS). In 1942, she married Ernest Hughes, whose father seems to have been an Oldham lamplighter who married his second wife – Ernest’s mother – bigamously under an assumed name. (He eventually remarried her in 1946 after his first wife’s death). Renee and Ernest had two children before he died in 1962. She died in 2005.

Willis Jesse

Youth and first marriage

Edmund and Louisa’s third son, Willis Jesse, was born on 2 June 1891.

He joined Ampthill Road Boys’ School in October 1897, completing Standard VII in 1904. He left on 13 February 1905, aged 13, going directly into the Bedfordshire Times printing office.

In January 1910, aged 18, he married Jane Hickman, daughter of Joseph Thomas Hickman, a fitter at an engineering works, and Charlotte Elizabeth, nee Northwood. The 1911 Census gives the Hickman family’s home as 7, Coventry Road, Bedford.

Jane was a year older than Willis. A note on her 1901 Census record says ‘paralysed in ankle since childhood’.

Their son, also Willis Jesse (but known as Bill) was born on 27 February 1910, a few weeks after the wedding.

The 1911 Census places them at Littleworth, Wilshampstead. This was a small hamlet located along the Wilstead Road, a couple of miles to the south of Bedford. Willis Jesse was employed as a printer’s compositor.

In 1915 he applied to be a member of the Typographical Association at Redhill in Surrey, suggesting he left Bedford for a period immediately before the outbreak of war. His later divorce papers reveal that the couple was for a time resident at 84, Earlsbrook Road in Redhill.

During the Great War he served with the Royal Army Service Corps. In 1918, he appeared on a list of absent voters from Bedford, the address given being that of his mother – 21 Millbrook Road. His name is annotated: ‘SS/14539: Pte. A.S.C Army Printing Press (AP & SS).

This refers to the Army Printing and Stationery Service.

When he first arrived in France, on 19 August 1915, the APSS had only just established its first printing press at Le Havre. A second press was placed at Boulogne in January 1916 and subsequently a third at Abbeville.

By the end of 1915 the APSS consisted of 17 officers and 400 men – and it was to double again in size by 1917. It was commanded by S G Partridge, a former War Office clerk who, by the end of the War, was a Lieutenant Colonel with a CBE.

Divorce

The 1921 Census recorded Willis senior as a lodger with a family residing at 137 Livingstone Road, Thornton Heath. He was now 30, employed as a Compositor at King and Jarrett, 67 Holland Street, Southwark.

A short article concerning his divorce appeared in the Sunday People of 29 May 1921:

‘‘I’m a striker’’ said Willis Jesse Dracup of Livingstone Road, Thornton Heath, answering a question by his counsel during his suit for a divorce – Justice Horridge: There are a good many strikers just now, unfortunately – Witness: Oh, I mean a blacksmith’s striker. (Laughter.) – The Judge: Ahh, that’s better.

Mr Dracup related how after he joined the Army, he found his wife living with a man named Pike at Coventry Road, Bedford. A decree nisi was pronounced.’

This must have been a short-term departure from his printing career.

In 1921, Willis junior was living with his maternal grandparents at 7, Coventry Road, Bedford.

When his father filed his petition for divorce, Jane was said to be residing at 12 Coventry Road, almost opposite her parents. However, the Census puts that house in the possession of a Henry Holmes and his wife.

Jane Hickman was living under the name Jennie Pike at 24 Grove Place, Bedford. She was married, but not working, and shared the property with a boarder called Florence Williams, employed as a domestic servant.

There is no sign of her son Christopher William, born on Christmas Day 1918, so now two years old.

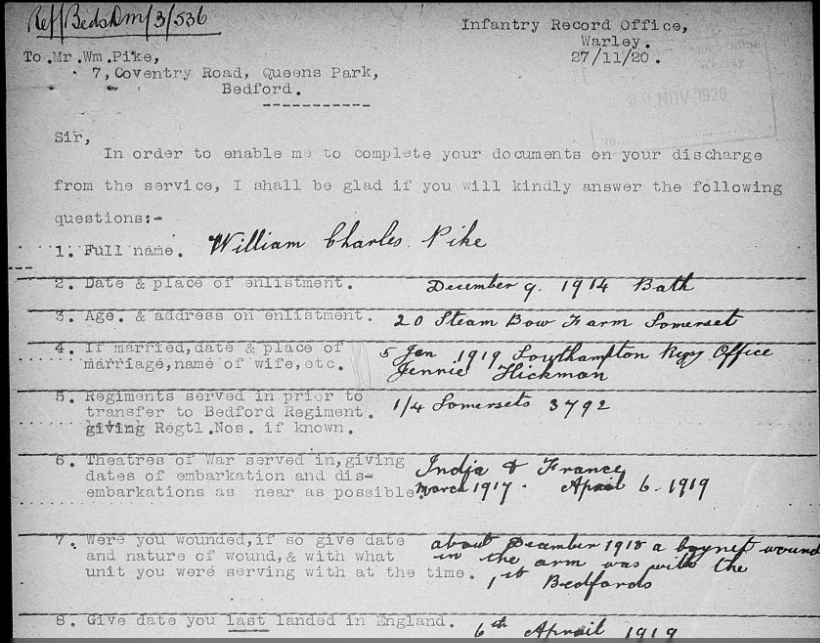

The man named Pike was William Charles Pike. It is quite possible that he was briefly a neighbour in Coventry Road. However, by 1921, he was a patient at Bedford County Hospital. The record gives his employment as farm labourer, of no fixed abode.

It states that he had one child, aged two. This was presumably Christopher William.

The birth certificate, completed by Jane, attributes paternity to Willis senior. But, in his petition for divorce, he clearly states that they have had only one child together – Willis junior.

Christopher’s birth certificate is included with the papers but there is no direct reference to him in the petition.

Instead, that cites repeated adultery by Jane with Pike well after Christopher’s birth, especially from August 1920 to November 1920 at Fritham, near Lyndhurst, in the New Forest, and from November 1920 at 12 Coventry Road.

The former address is very close to where William Pike’s parents were living at the time of the 1921 Census – at Eyeworth, Lyndhurst. Christopher was not with them.

There are war disability records for William Pike, showing that he enlisted and served with the First Battalion of the Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire Regiment from December 1914. His home address was given as Powdermill Cottage, Fretham, near Lyndhurst.

The papers state that he had served in India, Mesopotamia (possibly) and France and that he suffered from malaria and ‘bad feet’. He also claims to have received a bayonet wound in his arm in December 1918.

In 1919 he appears to have signed up to stay with the army until 31st March 1923, under the terms of a Special India Army Order, but must have had second thoughts.

He still seemed to be in the army in September 1920, serving at the School of Cookery at Chiseldon Camp in Wiltshire. He was finally discharged on 20 November 1920, his home address now given as 7 Coventry Road, Bedford.

According to these papers, he claims to have married Jane/Jenny on 5 January 1919 at Southampton Registry Office. This was only a few weeks after Christopher William was born. It was also more than two years before Willis was granted a divorce, so the marriage was either imaginary or bigamous.

Willis was granted a decree nisi on 26 May 1921.

By 1924, Jane/Jenny and William Pike were living in the parish of Thornbury in Gloucestershire, arriving by 1932 in Rounceval Street.

By the time of the 1939 Register, Jane (now Jenny) was living with William Pike at 57 Rounceval Street. She has the correct birthday but is five years younger than her true age. Her son Christopher William was living at the same address and presumably had been with them throughout his childhood.

The divorce had granted custody of his own child – Willis junior – to Willis senior, but the younger man had joined his mother by 1930 at the latest. If he was disowned by his father, that may help to explain his subsequent behaviour.

William Pike died in 1960; Jane in 1968.

Second marriage

Willis senior next appears in a 1925 electoral register, living at 13 Alexandra Road, Upper Norwood, London SE19. Also living at the same property are Henry William Bellchambers and his wife Elizabeth Jane, and it seems that Willis was their lodger.

The Bellchambers family had been living at this same address at the time of the 1921 Census and with them was their daughter Constance Mary Bellchambers, aged 21.

Henry Bellchambers was the Verger of St Stephen’s Church in South Dulwich. His daughter Constance was a Printer’s Assistant at King and Jarrett Printers, Holland Street, Blackfriars – the same employer cited by Willis on his 1921 Census entry.

Willis married Constance on 28 August 1926, at St Stephen’s Church. The marriage record states that he was aged 35, divorced, and working as a compositor. He is said to be living at 19 Colby Road, while Constance was at 13 Alexandra Road. His mother was amongst the witnesses.

There is a description of the wedding in the Crystal Palace District Advertiser of Friday 3 September 1926:

‘On Saturday, at St Stephen’s Church, South Dulwich, a marriage was solemnised by the Rev A E Dalrymple, between Constance Mary Bellchambers, youngest daughter of Mr H W Bellchambers of 13, Alexandra Road Upper Norwood SE, and Mr Willis Jesse Dracup, third son of the late Mr E Dracup and of Mrs Dracup, of Bedford.

The bride, who looked very happy and bright, was wearing a veil with orange blossoms, and was given away by her father. The best man was Mr Robert Grant of Gipsy Hill. The bride’s dress was of white satin and silver lace, trimmed with pearls, and she carried a bouquet of white roses, carnations and white heather.

The bridesmaids were Miss Florence Thyne (oldest friend of the bride), Miss Renee Dracup (niece of the bridegroom) and the Misses Winifred and Freda Crothall (cousins of the bride). The bridesmaids’ dresses were of pale pink crepe de chine and mauve silk net. All carried pale pink carnations.

The bride’s sister was dressed in silver, grey and mauve. The bridegroom’s mother wore a silver grey gaberdine. The bridegroom presented the bridesmaids with very unique black moire bracelets with gold initials.

There was a large attendance of friends and well-wishers at the church and afterwards at the reception at 13 Alexandra Road. The honeymoon is to be spent at Southsea and the bride’s going away dress was a navy blue gaberdine. The happy couple were the recipients of a large number of useful and valuable presents.

A pleasing feature is the interesting fact that the bride’s father has been verger at St Stephen’s Church for 35 years, and is widely known and respected. The bridegroom’s father for many years was editor of the Bedford Times. [He wasn’t]

The bride’s dress was supplied by Madame Silvester, Forest Hill SE. The carriages from the Motor Garage, Victoria Road, Gipsy Hill. The beautiful flowers were privately given.’

Willis Jesse was at the 1930 presentation to his father for 21 years of service to the Typographical Association: the report says he represented the London Society of Compositors, then the printers’ union in Greater London.

A son, Eric Alfred, was born in November 1931.

There are fleeting references to Willis in the early 1930s, while he seems to have been resident in the Croydon area. An article published in July 1936 places him as an employee of the Croydon Times – he was the chief of the stewards who organised a works outing to Southsea (the site of his honeymoon) to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the newspaper.

The 1939 Register shows him living at 112 Anerley Park, close to Penge West Station. It described Willis as a ‘deputy overseer compositor printing trade’.

The family had moved back to Bedford by 1945. The electoral register places them at 29 Spenser Road. By 1957, they were at 9, Norcott Close, but by 1960, they had moved into 21 Millbrook Road with Willis’s sister Louisa Ellen.

Willis died on 22 January 1979, aged 87. Constance also died in January 1979.

Willis Jesse junior

In 1921 Willis junior appeared in the 1921 Census living with his grandparents, Joseph and Elizabeth Hickman, at 7, Coventry Road, Bedford. He continued at school and both his parents were at this point still alive.

On 28 April 1930, he came before the Bedford magistrates, charged with stealing several postal orders worth £2 8s 5d, while briefly employed as a junior porter by Messrs Dusts, Bedford Ltd. back in November 1929. He pleaded guilty.

His present address was given as 20 Salter Street, Berkeley, Gloucestershire. Bill claimed to have been destitute at the time of his crime, and living in a Salvation Army Hostel in Bermondsey. He was bound over for 12 months.

In November 1931, he came before the police court in Thornbury, Gloucestershire, charged with obtaining by false pretences from Mr George Hill of Thornbury, household articles worth £1 1s 6d.

The Police Gazette of 4 November 1931 noted that ‘Willis Dracup, alias Hickman’ was apprehended in Bedford, showing that he occasionally borrowed his first mother’s maiden name.

Mrs Hill had supplied the articles on the understanding that they should be paid for in weekly installments when Bill said he’d just moved in a few doors down. But, she found on making enquiries that this was untrue and he had left the Town.

He again pleaded guilty and was sent to prison for six months with hard labour.

It must have been shortly after his release, on 2 April 1932, that he married Irene Dolbear at St Gregory’s Church, Hayfield, Bristol.

On the marriage record, Bill described his profession as ‘engineer’, residing at Bishopston, Bristol, and his father as ‘William John Dracup’.

This was probably a slip of the pen by the registrar, as Irene’s father is also (correctly) named William John Dolbear, a ‘small farmer’.

The 1933 Electoral register records Bill and Irene living at Church Cottages in Uley, Gloucestershire, next door to his father-in-law.

In June that year, William Dolbear summoned his son-in-law to court at Dursley, charging that he had stolen three fowl valued at 15s. Bill said he had taken them to feed his wife. He was again bound over for 12 months.

By 1939 the family was resident at 23 Rounceval Street in Chipping Sodbury, Bill employed as a centre lathe operator. By 1946, they were at 22 Gaunts Field in Chipping Sodbury.

Between 1932 and 1957, Bill and Irene had seven sons and three daughters.

Disaster struck in December 1961 when three infant daughters of their son Brian Willis Dracup and his wife Pauline, aged 4, 3 and 2, died in a fire while their mother had walked across to borrow soap from her mother-in-law. The family lived in a prefab home in nearby Gaunts Road.

In 1997, the Western Daily Press featured Bill and Kathleen’s 65th Wedding Anniversary. They had a party at their house in Cotswold Road, Chipping Sodbury. At the time, they calculated they had 33 grandchildren, 48 great-grandchildren and one great-great grandchild, plus two more imminent.

Almost all were resident in Chipping Sodbury or nearby Yate, forming the largest concentration of Dracups in England outside Bradford.

The article mentions that Bill had been a chimney sweep for most of his life.

Both Bill and Kathleen died in 2000.

Christopher William

If Christopher William was the offspring of his mother’s initial liaison with Pike, he retained his Dracup surname, in accordance with his birth certificate.

In May 1937, he was charged at the Chipping Sodbury Petty Sessions with obtaining a packet of cigarettes from a slot machine with a metal washer, and was fined £1.

In 1938, he witnessed a fatal accident at nearby Oxbridge, on the main road between Bristol and Chipping Sodbury.

The 1939 Register records his employment as a capstan lathe hand.

In January 1941, he married Kathleen M Hall, the daughter of a mason’s labourer. In 1939, she was employed as a chocolate packer, the family living at Kingswood. They had two sons and a daughter, further contributing to the stock of Gloucestershire Dracups.

Christopher died in June 1986; Kathleen in 2008.

Eric Alfred

Finally, Eric Alfred Dracup, who lived with Willis and Constance in Bedford, was for some years Chairman of the Bedford Cage Bird Society and Treasurer of the Parrot Society from its formation in 1966 to 1981. He was unmarried and died in 1998.

Louisa Ellen

Edmund and Louisa’s eldest daughter, Louisa Ellen (Nellie), was born on 22 November 1886, and baptised on 27 February 1887.

No school records survive, but we know she studied Freehand Drawing and Model Drawing at the Bedford Evening Institute in 1905

In 1908 she, along with her mother and sister, helped organise the annual gathering of the ‘Old folks and widows’ of South End and St Mary’s district. And they seem to have done so for many years subsequently.

In 1909, she was appearing as a soloist with the choir of South End Wesleyan Chapel.

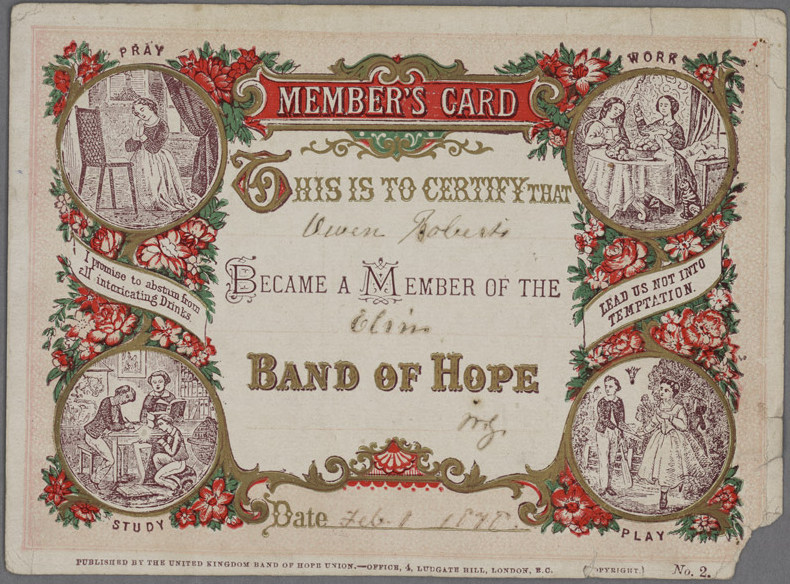

By 1910, she was teaching at the Ampthill Road Wesleyan Church Sunday School and won first prize in the Band of Hope Union’s competitive examination for workers.

The Band of Hope was an organisation, founded in 1847 by the Rev Jabez Tunnicliffe. Its purpose was to teach children the benefits of sobriety and teetotalism. In 1855 the Band of Hope Union was formed, to co-ordinate the activities of local groups.

By 1887 national membership had reached around 1.5 million and, by 1897, reached a peak of some 3.2 million young people. Nationally, membership was estimated at over three million.

The 1911 Census described Nellie as a typist working from home.

By 1921 she was employed as a shorthand typist by Messrs. Marion and Foulger, picture frame manufacturers of London Road, Bedford, where her niece Edith Beatrice was also working. The company had been established by Mr Herbert Charles Rich, and purchased its factory in London Road, Bedford in 1918.

Also in 1921, she several times advertised her services as a private typist in the local press.

She also featured as a member of the Bedfordshire Band of Hope Union Entertainment Party in an entertainment to support the Wesleyan Chapel at Houghton Conquest.

In 1923, she gave violin solos as part of an initiation service for new members at the Bedford Lodge of the Independent Order of Good Templars, another part of the temperance movement.

For many years she was, alongside her mother, one of the principal organisers of the annual Bedford Band of Hope May festival. Local press reports of her involvement continue up to 1934.

By 1930 there is even a reference to ‘Miss Dracup’s Orchestra’ performing in the Wesleyan Chapel at Harrowden. That July, she played cello at a musical service at Cauldwell Street Primitive Methodist Church and in December at Hassett Street Primitive Methodist Chapel.

In October 1931, ‘Miss Dracup’s String Quartet’ gave a concert of Christmas music in the Church Hall at Haynes.

By 1939 she and her mother were living together at 21 Milbrook Road, and she continued to be employed as a typist and clerk. But, in later years, she seems to have devoted herself entirely to caring for her mother.

After her mother’s death, she continued to live alone at 21 Millbrook Road, though from 1960 onwards, she was sharing the house with her brother Willis Jesse, his second wife and youngest son.

She died in 1972.

Charlotte Rose Melinda

On 24 July 1894 Louisa gave birth to a second daughter, christened Charlotte Rose Melinda (Lottie).

She attended Ampthill Infants’ School, where she won a special prize for sewing in 1901. In Standard IV she won a prize for drawing and brushwork

In July 1908 she won first prize of 10s in a children’s poster competition organized by the Bedfordshire Band of Hope Union, on the theme ‘Less Beer – More Boots’.

She also belonged to the choir of South End Wesleyan Church and had roles in the May festivities organized by the Band of Hope Union. In 1908, she played ‘Spring’; in 1909 she was one of three attendants to the Queen of the May; in 1910 she was ‘second fairy’.

The 1911 Census described her employment as ‘day girl (domestic)’, but does not state where she was employed.

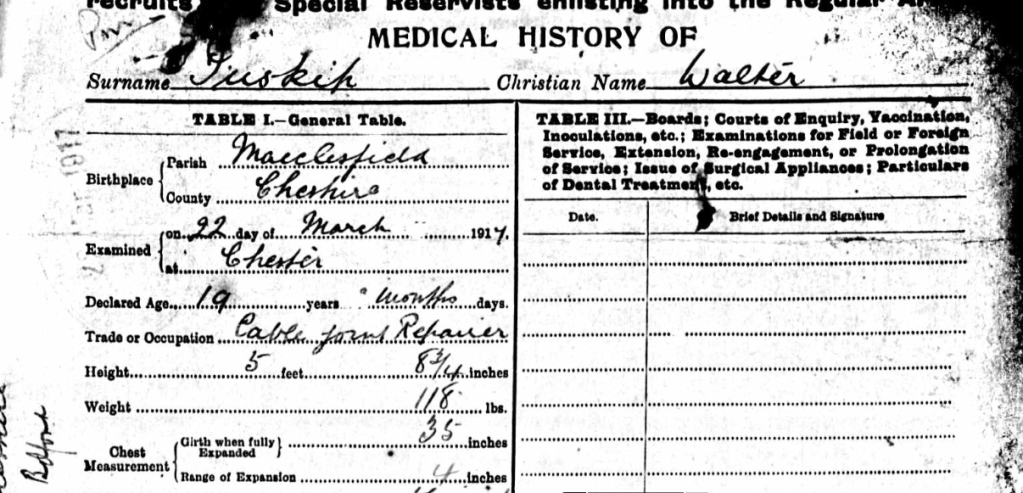

In July 1920 she married Walter Inskip. He had been born in Macclesfield, Cheshire and, when he signed up in December 1915, was resident in Helsby, Cheshire, employed in manufacturing electric cables.

He seems to have served with the Royal Engineers, caught dysentery and been gassed before transferring to a Signals Company. After the War, he was apparently transferred to Bedford as a Corporal Mechanic with the RAF, where he met Charlotte.

After their marriage they moved back to Helsby, where Walter resumed his pre-war job. They had two children – Lawrence, born in 1921 and Vera, born in 1929.

Sadly, on 2 October 1939, Charlotte was killed in a road accident outside her home. The inquest was reported in the Liverpool Echo:

‘How a Helsby woman was knocked down by a motor-cycle as she was about to mount her bicycle near her home was described at a Chester inquest today, on Mrs Charlotte Rose Melinda Inskip, aged 45, of Chester Road.

Mrs Inskip’s 10-years-old daughter Vera, said she had just mounted her own cycle when she heard the noise of brakes. She turned round and saw her mother lying on the side of the road, with her head on the pavement.

The motor-cyclist, Peter Roughsedge, a labourer, of Hazel Avenue, Runcorn, said he was following a lorry, but had no intention of overtaking because the white line was being painted on the middle of the road, and there were red flags along it.

When the lorry swerved out and braked, he applied his own brakes and cut in between the lorry and the pavement, which was the only opening.

A verdict of ‘Misadventure’ was recorded.’

Another article, in the Evening Express has evidence from two different witnesses:

‘…George Henry Simpson of Oldham Street, Warrington, lorry driver, said Mrs Inskip was standing by her bicycle. As he was about to pass, she walked to the offside of the bicycle. He braked, swerved and stopped.

William Fyldes, labourer, of James Street, Widnes, said he was a pillion rider on a motor-cycle driven by William [sic] Roughsedge, of Hazel Avenue, Runcorn. The lorry stopped suddenly and they cut on the inside and struck the woman.’

And a third article from The Observer, adds:

‘…Mr Inskip, giving evidence of identification, said his wife had been a cuyclist for more then 20 years. He last saw her alive just before he left for work after 1pm on the day of the accident, and she then told him she intended to go to Hapsford.

Dr Stephens, House Surgeon at the Royal Infirmary, said Mrs Inskip was unconscious when admitted and was suffering from a fractured skull and a comminuted fracture of the left leg. She died 20 minutes after admission from inter-cranial haemorrhage, consequent upon the fractured skull.’

In February 1940, a case of negligence was heard at Chester Assizes, brought by Walter Inskip against Peter Roughsedge and C J de Burgh of Knutsford Road Warrington (who may have been the owner of the lorry).

A settlement of £700 was agreed, though both defendants denied liability.

One can only imagine what effect this had on young Vera Inskip.

Louisa, her grandmother, attended the funeral, along with Edmund Dennis and his son Edmund William.

Walter Inskip had remarried within the year, uniting in July 1940 with Lizzie Lane, nee Sankey, a widow, district nurse and midwife. He died in 1967, aged 69. She died in 1980.

Alfred James

A fourth and final son, Alfred James, was born to Edmund and Louisa on 3 May 1900. He was admitted to Ampthill Boys’ School on 3 September 1907, having previously attended the Infants’ School.

Unlike his three elder brothers, who were channelled by their father into sporting pursuits and jobs as printers and compositors, Alfred seems to have been left, with his sisters, to the guidance of his mother.

He too had early roles with the South End Wesleyan Band of Hope, in 1910 playing ‘Snowball’ in a musical entertainment called ‘Flora’s Birthday’ which also featured his sisters. He also competed in academic competitions staged by the Band of Hope Union.

He completed Standard VII and left school on 6 November 1913. The record states that he began work immediately in the Office of Bedford’s Director of Education.

On 30 May 1918, shortly after his 18th birthday, he joined the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve. He was stationed at HMS Victory VI, the training establishment located at Crystal Palace, London.

He served there as an Ordinary Seaman until demobilised on 5 February 1919. He is described as 5 feet 6 inches tall, with a 34 inch chest, brown hair, brown eyes, a medium complexion and a scar at the centre of his forehead.

Alfred was still living at home at the time of the 1921 Census, now working as an employment department clerk with the Ministry of Labour. In March 1920, he had appeared in this role at the Bedford Petty Sessions, a witness for the prosecution of a man who obtained ‘out of work donation’ on false pretences.

In 1924, he appeared on the Electoral Register, still living at 21 Millbrook Road with his mother and sister Nellie, but he died soon afterwards, on 4 February 1925, also of consumption, like his father and grandfather before him.

He left effects worth just under £100, his mother acting as executor.

Louisa the Centenarian

Throughout her married life, Louisa was active as a Wesleyan Sunday School teacher at South End Chapel and as a member of the Bedfordshire United Temperance Council.

From 1909 to 1914, she was heavily involved in local Mayday festivities organised by the Band of Hope Union, especially the creation of costumes.

Many of these responsibilities continued after her husband’s death. Indeed, she seemed to devote herself to them more intensively, continuing her involvement well into the 1930s.

In February 1933, at Newtown Methodist Chapel, while attending a Total Abstinence Union Mothers’ Meeting, she was presented with an embroidered tea cosy ‘in appreciation of her many years’ devoted leadership and service in the temperance cause’.

On 4 September 1957, Louisa celebrated her 100th birthday, and appeared in local papers cutting a birthday cake. They mention that she was:

‘…nursemaid to the young Marconi when his family lived for a short time in the town [Bedford]’

Guglielmo Marconi was born in Bologna, Italy in April 1874. He spent two years in Bedford, most probably between 1878 and spring 1880, living with his mother Annie nee Jamieson and brothers at Coleorton Villa, now located at 136 Bromham Road. There is a blue plaque on the building recording this fact.

Louisa was already working as a nursemaid in 1871. Her residence in Bromham Road in that capacity places her geographically close to her future husband.

The newspaper also states that, when her first child was born, her own life was despaired of, but notes that she had already outlived three of her six children. (A fourth – Edmund Dennis – was shortly to predecease her).

I struggle to reconcile her devoutness with her pre-marital pregnancy. Perhaps she considered her own near-fatality as a warning and thereafter devoted herself to worshipping God and denouncing the evils of alcohol.

Is it fanciful to imagine that alcohol had played a part in her own seduction that fateful day in April 1879?

She could not remember the total number of her grandchildren, but estimated she had eight grandchildren, three great-grandchildren and three great-great grandchildren.